New study shows how depression rises with the temperature

Pixabay Commons

- The study examined survey data reported by 2 million Americans between 2002 and 2012.

- The results showed that hotter and wetter months were associated with increases in mental health issues like stress and depression.

- Women and low-income Americans seem to have been most affected by the weather changes.

The United Nations’ top climate science panel recently warned that the world would see “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes” if global temperatures rise 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial averages in coming years. Such an increase would likely be catastrophic for millions of people, particularly those who live in island nations or along the world’s coasts.

Now, new research suggests rising temperatures could also have similarly disastrous effects on mental health.

The link between weather and mental health

A paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that exposure to hotter temperatures, increased precipitation and tropical cyclones was associated with an increase in mental health issues. These effects will likely hit women and low-income Americans the hardest, according to the research team led by Nick Obradovich, a data scientist at the MIT Media Lab.

“If we push global temperature rise into the 2 degrees-plus Celsius range, the impacts on human well-being, including mental health, may be catastrophic,” Obradovich told Inverse.

The team analyzed self-reported data of 2 million Americans who responded to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, a health survey, between 2002 and 2012. This survey, which included a location for each respondent, asked people to rate how stress, depression, and “problems with emotions” had affected their mental health over the past 30 days. The researchers then cross-referenced respondents’ answers with their location and weather records.

They found that, on average, people were slightly more likely to experience mental health problems during months in which the average temperature exceeded 86 degrees compared to months when average temperatures hovered between 50 and 59 degrees. The results showed less of a contrast in months when the average temperatures ranged from 77 to 86 degrees, suggesting that mental health issues increase as temperatures rise.

The results also showed that months in which there were more than 25 days of precipitation were linked to a 2-percent increase in the probability of mental health issues. What does more rain have to do with climate change? Rising temperatures leads to more evaporation, which puts more water vapor in the atmosphere where it’ll eventually come back to Earth as precipitation. The evaporation of more and hotter water also leads to an increase in tropical storms.

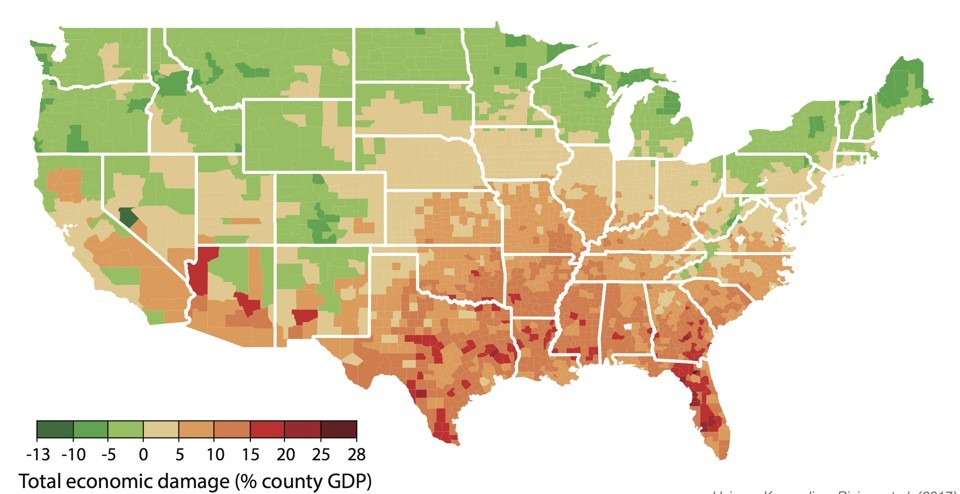

Image: Climate Central

Women and low-income Americans affected most

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the survey data showed that people hit by hurricanes between 2002 and 2012 were 4 percent more likely to experience mental health issues compared to Americans not affected by tropical storms.

Lastly, the team compared the links between weather and mental health along lines of gender and wealth, finding that females and low-income Americans were both 60 percent more likely to experience mental health issues during the hottest months compared to males and high-income Americans, respectively.

Still, the team cautioned that the study results revealed correlations and not necessarily causes.

“We can’t be sure,” Obradovich told Inverse. “It could be via the impacts of heat on sleep, on daily mood, on physical activity rates, on heat-related illness, on cognitive performance, or any complex combination of the above. Unfortunately, these processes are so complex that we can’t easily identify precisely which mechanism is driving our results.”