poetry

“I share this honor with ancestors and teachers who inspired in me a love of poetry,” the 68-year-old poet said.

Quoth the parrot — “Squawk! Nevermore.”

The stories we tell define history. So who gets the mic in America?

▸

6 min

—

with

Saudade: the untranslatable Portuguese word that names the presence of absence and takes melancholy delight in what’s gone.

We all love the art, but we often forget the difficulty of being an artist. Here are some of the most famous, greatest writers of all time who never could quite make a living doing it.

Get lost in a good book. Time and again, reading has been shown to make us healthier, smarter, and more empathic.

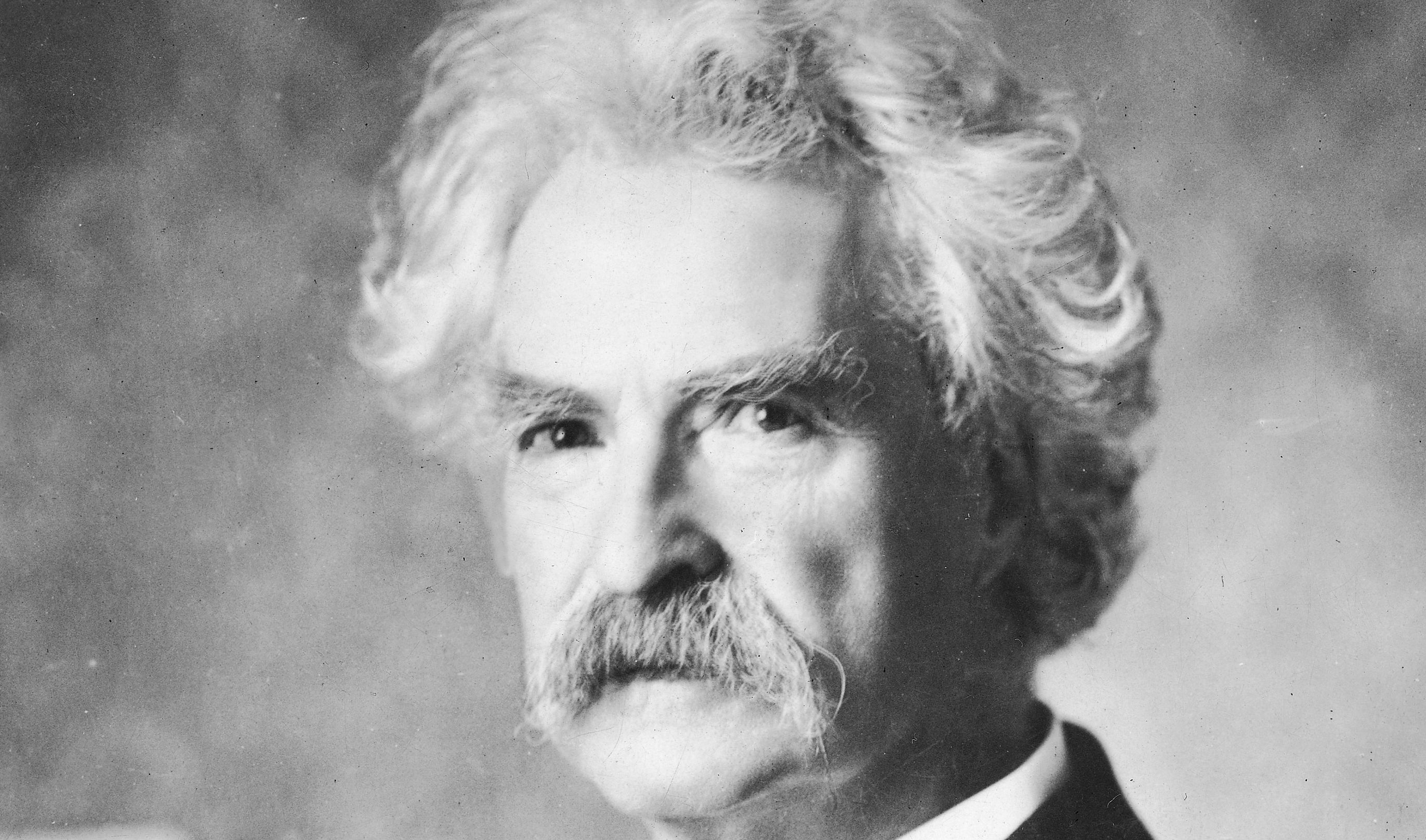

How do you win a Nobel Prize in Literature? First you must get nominated, then it gets hard.

