Here’s a map of Mars with as much water as Earth

Image: A.R. Bhattarai, reproduced with kind permission

- Sci-fi visions of Mars have changed over time, in step with humanity’s own obsessions.

- Once the source of alien invaders, the Red Planet is now deemed ripe for terraforming.

- Here’s an extreme example: Mars with exactly as much surface water as Earth.

Mars – and Martians – were a staple of 1930s pulp science fiction.Image: ScienceBlogs.de – CC BY-SA 2.0

“Oh, my God, it’s a woman,” he said in a tone of devastating disgust.

“Stowaway to Mars” hasn’t aged well. First serialised in 1936 as “Planet Plane” and set in the then distant future of 1981, the fourth novel by sci-fi legend John Wyndham (writing as John Benyon) could have been remembered mainly for its charming retro-futurism, if it weren’t so blatantly, offhandedly misogynistic.

Fortunately, each era’s sci-fi says more about itself than about the future. That also goes for how we see Mars. ‘Classic’ Martians, like the ones in H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds,” are creatures from a dying planet, using their superior firepower to invade Earth and escape their doom. That trope reflected 19th- and 20th-century fears about mechanized total warfare, which hung like a sword of Damocles over otherwise increasingly placid lifestyles.

Closer inspection of the Red Planet has revealed the absence of green men; and now we’re the dying planet – pardon my Swedish. So the focus has shifted from interplanetary war to terraforming the fourth rock from the Sun, creating something all those protest signs say we don’t have: a Planet B.

