heroin

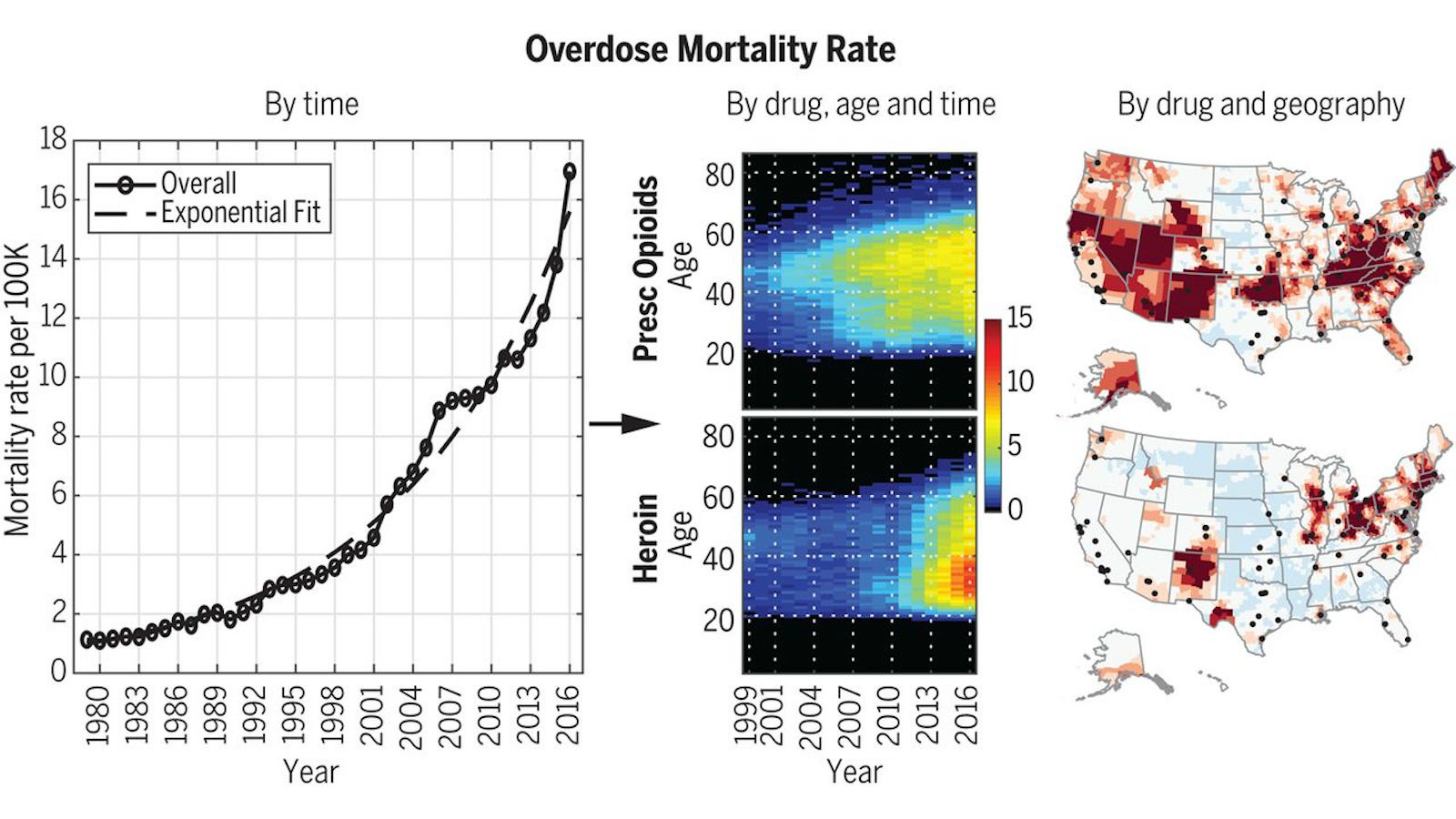

It’s just the current cycle that involves opiates, but methamphetamine, cocaine, and others have caused the trajectory of overdoses to head the same direction

A new report suggests Colorado’s legalization of recreational marijuana might be reducing opioid deaths in the state.

19% of American soldiers returned from Vietnam addicted to heroin. 95% of them recovered without relapse. How?