Though the logic of the Nobel committee is pretty easy to glean when it comes to the sciences, in other, less-defined categories, it surprises on a fairly regular basis.

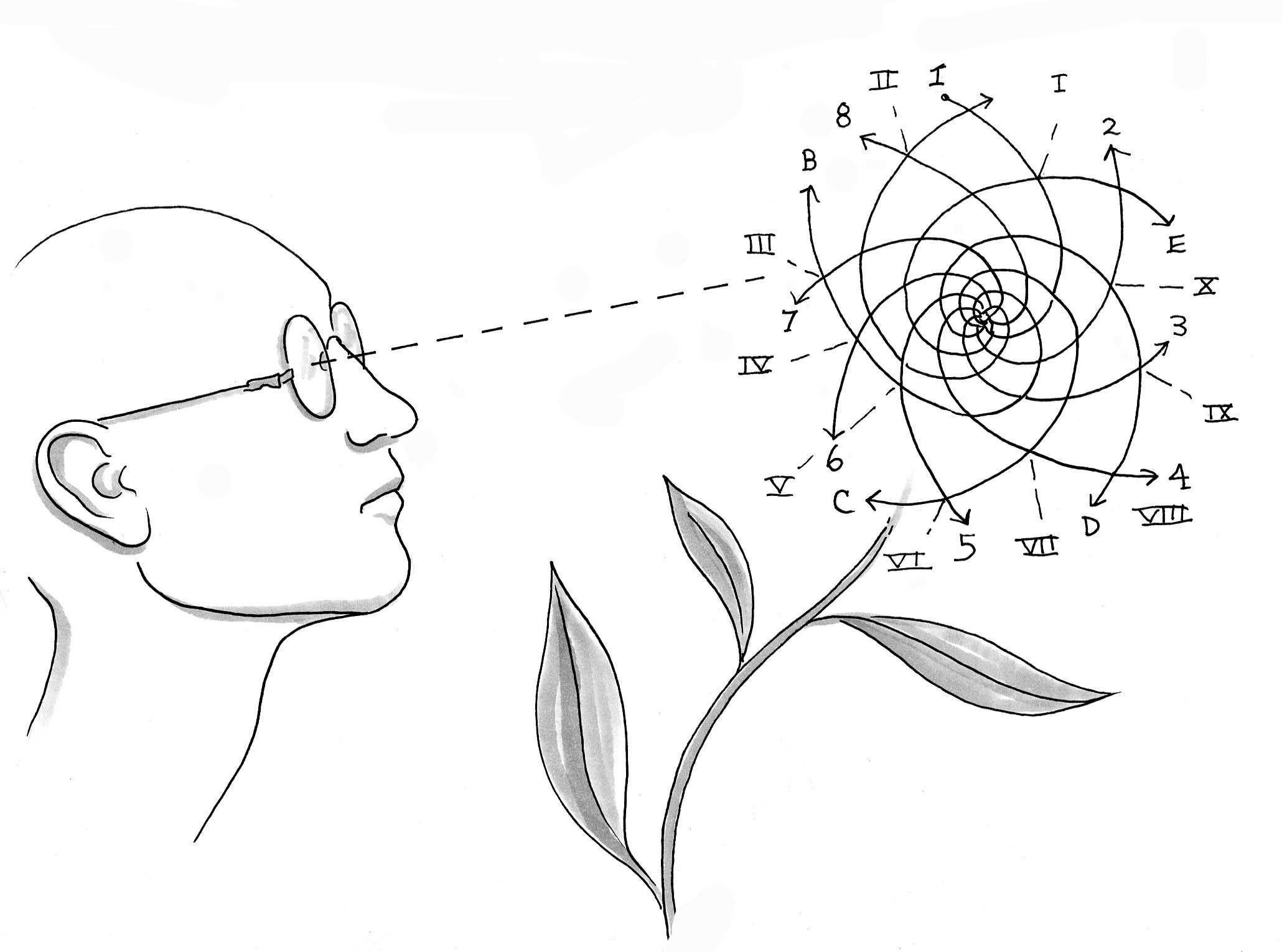

Science’s signature moves share something with good poetry. Good metaphor-making can make geniuses of both kinds. But bad metaphors can mislead whole fields.

