The surprise reason sleep-deprivation kills lies in the gut

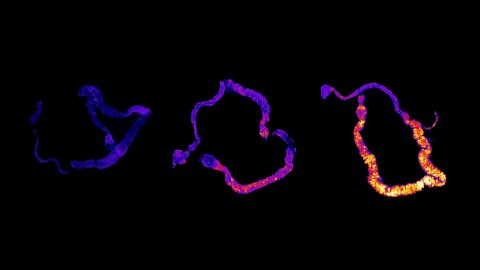

Image source: Vaccaro et al, 2020/Harvard Medical School

- A study provides further confirmation that a prolonged lack of sleep can result in early mortality.

- Surprisingly, the direct cause seems to be a buildup of Reactive Oxygen Species in the gut produced by sleeplessness.

- When the buildup is neutralized, a normal lifespan is restored.

We don’t have to tell you what it feels like when you don’t get enough sleep. A night or two of that can be miserable; long-term sleeplessness is out-and-out debilitating. Though we know from personal experience that we need sleep — our cognitive, metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune functioning depend on it — a lack of it does more than just make you feel like you want to die. It can actually kill you, according to study of rats published in 1989. But why?

A new study answers that question, and in an unexpected way. It appears that the sleeplessness/death connection has nothing to do with the brain or nervous system as many have assumed — it happens in your gut. Equally amazing, the study’s authors were able to reverse the ill effects with antioxidants.

The study, from researchers at Harvard Medical School (HMS), is published in the journal Cell.

Image source: Tomasz Klejdysz/Shutterstock/Big Think

The new research examines the mechanisms at play in sleep-deprived fruit flies and in mice — long-term sleep-deprivation experiments with humans are considered ethically iffy.

What the scientists found is that death from sleep deprivation is always preceded by a buildup of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in the gut. These are not, as their name implies, living organisms. ROS are reactive molecules that are part of the immune system’s response to invading microbes, and recent research suggests they’re paradoxically key players in normal cell signal transduction and cell cycling as well. However, having an excess of ROS leads to oxidative stress, which is linked to “macromolecular damage and is implicated in various disease states such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer, neurodegeneration, and aging.” To prevent this, cellular defenses typically maintain a balance between ROS production and removal.

“We took an unbiased approach and searched throughout the body for indicators of damage from sleep deprivation,” says senior study author Dragana Rogulja, admitting, “We were surprised to find it was the gut that plays a key role in causing death.” The accumulation occurred in both sleep-deprived fruit flies and mice.

“Even more surprising,” Rogulja recalls, “we found that premature death could be prevented. Each morning, we would all gather around to look at the flies, with disbelief to be honest. What we saw is that every time we could neutralize ROS in the gut, we could rescue the flies.” Fruit flies given any of 11 antioxidant compounds — including melatonin, lipoic acid and NAD — that neutralize ROS buildups remained active and lived a normal length of time in spite of sleep deprivation. (The researchers note that these antioxidants did not extend the lifespans of non-sleep deprived control subjects.)

The study’s tests were managed by co-first authors Alexandra Vaccaro and Yosef Kaplan Dor, both research fellows at HMS.

You may wonder how you compel a fruit fly to sleep, or for that matter, how you keep one awake. The researchers ascertained that fruit flies doze off in response to being shaken, and thus were the control subjects induced to snooze in their individual, warmed tubes. Each subject occupied its own 29 °C (84F) tube.

For their sleepless cohort, fruit flies were genetically manipulated to express a heat-sensitive protein in specific neurons. These neurons are known to suppress sleep, and did so — the fruit flies’ activity levels, or lack thereof, were tracked using infrared beams.

Starting at Day 10 of sleep deprivation, fruit flies began dying, with all of them dead by Day 20. Control flies lived up to 40 days.

The scientists sought out markers that would indicate cell damage in their sleepless subjects. They saw no difference in brain tissue and elsewhere between the well-rested and sleep-deprived fruit flies, with the exception of one fruit fly.

However, in the guts of sleep-deprived fruit flies was a massive accumulation of ROS, which peaked around Day 10. Says Vaccaro, “We found that sleep-deprived flies were dying at the same pace, every time, and when we looked at markers of cell damage and death, the one tissue that really stood out was the gut.” She adds, “I remember when we did the first experiment, you could immediately tell under the microscope that there was a striking difference. That almost never happens in lab research.”

The experiments were repeated with mice who were gently kept awake for five days. Again, ROS built up over time in their small and large intestines but nowhere else.

As noted above, the administering of antioxidants alleviated the effect of the ROS buildup. In addition, flies that were modified to overproduce gut antioxidant enzymes were found to be immune to the damaging effects of sleep deprivation.

The research leaves some important questions unanswered. Says Kaplan Dor, “We still don’t know why sleep loss causes ROS accumulation in the gut, and why this is lethal.” He hypothesizes, “Sleep deprivation could directly affect the gut, but the trigger may also originate in the brain. Similarly, death could be due to damage in the gut or because high levels of ROS have systemic effects, or some combination of these.”

The HMS researchers are now investigating the chemical pathways by which sleep-deprivation triggers the ROS buildup, and the means by which the ROS wreak cell havoc.

“We need to understand the biology of how sleep deprivation damages the body so that we can find ways to prevent this harm,” says Rogulja.

Referring to the value of this study to humans, she notes,”So many of us are chronically sleep deprived. Even if we know staying up late every night is bad, we still do it. We believe we’ve identified a central issue that, when eliminated, allows for survival without sleep, at least in fruit flies.”