Scientists stumble across new organs in the human head

Credit: Valstar et al., Netherlands Cancer Institute

- Scientists using new scanning technology and hunting for prostate tumors get a surprise.

- Behind the nasopharynx is a set of salivary glands that no one knew about.

- Finding the glands may allow for more complication-free radiation therapies.

The research began about as far away from where it ended up as possible. Doctors were using PSMA PET/CT scans to assess whether patients’ prostate cancer had spread to other parts of their bodies. In addition to being a promising new technology for detecting tumors, PSMA PET/CT scans also happen to be good at imaging salivary glands. Still, radiation oncologist Wouter Vogel and oral and maxillofacial surgeon Matthijs Valstar didn’t know quite what to make of two lit-up areas behind the nasopharynx that looked an awful lot like big, undiscovered salivary glands.

Since finding a whole new organ in the human body at this point is unexpected, to say the least, the researchers re-examined the PSMA PET/CT from all 100 patients in their study, plus two cadavers. Every one of them had the same thing.

Says senior author of the study Vogel, “As far as we knew, the only salivary or mucous glands in the nasopharynx are microscopically small, and up to 1000 are evenly spread out throughout the mucosa. So, imagine our surprise when we found these.”

The study’s lead author Valstar adds, “The two new areas that lit up turned out to have other characteristics of salivary glands as well.”

Vogel and Valstar work for the Netherlands Cancer Institute, specializing in the effects of radiation therapy on the head and neck. Their discovery may help technicians alleviate some common radiation side effects now that they know to avoid the new salivary organs, which they’ve named the “tubarial salivary glands.”

The research is published in Radiotherapy & Oncology.

Cancer researchers discover new salivary glandyoutu.be

PSMA PET/CT is a new combination of PET scans and CT scans that is believed to offer a more reliable means of locating prostate cancer metastasis. A study published last spring suggests it may be the most accurate way to diagnose prostate cancer metastasis than any method previously available.

Prior to PSMA PET/CT, the primary way to look for metastatic prostate cancer was to image the body using x-ray-based CT scans and to perform bone scans, since bone is where prostate cancer often spreads. CT scans, however, often miss small tumors, and bone scans can generate false positives as a result of other damage or abnormalities that have nothing to do with prostate cancer.

PSMA PET/CT scans track the travels of an intravenously administered radioactive glucose tracer throughout the body. For hunting down prostate cancer, this tracer contains a molecule that binds to the PSMA protein that’s present in large amounts in prostate tumors. The molecule is linked to a radioisotope, gallium-68 (Ga-68).

In last spring’s research, PSAM PET/CT was shown to be 27 percent more accurate than previous methods at finding metastases (92 percent accuracy as opposed to 65 percent). In addition, it was found to be much less likely to produce false positives, and it was particularly good at detecting tumors far removed from the prostate.

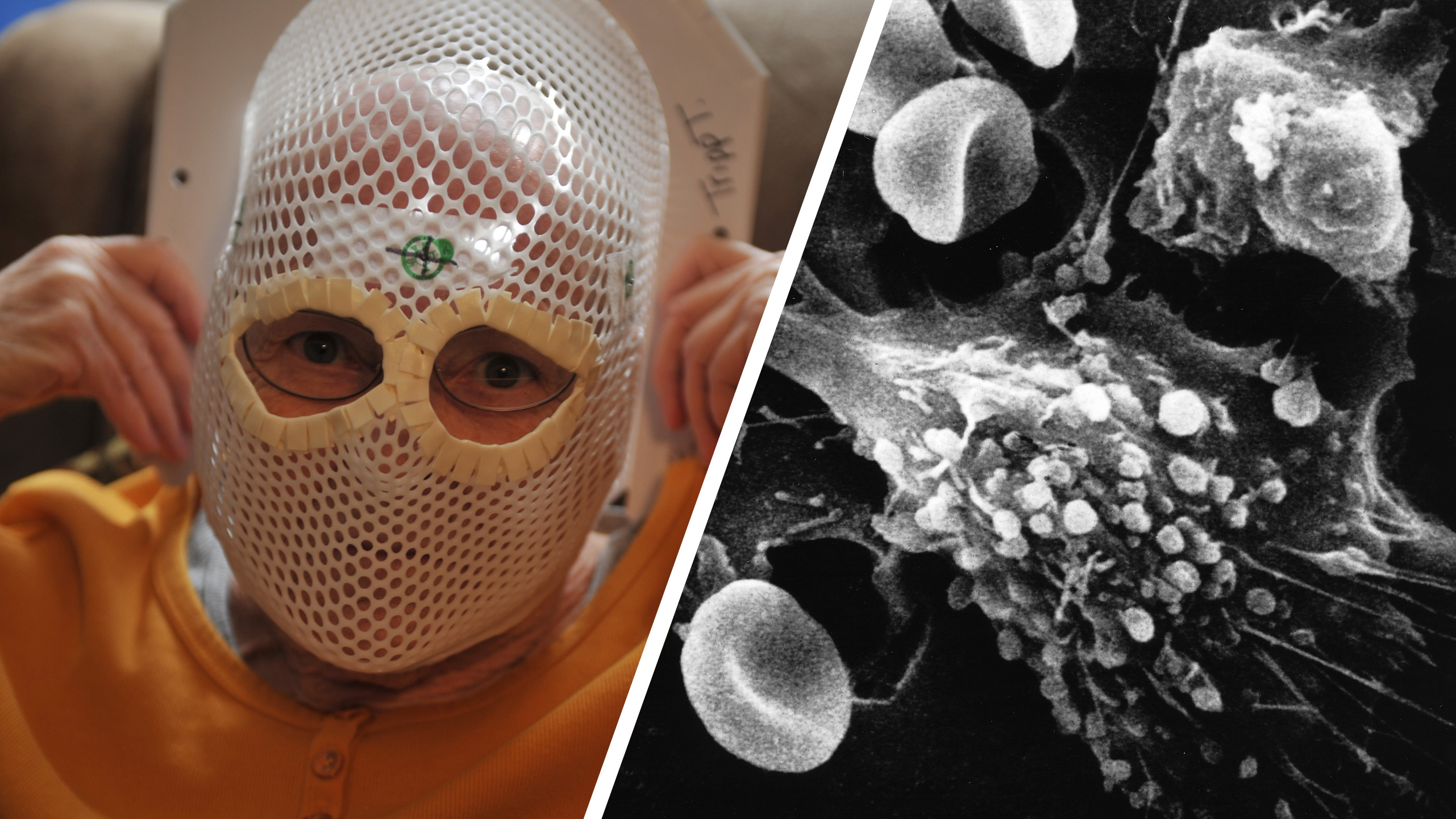

“Radiation therapy can damage the salivary glands,” says Vogel, “which may lead to complications. Patients may have trouble eating, swallowing, or speaking, which can be a real burden.”

The researchers looked back through the cases of 723 patients who had undergone radiation treatment, interested in seeing if inadvertent radiation of the tubarial glands was associated with the complications experienced by the patients. It turned out that this was the case: In cases where more radiation had been delivered to this area, patients did indeed report more in the way of complications of the type one would expect when salivary glands are radiated.

Now that we know the tubarial salivary glands exist, therapists can stay out of their way. Vogel says, “For most patients, it should technically be possible to avoid delivering radiation to this newly discovered location of the salivary gland system in the same way we try to spare known glands.”

He’s hopeful that that things may be about to get at least a bit better for cancer patients: “Our next step is to find out how we can best spare these new glands and in which patients. If we can do this, patients may experience less side effects which will benefit their overall quality of life after treatment.”