Is psychopathy untreatable? Why researchers are starting to change their minds.

Image source: Pixabay

- Psychopathic individuals generally show impairments in several brain regions, a finding that’s helped to promote the view that psychopathy is virtually untreatable.

- Still, there’s been no concrete evidence to support this view.

- New treatments show some promising signs that psychopathy is treatable, even if it’s not curable.

Treating psychopathy has long seemed like a lost cause to many forensic practitioners and psychologists.

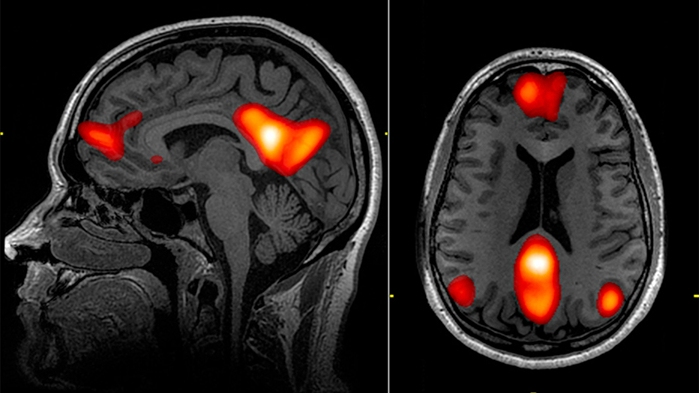

One reason is that psychopaths lack the neural “equipment” that enables them to empathize with others, and brain imaging studies show that psychopaths seem to have irregular mirror neuron systems, as well as less gray matter in regions of the brain associated with emotion regulation and self-control.

Psychopaths also don’t respond well to punishment: Prisoners who score high on the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCL-R), the most commonly used measure of psychopathy, are much more likely to commit violent crimes upon release. That’s partly why psychopaths represent 25 percent of prisoners, even though they represent 1 percent of the general population.

A 2006 empirical review of psychopathy treatments noted:

“… psychopaths are fundamentally different from other offenders and that there is nothing ‘wrong’ with them in the manner of a deficit or impairment that therapy can ‘fix.’ Instead, they exhibit an evolutionarily viable life strategy that involves lying, cheating, and manipulating others.”

But is this kind of “clinical pessimism” warranted? According to Rasmus Rosenberg Larsen, a lecturer at the University of Toronto Mississauga who recently published a review of decades of studies on psychopathy in the Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, this view is largely based on “erroneous, unscientific conclusions,” and it’s counterproductive to developing effective treatments for psychopathy.

“A lot of what people understand about psychopaths is not really rooted in research reality,” Larsen told U of T News. “There was no evidence for the hard claim that a psychopath cannot be treated successfully. There was also no evidence that treating a so-called psychopath will result in faster recidivism or that they will be worse afterwards. In fact, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that conventional treatment programs have positive impacts on psychopaths. This is important because it informs how we prioritize treatment and rehabilitation efforts.”

Larsen

Larsen noted that many psychopathic criminals seem to benefit from the same standard treatments administered to other offenders. But more interesting are the recent approaches that have been used to treat psychopathy in recent years, the results of which, Larsen wrote, show that “optimism is generally warranted.”

One of the most promising interventions is the “Decompression Model.” This approach, developed by staff at the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center in Wisconsin, rewards psychopathic individuals for positive behavior instead of punishing them for negative behavior.

“What starts out as a pat on the shoulder graduates to a candy bar, which graduates to the right to play video games, and so on and so forth,” reads an article published by Real Clear Science. “The youth were being introduced to the simple benefits of social society.”

Cognitive empathy

The results showed that youths in the program had a 34 percent lower recidivism rate compared to juveniles in other centers, and that they were 50 percent less likely to commit a violent crime. What this rewards-based treatment seems to promote is cognitive empathy, which is essentially the ability to see things from another person’s perspective. The treatment doesn’t necessarily help psychopaths with emotional empathy, which is generally described as:

- Feeling the same emotion as the other person

- Feeling our own distress in response to their pain

- Feeling compassion toward the other person

Treatable, if not curable

Given the neuroplasticity of the brain, it remains an open question whether any kind of intervention could significantly change the structure of a psychopath’s brain. It’s also important to note that psychopathy exists on a spectrum; there’s no clear line distinguishing a psychopath from a neurotypical person, though in the U.S. it’s defined as scoring a 30 out of 40 on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised.

Psychopathy may never be “cured.” But for many, developing treatments that measurably improve behavior would be enough, as Barbara Bradley Hagerty, a journalist who’s written about the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center, told NPR:

“… when you talk to the psychologists at Mendota they say, ‘Hey, we’re not looking for Mother Teresa. We’re just happy if they’re not committing armed robbery and killing people.'”