creativity

Plenty of parents feel guilty about wanting to skip playtime, but there’s no need.

Fun in business is no laughing matter — it can create a golden strategic advantage and bring serious success in the long term.

Meet the scientist mixing mentalism with principles from positive psychology and the science of human potential.

The rise and fall of Josh Harris — the genius who anticipated the digital revolution just a little too soon.

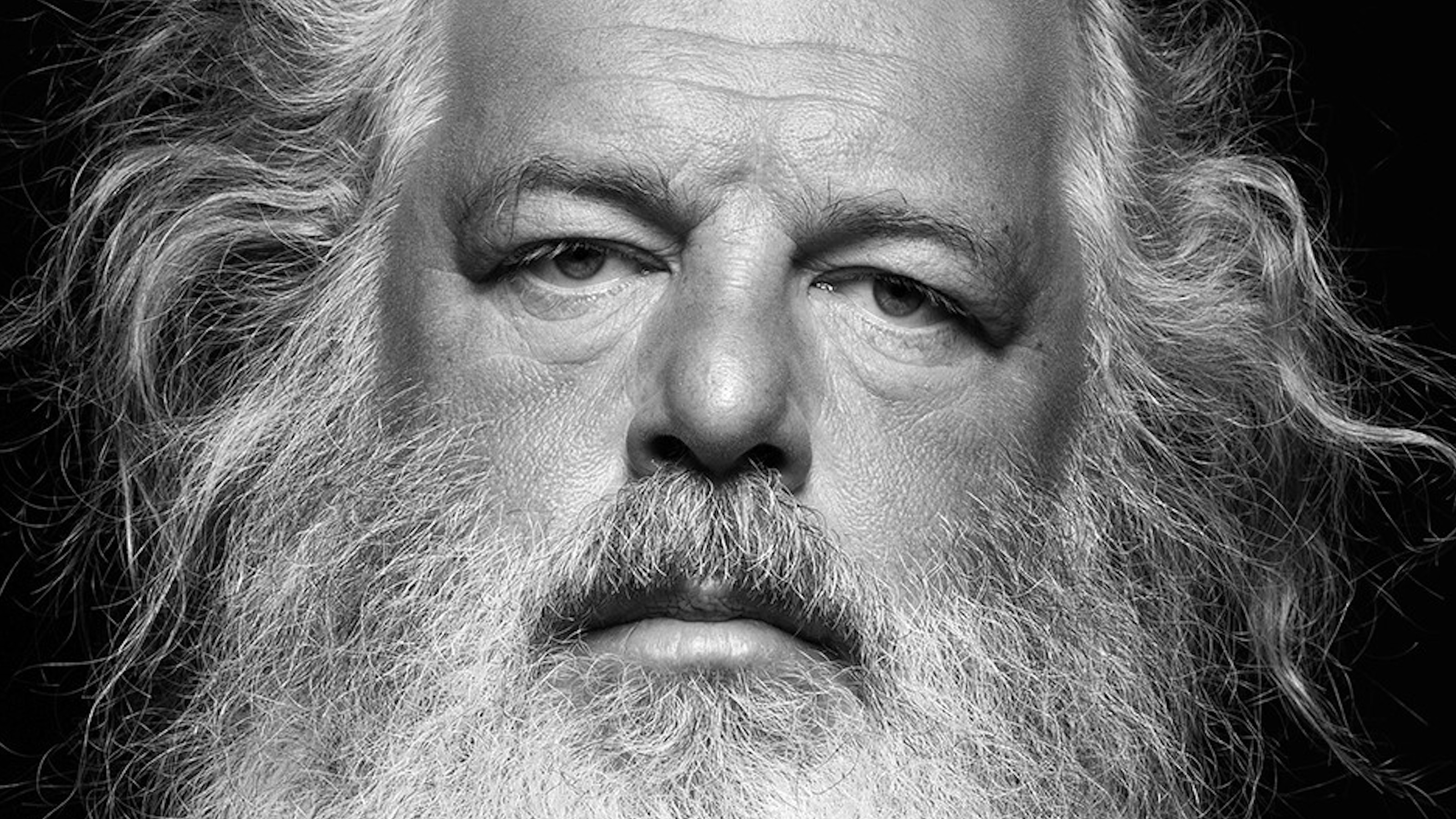

AI researcher and author Ken Stanley wonders how our rear-view perspective on success fits into a serendipitous mode of innovation.

You will need determination, humility, and courage if you are to master anything.

Acclaimed writer Mauro Javier Cárdenas used AI in his latest work to surprising effect.

The transformational change driven by AI will elevate neurodiversity inclusion as an organizational asset, argues Maureen Dunne.

Neuroscience supports the notion that an escape from conventional perspectives can be a gateway to spectacular insights.

