kant

Think walking is void of philosophy? Nietzsche and Gros are here to say you’re wrong.

Once desire becomes suspect, sex is never far behind.

Are noble 18th-century norms fit for 21st-century life? Especially when, as Yuval Harari says, liberalism’s “factual statements just don’t stand up to rigorous scientific scrutiny.”

Can philosophy give you true understanding about life, the universe, and everything? Sometimes it Kant.

▸

4 min

—

with

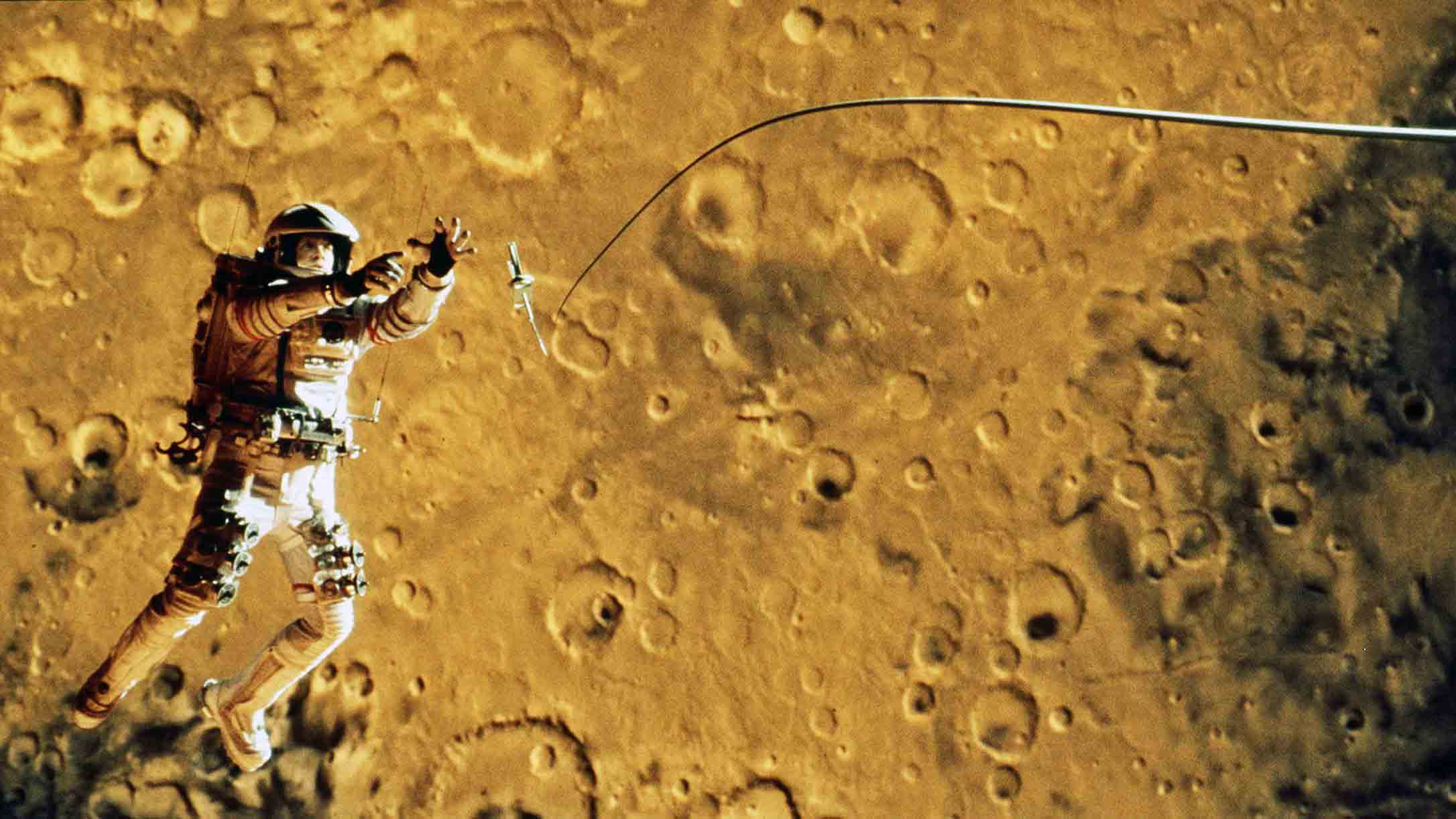

As mankind raises its eyes to Mars and asks, “How do we get there?”, we might need to ask, “Should we go?”. Carl Sagan said we may not be entitled to visit a potentially inhabited planet.