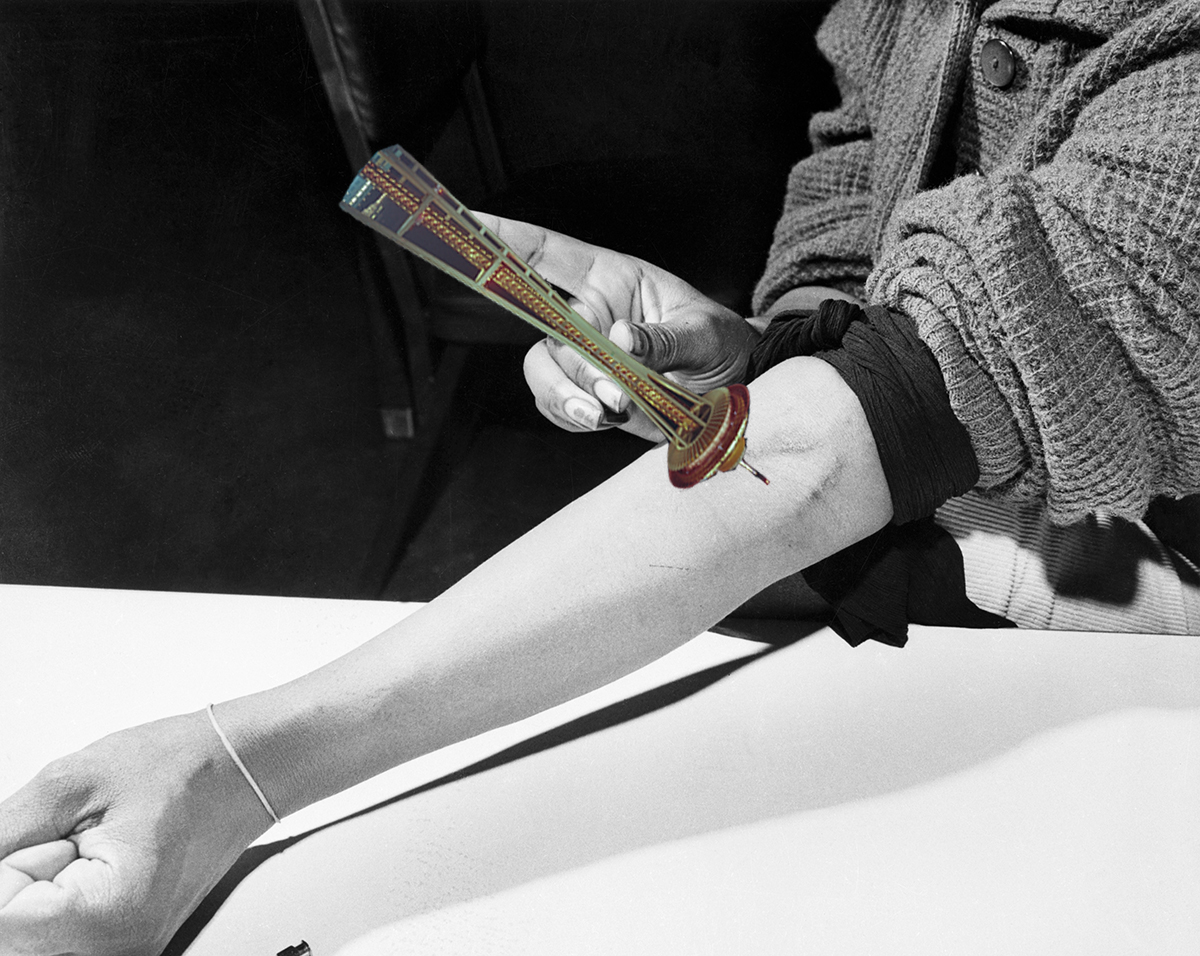

hiv

The CDC’s latest youth risk survey houses some scary numbers but shows that evidence-based sex education is working.

A punishment is handed down for performing shocking research on human embryos.

Facebook’s misinformation isn’t just a threat to democracy. It’s endangering lives.

Chinese scientist He Jiankui edited the genes of two babies to be resistant to HIV, provoking outrage. Now, a new genetic analysis shows why this was reckless.

Recently, “the London patient” became the second person in history to be cured of HIV. Now, “the Düsseldorf patient” appears to be the third, with the possibility of more on the way.

The promising news comes 12 years after the “Berlin patient” became the world’s first person to be cured of the deadly virus.

A Chinese researcher has sparked controversy after claiming to have used gene-editing technology known as CRISPR to help make the world’s first genetically modified babies.

This new pill could make it easier for people to stick to the treatment.

From the depth of the AIDS crisis, a new community discovered itself and defeated victimhood.

▸

8 min

—

with

131,000 people in the United States wait for an organ donation every single day. 10% of them will get one – unless we allow organ donations from drug deaths.

Seattle has a new plan to reduce HIV, drug overdoses, and stray needles: it wants to let addicts shoot heroin and smoke crack legally in monitored spaces.