What exactly makes someone an “artistic genius”?

- We talk a lot about genius. While much has been said about scientific genius, comparatively little is written about artistic genius.

- There's a key difference between talent and genius: The former is about being great within an art form, and the latter is about seeing the world beyond yourself.

- Geniuses are rare, and we ought to use and value the word "talented" more.

We are going through an age of genius – not in that we have lots of them, but in that we are obsessed with them. Books about geniuses fly off the shelves, and the internet drowns in articles about “How to Be a Genius” or “The Habits of Successful Geniuses.” And, mea culpa, we all play our part.

When it comes to the sciences, the word “genius” is fairly well understood. We can understand it in terms of paradigm shifts and the creative destruction that tears down the old ways and reestablishes a better one. But what does it mean to be an artistic genius? What qualities do exceptional musicians, authors, photographers, or filmmakers need?

The problem is that when we talk about the arts, we often use the word “talented.” But “talented” has now become so overused that it’s lost most of its value. Worse than that is to say, “They’re a talented artist” — it feels so limp as to damn a person with faint praise. In response, we have resorted to hyperbole: “They’re a genius,” “a revolutionary,” or a “genre-busting heir to Shakespeare.” The English language has little to offer between the words “talented” and “genius.”

So, what is the difference between the two, and how can we make sense of “geniuses” in the arts?

Express what you can conceive

We can all become talented at something. Talent is defined by hard work, repetition, and deliberate, directed effort. You might be talented at your work because you’ve done so every day for the last ten years. To be talented, then, is to do well at a certain thing. It is no different in the arts. A talented artist is an accomplished — perhaps exceptional — person in their field. They can write, paint, or sing better than most people.

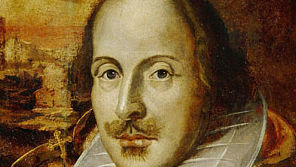

Talent is about the practice of the art itself. It is producing creative work within a certain art form really well. For the essayist William Hazlitt, one example of an artist we might call talented (Hazlitt prefers the term “ordinary” genius) is the poet William Wordsworth. Wordsworth takes what he knows — the feelings, thoughts, and observations of a poet — and turns them into brilliant art. The poet, as Hazlitt wrote, “may repose on his own being, that he may dig out the treasures of thought contained in it, that he may unfold the precious stores of a mind.” In other words, talented artists like Wordsworth work on what they know. They have an experience or story they want to tell, and they tell it well.

The reason this is “ordinary” genius or just talent is that it is egoistic. The talented artist is “self-involved… [and] sits in the center of his own being.” They bring themselves to the world, evoke feelings, or transport us to faraway lands, but with their eyes. They project their experiences onto us. The extent to which we relate to talented artists depends on how far those feelings resonate. Wordsworth wrote about love — as universal a feeling as any — so most people can enjoy his message today. If he wrote about saddle sores while riding on his estate in November, it would resonate less.

The power of conception

The difference between talent and genius is that the artistic genius can express feelings that are beyond their own experiences. They have such an exceptional capacity for empathy and imagination that they can enter into and vividly paint worlds that are foreign to them, or conjure artistic works that are unlike anything ever seen or heard before. For Hazlitt, one man stands out: “Shakespeare (almost alone) seems to be a man of genius, raised above the definition of genius.”

Shakespeare could express the horrors of war, the nadir of grief, and the throes of love in a single play. He could represent the common man and the aristocrat, country life and city life, and England and abroad. As far as we know, he did all this from his relatively unexciting life and a house in Stratford-Upon-Avon. As Hazlitt put it, “He was the Proteus of human intellect.”

Artistic genius is not so much about the art itself or the act of singing, writing, designing, and so on. It’s the ability to see things beyond your corner of the world or things no one else has seen at all. As Susanne Langer wrote, “Talent is a special ability to express what you can conceive, but genius is the power of conception.”

The underrated value of the talented

None of this is to devalue the talented. By Hazlitt’s (and most scholars’) definition, a vanishingly few numbers of people can be geniuses — one an age, perhaps. I doubt anyone reading this is an artistic genius. We ought to reclaim the word “talented” for being the badge of pride that it ought to be. Indeed, Hazlitt even believed that hardworking, resourceful, and diligent “ordinary” geniuses are worth more than an unrestrained, unfiltered genius.

Artists, especially talented artists, are those who put in the hours. They work hard at what they’re doing. As Philip Pullman puts it, “Plumbers don’t get plumber’s block, and doctors don’t get doctor’s block; why should writers be the only profession that gives a special name to the difficulty of working, and then expects sympathy for it?”

Talented people work hard, and that, always and everywhere, deserves praise and respect.