How humans evolved to live in the cold

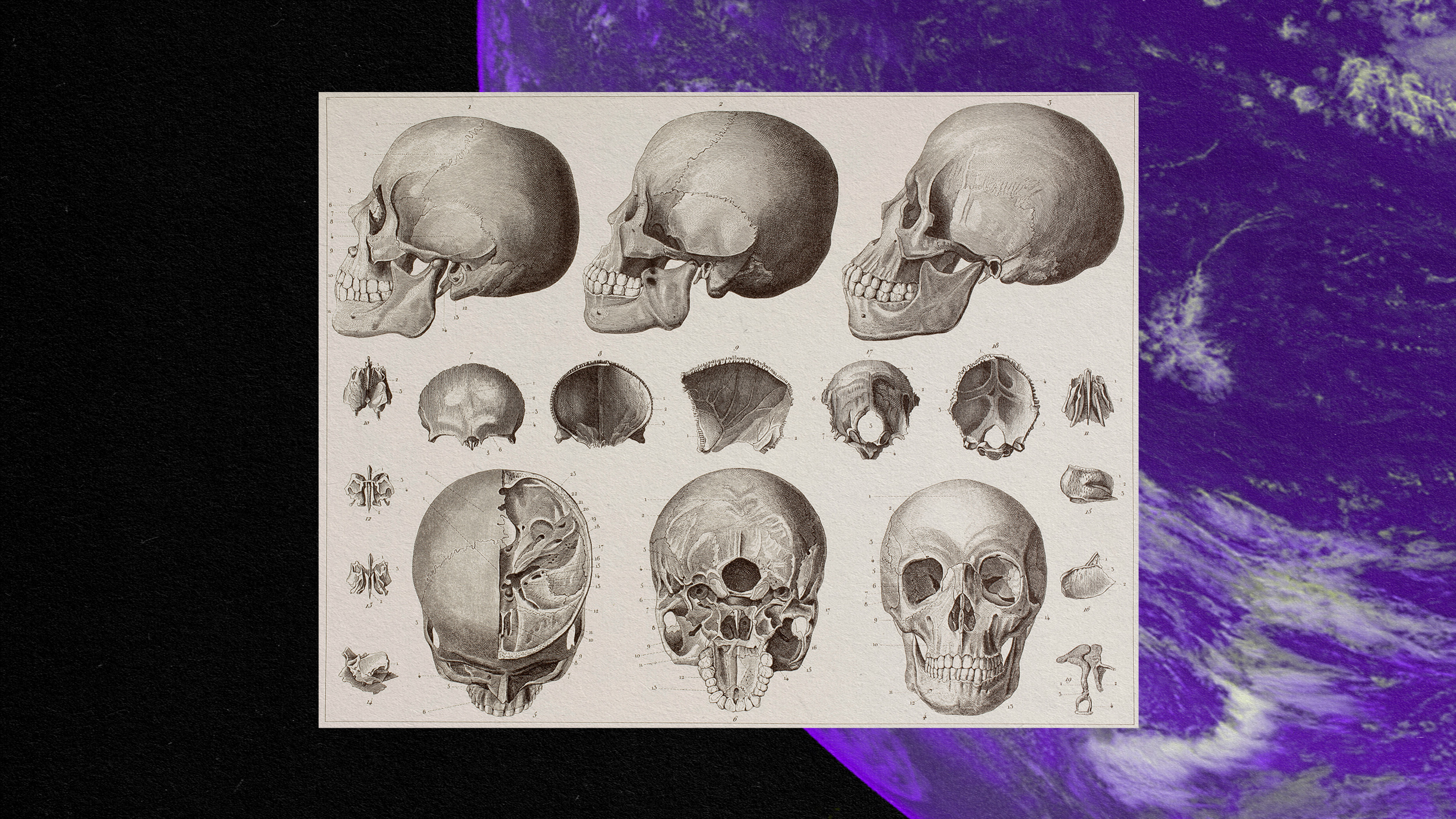

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

- According to some relatively new research, many of our early human cousins preceded Homo sapien migrations north by hundreds of thousands or even millions of years.

- Cross-breeding with other ancient hominids gave some subsets of human population the genes to contend and thrive in colder and harsher climates.

- Behavioral and dietary changes also helped humans adapt to cold climates.

Humans emerged from a tropical environment. For the most part, our bodies are not well adapted to the cold. You might be feeling that this winter as you battle the frost winds and dream of sunnier days. The fact that we can live in cold climates is a result of many behavioral adaptations. Though, in recent years we’ve also found that some populations have genetically evolved to be able to better adapt and live in the cold.

