Is There a Link between Creativity and Mental Illness?

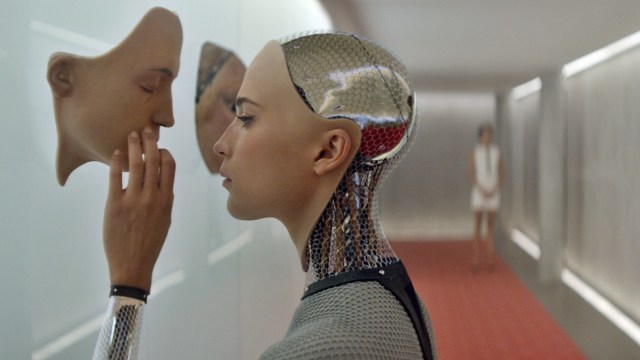

The world was recently saddened with the deaths of rocker Chris Cornell and Linkin Park frontman Chester Bennington. Each committed suicide after wrestling for years with major depression. Comedians, musicians, writers (gulp!), and other creative types are known to struggle with mental illness. This is by no means a new observation. Aristotle once said, “No great genius has ever existed without a strain of madness.”

Michelangelo, Beethoven, van Gogh, Emily Dickinson, and so many others who through their work, altered the course of human existence, were also known to wrestle with powerful inner demons. That doesn’t prove a link, however. We could as a society merely romanticize the artist riddled with madness and eccentricity. So has science found a link? And if so, what can it tell us about this relationship?

There have been two approaches to investigating this. The first is conducting interviews with prominent creative people or analyzing their work. The Lange-Eichbaum study of 1931 was the first to really delve into the question. Over 800 well-known geniuses at the time were interviewed. Only a small minority were found to be free of any mental health issues. Most recent studies have strengthened a belief in this correlation.

Chris Cornell. Getty Images.