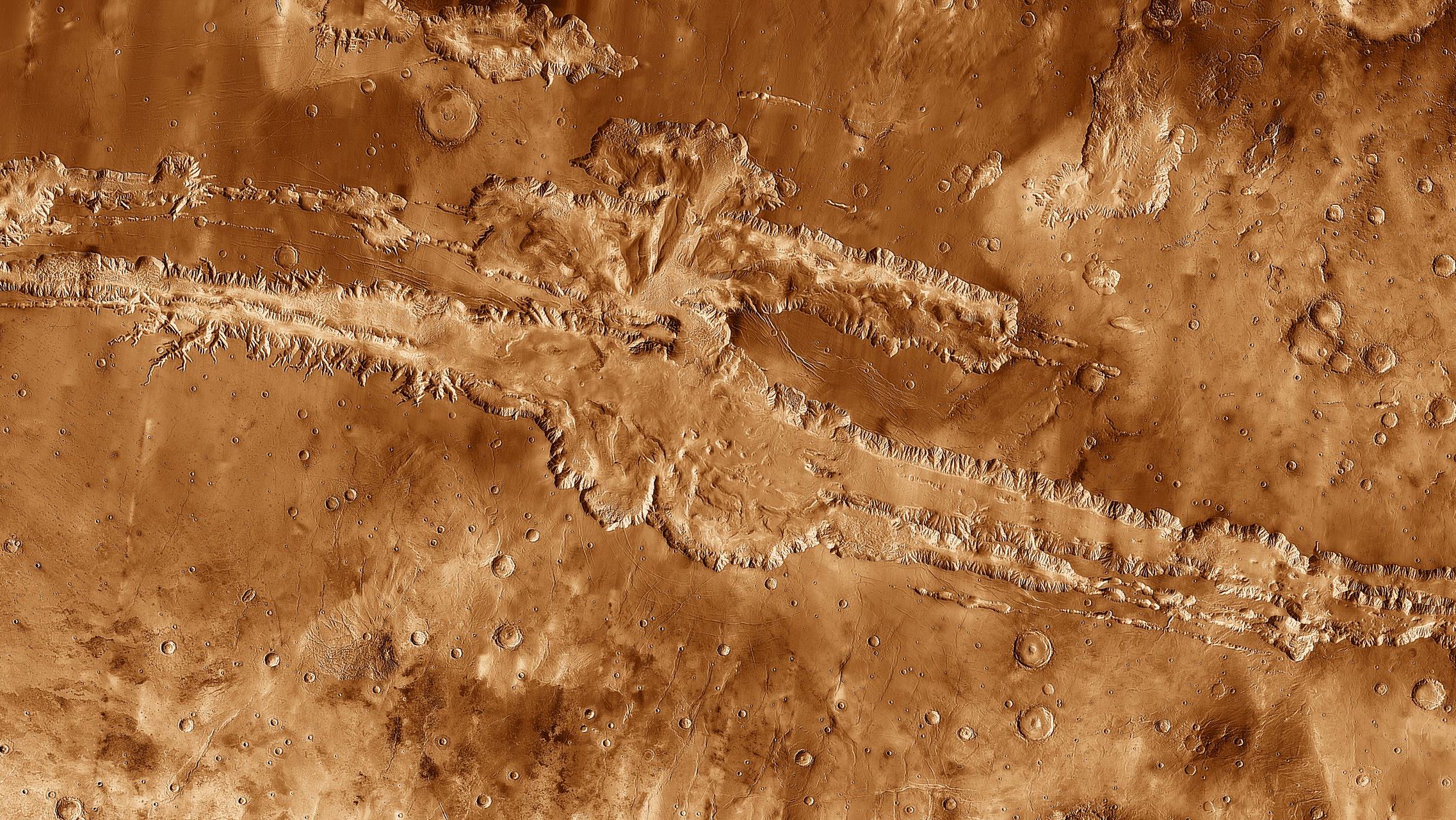

Mars today: red and dusty, dead and deadly.Image: NASA – public domain.

Cue Elon Musk, who doesn’t just build Teslas but also heads SpaceX, a program to make humanity an interplanetary species by landing the first humans on Mars by 2024 as the pioneers of a permanent, self-sufficient and growing colony.

Such a colony would benefit from an environment that doesn’t try to kill you if you take off your space helmet. Martian temperatures average at around -55°C (-70°F), and its atmosphere has just 1 percent the volume of Earth’s, in a mix that contains far less oxygen. Changing all that to an ecosystem that’s more like our own, would be a herculean task.

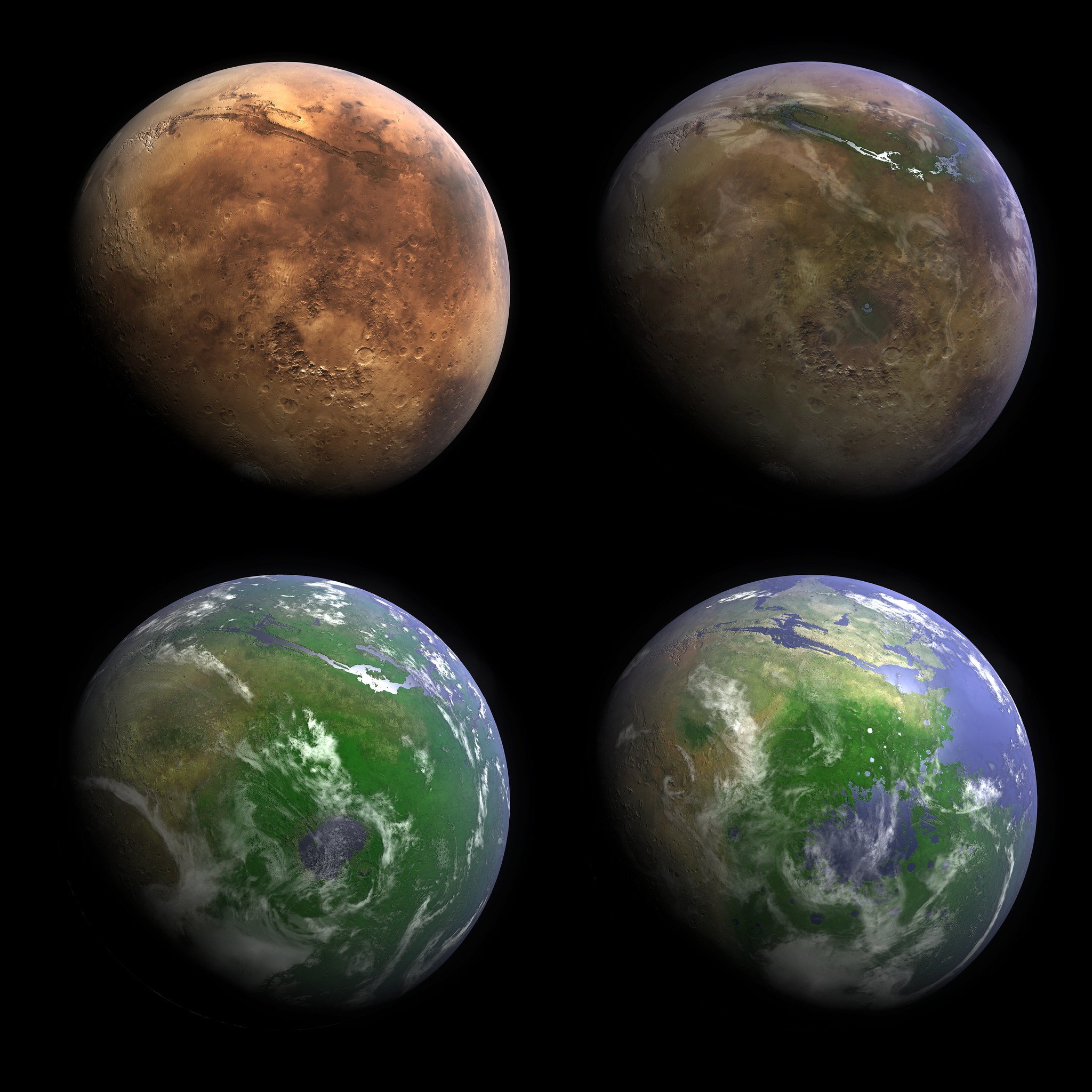

Before and after images of a terraformed Mars in the lobby of SpaceX offices in Hawthorne, California.Image: Steve Jurvetson / Flickr – CC BY 2.0

So how would Musk go about it? In August 2019, he launched a t-shirt with the two-word answer: ‘Nuke Mars’. The idea would be to heat up and release the carbon dioxide frozen at Mars’s poles, creating a much warmer and wetter planet – as Mars may have been about 4 billion years ago – though still not with a breathable atmosphere.

Alternatives to nuclear explosions: photosynthetic organisms on the ground or giant mirrors in space, either of which could also melt the Martian poles. However, many scientists question the logistics of these plans, and even whether there is enough readily accessible CO2 on Mars to fuel the climate change that Musk (and others) envision.

Ah, but why stop at the objections of the current scientific consensus? Sometimes, you have to dream ahead to see the place that can’t be built yet. In the lobby of SpaceX HQ in Hawthorne, California, Red Mars and Green Mars are shown side by side. The terraformed version on the right looks green and cloudy and blue – Earth-like, or at least habitable-looking.

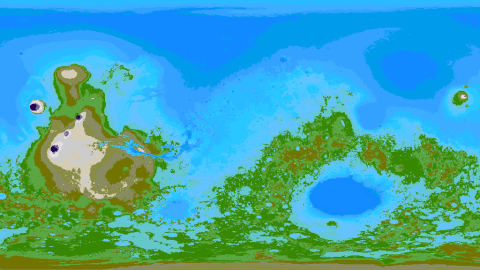

A map of Mr Bhattarai’s wet Mars, in the Robinson projection.Image: A.R. Bhattarai, reproduced with kind permission; modified with MaptoGlobe

But why stop there? This map looks forward to a Mars that doesn’t just have some surface water, but exactly as much as Earth – which means quite a lot. No less than 71 percent of our planet’s surface is covered by oceans, seas, and lakes. The dry bits are our continents and islands.

In the case of Mars, a 71 percent wet planet leaves the planet’s northern hemisphere mainly ocean, with most of the dry land located in the southern half.

Most of the dry land is connected via the south pole but is articulated in two distinct land masses. Both semi-continents are separated by a wide bay that corresponds to Argyre Planitia.

The one in the west is centered on Tharsis, a vast volcanic tableland. To the north, attached to the main land mass, is Alba Mons, the largest volcano on Mars in terms of area (with a span comparable to that of the continental United States).

It’s about 6.8 km (22,000 ft) high, which is about one-third of Olympus Mons, a volcano now located on its own island off the northwest coast of Tharsis. At a height of over 21 km (72,000 ft), Olympus Mons is the highest volcano on Mars and the tallest planetary mountain (1) currently known on the solar system. Olympus rises about 20 km (66,000 ft) above the sea level as shown on this map.

Spinning globe view of Mr Bhattarai’s wet Mars.Image: A.R. Bhattarai, reproduced with kind permission; modified with MaptoGlobe

Mars’s eastern continent is centered not on a plateau, but on a depression that on today’s ‘dry’ Mars is called Hellas Planitia, one of the largest impact craters in the Solar system. On the ‘wet’ Mars of this map, the crater is the central and largest part of a sea that is surrounded by land, a Martian version of the Mediterranean Sea. Perhaps one day this Medimartian Sea will be the Mare Nostrum of a new civilization.

To the northeast of the circular semi-continent is a large island that on ‘our’ Mars is Elysium Mons, a volcano that is the planet’s third-tallest mountain (14.1 km, 46,000 ft).

The map is the work of Aaditya Raj Bhattarai, a civil engineering student at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu (Nepal). Talking to Inverse, he said he hoped his map could help further the Martian plans of Elon Musk and SpaceX: “This is part of my side project where I calculate the volume of water required to make life on Mars sustainable and the sources required for those water volumes from comets that will come nearby Mars in the next 100 years.”

Images by Mr Bhattarai reproduced with kind permission. Check out his website. Planetary projection and spinning globe created via MaptoGlobe.

Strange Maps #1043

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

________

(1) The tallest mountain in the Solar system, planetary or otherwise, we know of today, is a peak which rises 22.5 km (14 mi) from the center of the Rheasilvia crater on Vesta, a giant asteroid which makes up 9 percent of the entire mass of the asteroid belt.