The ability to survive and thrive in a cold environment comes from a few practical advances. One is the ability to adapt to the environment through clothing and shelter. Humans also have had to change their diet, as the local flora and fauna in colder areas doesn’t contain those delicious primate fruits our early ape-like ancestors originally ate in the warm tropics.

Scientists have discovered that many early hominids left the cradle of humankind a lot sooner than we initially hypothesized. We’ve learned that through a combination of technology, cross-breeding hominids and some genetic mutations, humans were able to dominate all parts of the globe — even flourishing in the coldest of regions.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

Environmental adaptation through early technology

Throughout human evolution, a wide range of environmental change was also taking place. Many climate fluctuations included drastic cooling and desertification. The origin and emergence of our species through early hominins was heavily influenced by these changes. Humans and chimpanzees branched off of a common ancestor some 6 to 8 million years ago.

One of our distant cousins, the Neanderthal, branched off into Europe before Homo sapiens left the African plains. We can learn a lot about human’s eventual adaptation to the cold through this subspecies of human – Homo neanderthalensis. They endured many large shifts in climate as they contended with many waning glacial and interglacial periods. Neanderthals were able to adapt for example by hunting cold-adapted animals in the winter like reindeer and then hunting red deer in warmer periods. They also tended to migrate southwards during warmer conditions.

The first known stone tools that date back to around 2.6 million years ago were instrumental in allowing us to shift our diet and interact with our new surroundings. Simple tools, which included fractured stones, gave us a way to crush, slice and pound up new food sources.

These basic tools gave us the ability to eat a wide range of foods no matter where we migrated to. Meat, for example, is a food that could be obtained from whatever environment early humans encountered and moved to. This could be a major contributing factor in our collective human march northwards.

Early hominid migrations north

Scientists have found evidence that early hominids groups migrated to the far north in a much earlier timeframe than we had originally believed. The fossil evidence at Dmanisi shows that some hominids migrated to the Anti-Caucasus mountains, which is a similar northern latitude to modern day New York or Beijing. This would have been a very difficult place to exist in for a species that had just come from Africa.

Paleoanthropologist Martha Tappen, who was part of the Dmanisi research team stated:

In terms of hominids spreading out of Africa, it seems that they did not spread with other fauna. That they made it to the higher latitudes without other animals moving at the same time tells you humans made it out of Africa not because the environment was changing or because the biome was moving… They went of their own volition.

What confuses researchers is that these hominids were found thousands of miles north of Africa without having any advanced technology to take them there.

Tapper goes on to say:

At the higher latitudes, you’re confronting seasonality for the first time. . . They were experiencing winter. No other primate lives where there’s no fruit in winter. There may be a dry season, but there’s not a cold winter like these individuals in Dmanisi were experiencing.

It’s believed that by shifting to a more meat-centric diet that they were able to live in such an environment. But dietary changes are just one piece of the puzzle for how and why humans were able to evolve and live in the cold.

Interbreeding with other hominid species

Research suggests that by cross-breeding with Denisovans, many subsets of the human population had a boosted immune system and alterations in skin color. This also led to other cold tolerance adaptations.

For example, the EPAS1 gene, which is found in Tibetan populations, allows them to function at higher and colder altitudes. It’s believed that this originated in our Denisovans cousins. While Denisovans and also Neanderthals originated from a common ancestor in Africa as well, they also spent hundreds of thousands of years in Eurasia before modern humans migrated there as well.

Breeding with our other Eurasian cousins gave us some genetic chutzpah to brave the cold.

Researchers also found that another Denisovans gene gave us an additional ability to handle colder temperatures. To test this hypothesis, researchers reviewed genomic data from a number of Greenlandic Inuits and then compared that to certain genes with Denisovans data.

It was found that there were similarities in the TBX15 and WARS2 genes, both which increase heat generation from body fat. Their conclusion was that genes found in the Inuit population were divergent from nearly every other human population, thus suggesting these genes were from a much different gene pool. Either it was from the Denisovans or another ancient hominid species breeding with them.

Mitochondrial DNA mutations in cold environments

According to research from the Biological Sciences and Molecular Medicine at the University of California Irvine, scientists discovered that after early humans had migrated to colder climates, their chance of survival increased when their mtDNA was mutated and generated greater body heat production.

Professor Douglas C. Wallace states that:

In the warm tropical and subtropical environments of Africa it was most optimal for more of the dietary calories to be allocated to ATP to do work and less to heat, thus permitting individuals to run longer, faster and to function better in hot climates… In Eurasia and Siberia, however, such an allocation would have resulted in more people being killed by the cold of winter. The mtDNA mutations made it possible for individuals to survive the winter, reproduce and colonize the higher latitudes.

A combination of all of these factors eventually led us to where we are today.