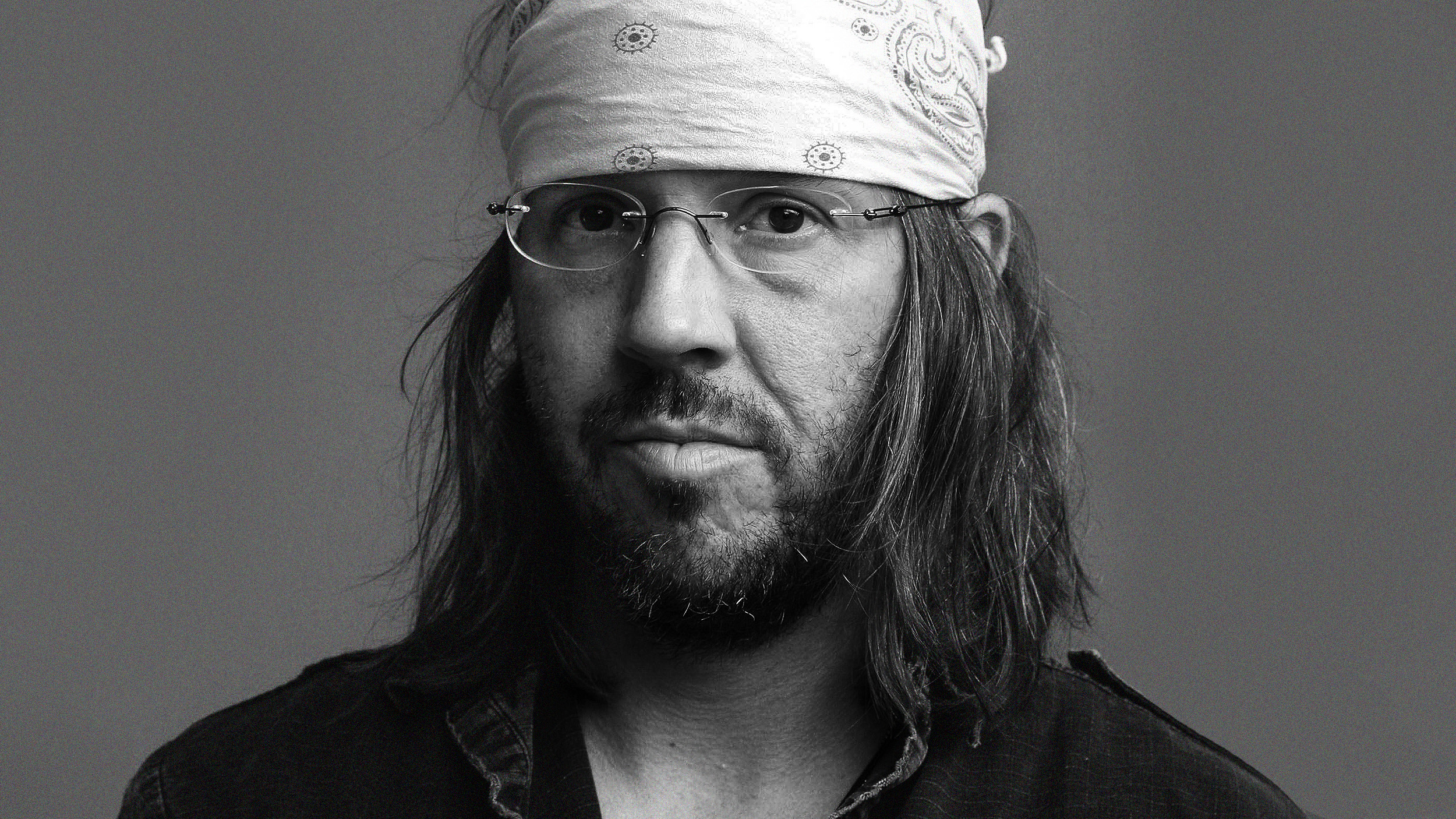

Besides this interview approach or analyzing someone’s work for signs of mental illness, as has been done with Virginia Woolf’s writing, there’s another approach. This is to look at creativity among those with mental illness. Some studies have shown that those who are highly creative also run a higher risk of depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.

Bipolar has been particularly associated with creativity. One study which screened 700,000 Swedish teens for intelligence, found that those who were exceptionally creative, were also four times more likely to have bipolar. This condition is typified by the patient’s mood alternating between phases of mania or extreme happiness, and crippling depression. Researchers here also found a strong correlation between writers and schizophrenia. Yikes.

A 2013 study, published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, found that people who made their living through either a scientific or creative occupation, were more likely to have bipolar, or a relative with the condition. Researchers here concluded that, “being an author was specifically associated with increased likelihood of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, unipolar depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, and suicide.” We writers just can’t catch a break.

Writer’s may be particularly prone to mental illness. David Foster Wallace. Getty Images.

Clinical psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison of Johns Hopkins University told Live Science that those who have bipolar and are coming out of a depressive phase, often see a boost in creativity. When this occurs, the frontal lobe of the brain shows a lot of activity, similar to what takes place when someone is concentrating in creative pursuit. That’s according to neurobiologist James Fallon of UC-Irvine.

Another reason may be the sheer volume of ideas that flood the mind of someone with bipolar in a manic state. A larger number of ideas increases the chance of having a really unique one. Associate Dean and mental health law professor Elyn Saks of USC, said that those with a psychiatric disorder have less of a mental filter. They can live comfortably with cognitive dissonance or holding two competing ideas in the mind simultaneously. This allows for them to find tenuous associations others might miss.

Some researchers have wondered if there’s a genetic connection. A 2015 study published in the journal Nature Neuroscience, suggests that there is. This project included the data of some 86,000 Icelanders and 35,000 Swedes and Danes. A team of international researchers conducted the study, led by Kari Stefansson, founder and CEO of deCODE, an Icelandic genetics company.

The suicide of Robin Williams shocked many worldwide, who never knew he wrestled with depression. Getty Images.

Stafansson and colleagues found that creative professionals and those who were members of arts societies, had higher polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Polygenes are those which are too small to enact influence on their own, but in concert with others can cause certain variations to occur.

Critics point out that the link in Icelandic study is a weak one. They say that although we’re familiar with famous cases of creatives who were touched by psychological turmoil, this isn’t necessarily the norm. Psychology professor Albert Rothenberg of Harvard University, is one such detractor. In his 2014 book, Flight from Wonder: An Investigation of Scientific Creativity, he interviewed 45 Nobel laureates. Rothenberg found no association between creativity and psychiatric disorders. None of the laureates had any in any notable way.

In an interview with The Guardian Rothenberg said,

The problem is that the criteria for being creative is never anything very creative. Belonging to an artistic society, or working in art or literature, does not prove a person is creative. But the fact is that many people who have mental illness do try to work in jobs that have to do with art and literature, not because they are good at it, but because they’re attracted to it. And that can skew the data. Nearly all mental hospitals use art therapy, and so when patients come out, many are attracted to artistic positions and artistic pursuits.

Though several studies point to a connection, it isn’t definitive. More research will be needed, especially to prove whether or not there are genetic underpinnings. Say that there is a connection and we isolate the genes or polygenes responsible, would curing a potential creative genius of say bipolar disorder or allowing them to manage it well, kill off their creativity?

If it did, would we be robbing society of potentially groundbreaking advancements or colossal works of art? And if a creative genius who midwifed such works for the benefit of humanity was not cured, on purpose, and in the aftermath committed suicide, would the doctors who reserved treatment be complicit? Would society? These are thorny moral questions we might have to weigh in on, someday soon.

Until then, if you want to learn more on this topic, click here: