independence

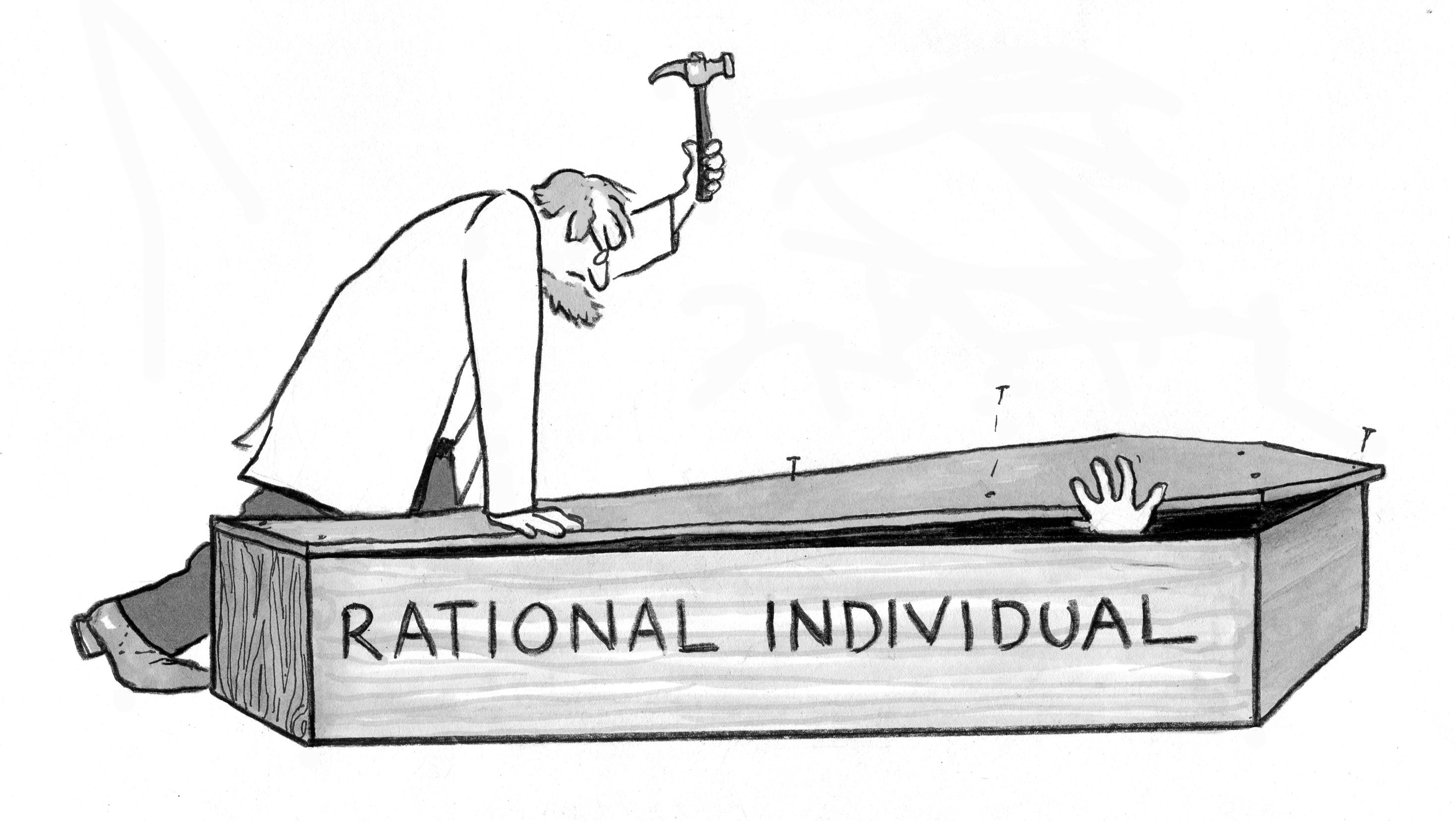

Science (and life) keep hammering nails “into the coffin of the rational individual.” But rationalism and individualism still haunt and systematically mislead—even about where your mind is.

Wake up and smell the independence. Thomas Jefferson urged 18th century Americans to think of themselves not as colonial Englishmen, but as a new culture. To that end, he used architecture to serve as a visual reminder of America’s proud new direction.