Ebola is now largely curable, new clinical trials suggest

Photo credit: AUGUSTIN WAMENYA / Getty Contributor

- The Democratic Republic of Congo has been suffering a major Ebola outbreak since August 2018.

- In November 2018, a clinical trial began comparing the efficacy of four Ebola treatments.

- Two of those treatments — based on monoclonal antibodies — are nearly twice as effective as the standard treatment.

In August 2018, an Ebola outbreak struck a conflict zone in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s North Kivu province. It soon spread elsewhere throughout the nation of 81.3 million people, many of whom are embroiled in battles over DRC’s valuable minerals. By April, the outbreak had become the second worst ever recorded, and by June it had killed at least 1,357 Congolese.

But a recent clinical trial that compared the efficacy of four Ebola treatments brings good news.

“From now on, we will no longer say that Ebola is incurable,” said Dr. Jean-Jacques Muyembe, the director general of the Institut National pour la Recherche Biomédicale in DRC, which has overseen the trial. “These advances will help save thousands of lives.”

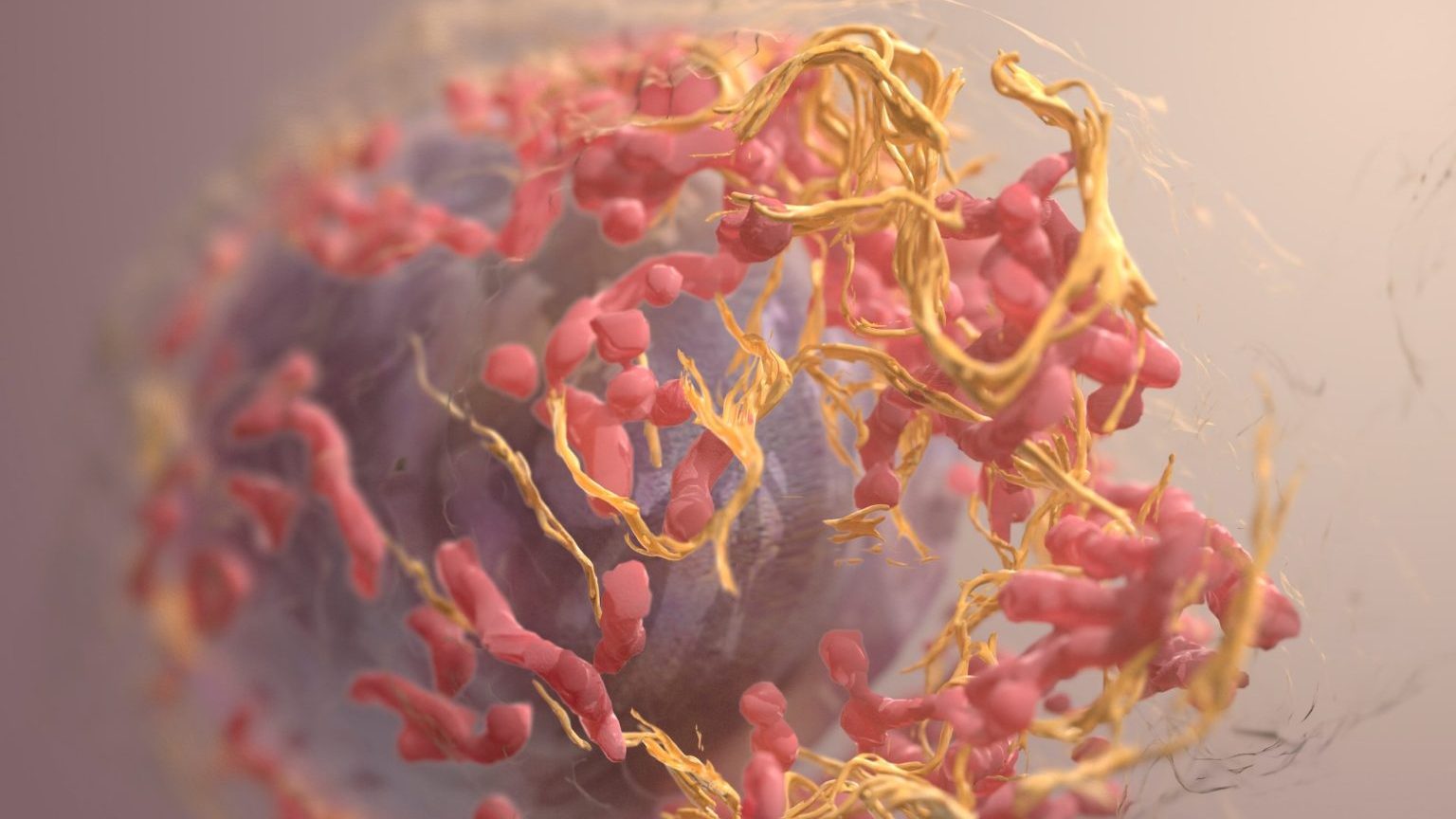

In November 2018, doctors in DRC began randomly assigning Ebola patients one of four treatments: an antiviral drug named remdesivir, or one of three drugs made of monoclonal antibodies, which are a set of immune cells cloned from a parent cell. ZMapp — one of the three drugs that use monoclonal antibodies — has long been considered the most effective treatment for Ebola. In the clinical trial, it helped lower mortality rates among Ebola patients to about 49 percent. (Patients who don’t receive any treatment have a mortality rate of roughly 75 percent.)

But two other drugs of the same class — a cocktail of monoclonal antibodies made by a company named Regeneron, and an antibody called mAb114 made by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases’ Vaccine Research Center — were much more effective, yielding an overall mortality rate of 29 and 34 percent, respectively. These drugs were developed by giving mice Ebola and then extracting the antibodies that the mice produced. Scientists then tweaked those mice antibodies so the human body would accept them. The two drugs will now be administered in every treatment center in DRC.

An illustration depicting how to safely bury people who died from Ebola. Image source: CDC’s Center for Global Health

The monoclonal antibodies-based drugs were especially successful at curing Ebola when patients took them soon after becoming sick, with Regeneron’s drug lowering mortality rates to just 6 percent. But one problem is that most Ebola patients in DRC wait an average of four days before coming to the hospital, which decreases the odds of survival and increases the odds of transmitting the disease — through bodily fluids — to people near them.

But health experts are optimistic about the new drugs.

“The more we learn about these two treatments, and how they can complement the public health response, including contact tracing and vaccination, the closer we can get to turning Ebola from a terrifying disease to one that is preventable and treatable,” Dr. Jeremy Farrar, the co-chair of the World Health Organization’s Ebola therapeutics group, told The Guardian. “We won’t ever get rid of Ebola but we should be able to stop these outbreaks from turning into major national and regional epidemics.”