To get clean, addicts are turning to a dangerous hallucinogen

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

- The opioid crisis in the U.S. isn’t showing any signs of slowing down, and tens of thousands of addicts die every year from opioid abuse.

- Some centers outside of the U.S. are treating opioid addiction with ibogaine, a powerful hallucinatory drug.

- The drug is understudied and known to be toxic to humans, but some addicts are willing to take the risk.

Across the U.S., opioid addicts are boarding planes to fly to Mexico, Canada, Costa Rica, and other countries in pursuit of a high-risk, high-reward treatment for their addiction. This treatment is illegal in the U.S. — it’s caused deaths before, and the research on its efficacy is still in its infancy. It’s called ibogaine, a hallucinatory, toxic drug extracted from the root bark of the iboga tree in Western Africa.

It’s no surprise, that opioid addicts are going to these extreme lengths to get clean. The rehabilitation community claims that it only has an overall 30% success rate for treating opioid addiction, and there’s evidence that even that modest number is inflated. Meanwhile, deaths from heroin use have increased seven-fold between 2002 and 2017. Even if the treatment is dangerous and untested, for some, the risk is worth it.

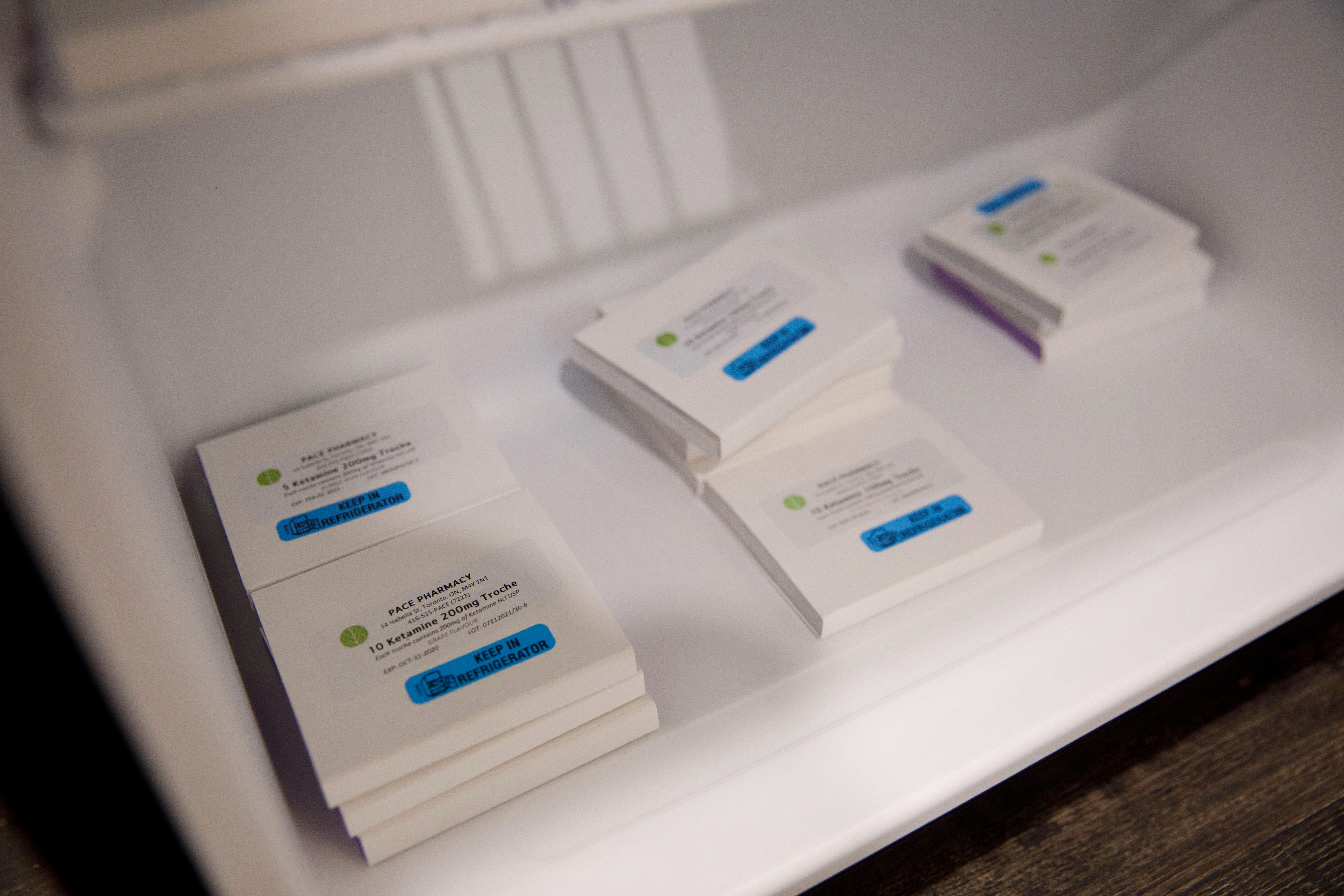

Powdered ibogaine.