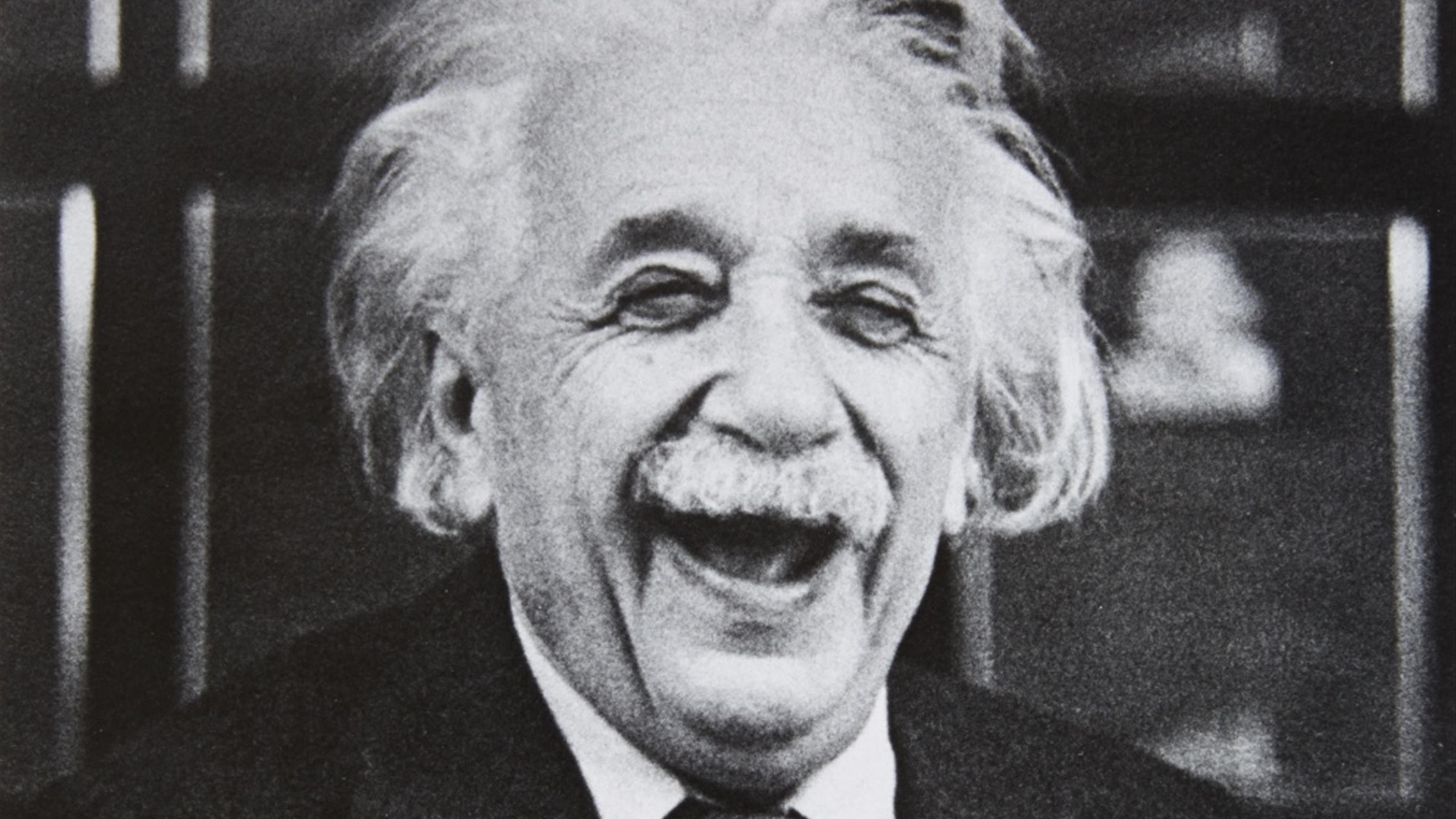

The most celebrated genius in human history didn’t just revolutionize physics, but taught many valuable lessons about living a better life.

Take it from teamwork gurus behind Apple and Star Wars — a new kind of psychological incubator will allow your creativity to flourish.

The great philosopher spent the final portion of his painful life in a vegetative state. Did illness get him there, or was it his own philosophy?

The answer may lie in the power to see far, far beyond yourself.

Scott Dikkers discusses comedy, the creative process, and life lessons learned playing peekaboo.

Your whole body is part of the instrument.

A recently identified stage of sleep common to narcoleptics is a fertile source of creativity.

Thomas Edison was on to something…

Take a hint from Einstein and Mozart — unplug and make peace with some degree of failure.

Forgetting and misremembering are the building blocks of creativity and imagination.

Delay the instant gratification of online knowledge and first seek out the wisdom within yourself.

Try writing a novel without using the letter “e.”

Only humans can voluntarily conjure new objects and events in our minds.

As improving biotech offers us longevity, we can prepare to live much better as we age.

A thesaurus isn’t to find big and fancy words, but a resource to help you find your rhythm.

Can ChatGPT help you power through writer’s block?

Unlock the full potential of your creativity with holistic detachment. This is the way of the editor.

The right questions are those sparked from the joy of discovery.

By developing skills like divergent thinking and collaboration in the workforce, creativity training has the potential to unlock revolutionary ideas.

Creative people are better able to engage brain systems that don’t typically work together.

How do we deal with information overload and unlock creativity? Build a second brain.

▸

6 min

—

with