Scientists are still fascinated by Phineas Gage. Here’s why.

- Phineas Gage is considered to be Patient Zero for traumatic brain injury.

- The story of Gage at the time was that his damaged brain rendered him a different, monstrous person. This wasn’t true.

- Recent studies demonstrate that an injured brain can see an increase in connection in areas associated with touch and learning.

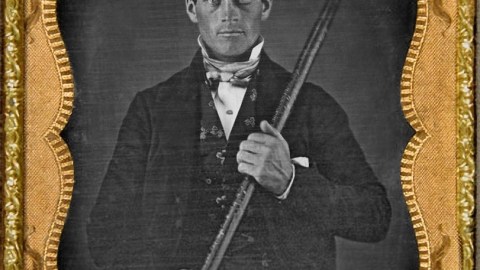

Phineas Gage was a railroad foreman in the 19th century. In 1848, while blasting through rock as part of the construction of the Rutland Railroad line in Vermont, Gage set an explosive — setting explosives in those days included using a tamping iron to pack the material into the rock — and then turned away, his attention temporarily diverted by his men. The explosion went off and the tamping iron drove itself through his jaw, behind his left eye, and out through the top of his skull. He survived.

Why is his survival notable today? Was it because the injury transformed him into a completely different person than the person he was before? J.M. Harlow — the physician who treated Gage in the aftermath of the accident — later described Gage so:—

“He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires. . . . A child in his intellectual capacity and manifestations, he has the animal passions of a strong man. . . His mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was ‘no longer Gage.'”

And though that description made Gage’s case famous, it perhaps did a disservice to how Gage actually responded, which arguably made the particulars of Gage’s case all the more interesting.

As summarized by Slate, regarding the the accident:

“The rod’s momentum threw Gage backward, and he landed hard. Amazingly, he claimed he never lost consciousness. He merely twitched a few times on the ground, and was talking and walking again within minutes. He felt steady enough to climb into an oxcart, and, after someone grabbed the reins and giddy-upped, he sat upright for the entire mile-long trip into Cavendish. At the hotel where he was lodging, he settled into a chair on the porch and chatted with passersby. The first doctor to arrive could see, even from his carriage, a volcano of upturned bone jutting out of Gage’s scalp. Gage greeted the doctor by angling his head and deadpanning, ‘Here’s business enough for you.'”

This was not a child. This was not a man of ‘animal passions.’ This was not a profane man. This was someone who had the presence of mind to make a wry and quiet joke.

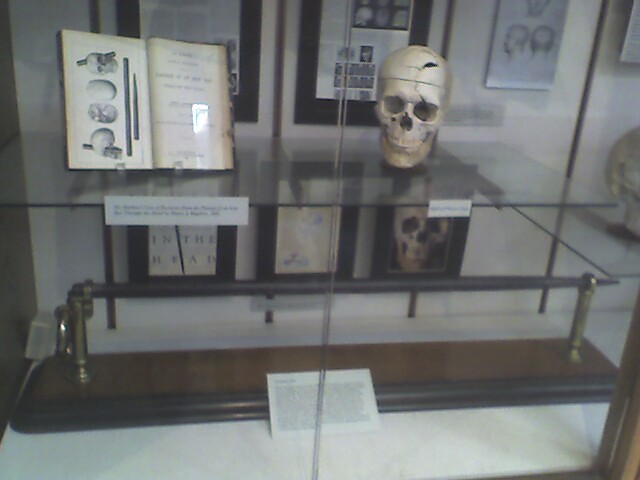

And not only did Gage survive, but his story survived, too. Gage’s case has continued to hold scientific interest and attention over the years, and as the ability to examine the brain has improved, Gage’s case has been returned to as a point of interest again and again. As NPR noted in 2017, one scientist diagrammed Gage’s skull in 1940 in an attempt to trace the path the iron took; a similar process was undertaken in the 1980s using CT scans; a similar process was undertaken once again in the 1990s using 3-D computer modeling; and, in 2012, scientists cross-referenced CT scans with MRI scans of typical brains to show how “the wiring of Gage’s brain could have been affected.”

This repeated returning to the material happened — and has continued to happen — because there have been a few hundred words written about how Phineas Gage changed after the accident.

This also includes a study from 2016 that noted “widespread increases” in connection strength that dwarf both the degree and extent of the damage done to the brain of a rat. There was an increase in connection in areas of the brain associated with — in the human brain, at least — reading comprehension and the storage of memory (what’s known as the Brodmann area and the thalamus caudate), as well as an increase in the region of the brain that responds to touch and muscle input (the S1 region.)

The insight from this study certainly offers up more concrete grounding as to why Gage could survive an accident like the one he did — and how he was able to continue on and work in South America in the years that followed. But that doesn’t mean that the insights from 2016 are the only insights that can be found. There are still several unknowns in neuroscience that researchers tackle and uncover every day, like using light to turn certain neurons in the brain on or off, a study looking at the connection between certain cells in a mouse’s brain with anxiety, and uncovering the flexibility of neurons in the visual cortex processing stimuli — of being able to process the forest and the trees. That level of detail is a world beyond thinking that a different brain means a different personality — and, as time progresses, more research will surely illuminate more details, giving us a more nuanced view of Phineas Gage.