Wikimedia Commons

The effects

Ibogaine produces powerful hallucinations for four to six hours. As a psychedelic, its most distinguishing characteristic is its oneirogenic quality, meaning that it produces a dream-like sensation. Users have reported it feels like “a waking dream.” During an interview with the New York Times, one user said that after taking the drug, “My face opened up like a zipper […] It’s like somebody pulled my face apart and looked into me. Then a white light came on, and suddenly I saw all these faces, like on a movie screen.” Although it might not sound like it, the user said, “It was pleasurable, relaxing.”

In the Bwiti religion in Western Africa, the drug is believed to enable communication with the dead. In light doses, Gabonese hunters use the drug as a stimulant to assist in chasing their prey, and it was sold as a stimulant in France between 1930 and 1960 before it was banned.

While its stimulating and psychedelic effects are interesting, opioid addicts aren’t traveling to far flung locations just for a hallucinatory experience. They’re traveling for what is perhaps the drug’s least-understood property: its apparent ability to kill addiction in its tracks. Users report that taking ibogaine both reduces cravings and relieves the pain of withdrawal from a number of drugs. However, most of the evidence for this effect is anecdotal, beginning with an account by a man called Howard Lotsof.

The evidence

Lotsof was a researcher who, at the age of 19, was addicted to heroin. In pursuit of a recreational hallucinogenic trip, Lotsof took the then-obscure ibogaine along with five other friends, also heroin addicts. After the experience, they all noted a significant decrease in their cravings for heroin and in the severity of their withdrawals. After this experience, Lotsof became something of an ibogaine evangelist, authoring several research papers and developing a number of patents related to the drug’s use for addiction treatment. His story is one of many anecdotal reports of ibogaine’s efficacy.

However, there has also been some empirical evidence to support these reports. Human studies have been rare, but studies on animals hooked on cocaine and opioids consistently show that ibogaine administration reduces the animals’ cravings for their drug of choice.

The limited number of human trials have shown some promise too; in most of these studies, participants reported they abstained from opioids for at least a few weeks, and many others reported abstaining for more than a year. Unfortunately, there isn’t more data out there on ibogaine’s effect on humans, and there’s good reason why.

Ibogaine is produced from the root powder of the iboga tree (pictured above).

Wikimedia Commons

Ibogaine’s risks

Aside from its psychedelic and addiction-quashing properties, ibogaine comes with a major downside. Sometimes, it will produce a potent cardiac condition called long QT syndrome, in which a portion of the heartbeat is elongated, which can cause fainting, palpitations, seizures, or sudden death.

In 1999, researchers conducted a human study on the effects of ibogaine on opioid withdrawal. Out of the 33 participants, one 24-year-old woman complained of muscle aches and nausea 17 hours after receiving ibogaine. An hour later, she suffered from respiratory failure, and died soon after. Participants have died in other studies as well, generally due to cardiac complications. In fact, ibogaine is estimated to have a mortality rate of 1 in 300.

Considering this relatively high mortality rate, ibogaine has been approached with caution both from the scientific community and from the more reputable ibogaine treatment clinics. Unfortunately, reputable ibogaine treatment clinics are few and far between, and, considering the risks involved, trained medical staff and proximity to a hospital are a must.

Although the empirical evidence is unclear and the risks are high, opioid addicts are still boarding planes to fly to countries where they can receive this treatment. It’s difficult to see whether the risk of dying from ibogaine outweighs the risk of dying from opioid addiction. Then again, there were 63,600 deaths from drug overdoses in the U.S. in 2016. What’s more, it’s impossible to quantify how valuable a sober life might be to an addict. Ultimately, all we can say about ibogaine is that more research is needed to definitively confirm or deny its efficacy. Until then, it’ll be hard to stop desperate people from doing desperate things.