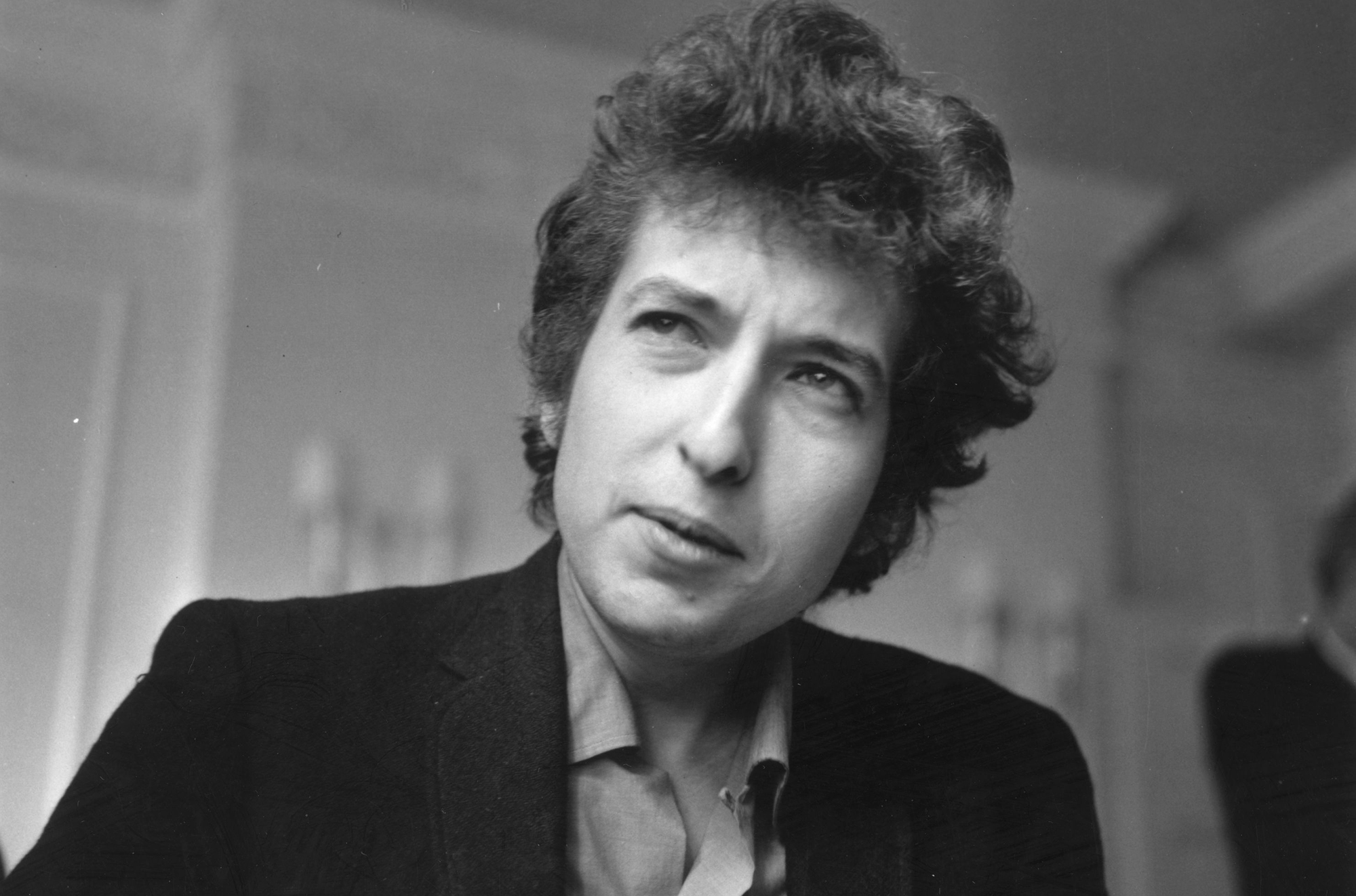

We didn’t mind Maureen Dowd’s dismantling of (whatever remains of) the mythologizing of Dylan as a hero for/of protest. There was a moment in time when Dylan was hero for […]

The poet covers poetry’s dynamics, from graduate to grade school.

▸

8 min

—

with