Hungry or horny? Whale makes record swim halfway across planet

- In a record first, a whale was observed migrating from the eastern Pacific to the western Indian Ocean.

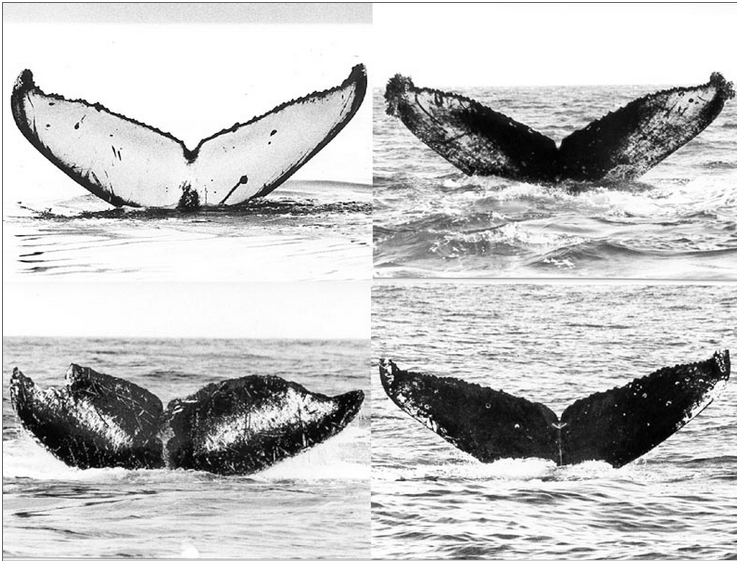

- The individual, a male humpback, was identified by the unique markings on its tail, a.k.a. “fluke.”

- Why? Scientists don’t know whether he was looking for food or a mate, or just was confused.

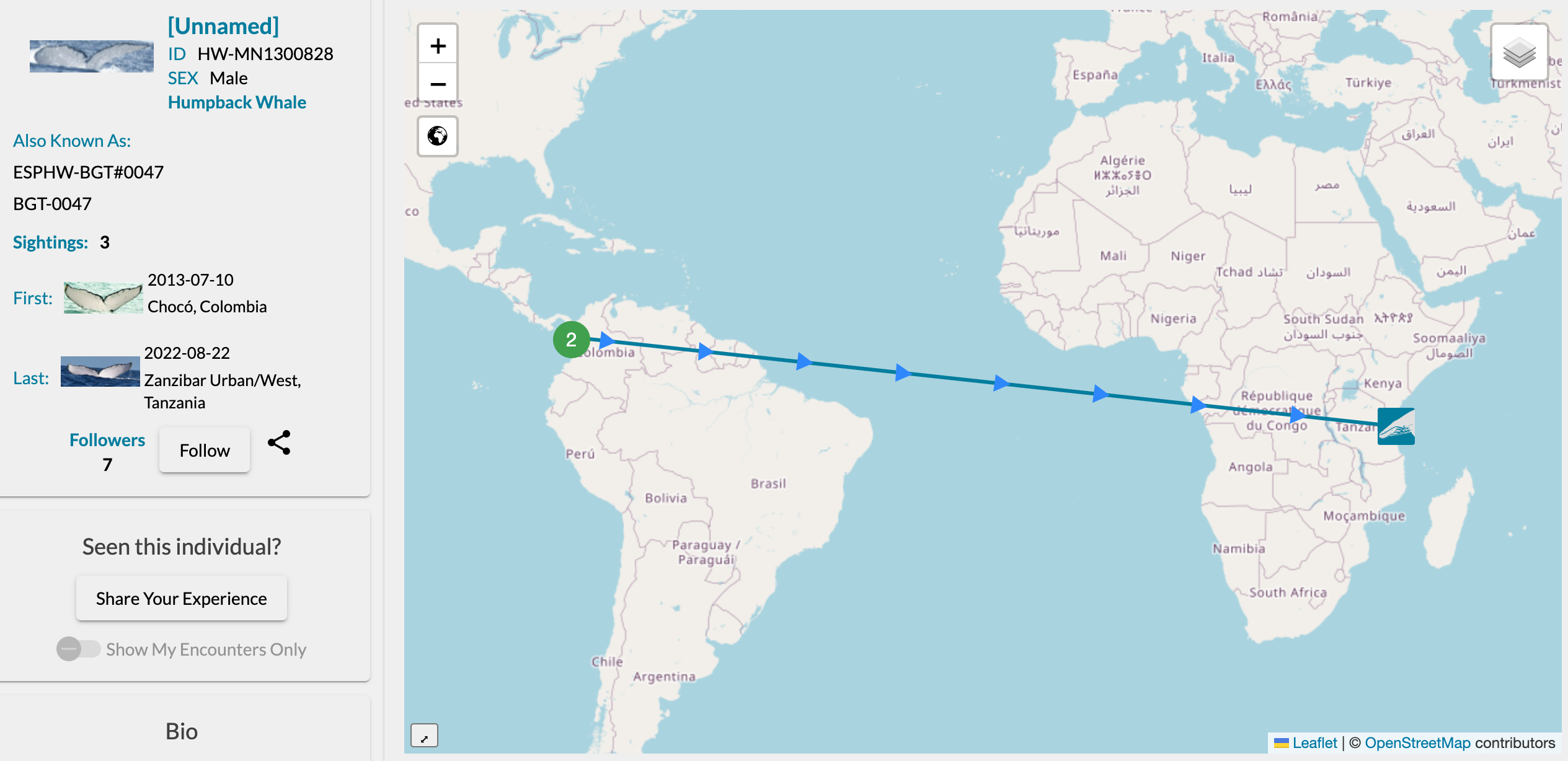

Was he hungry, horny, or just confused? Scientists don’t know why a male humpback whale, unceremoniously labeled HW-MN1300828, showed up in the Zanzibar Channel, off the coast of Tanzania, in August of 2022.

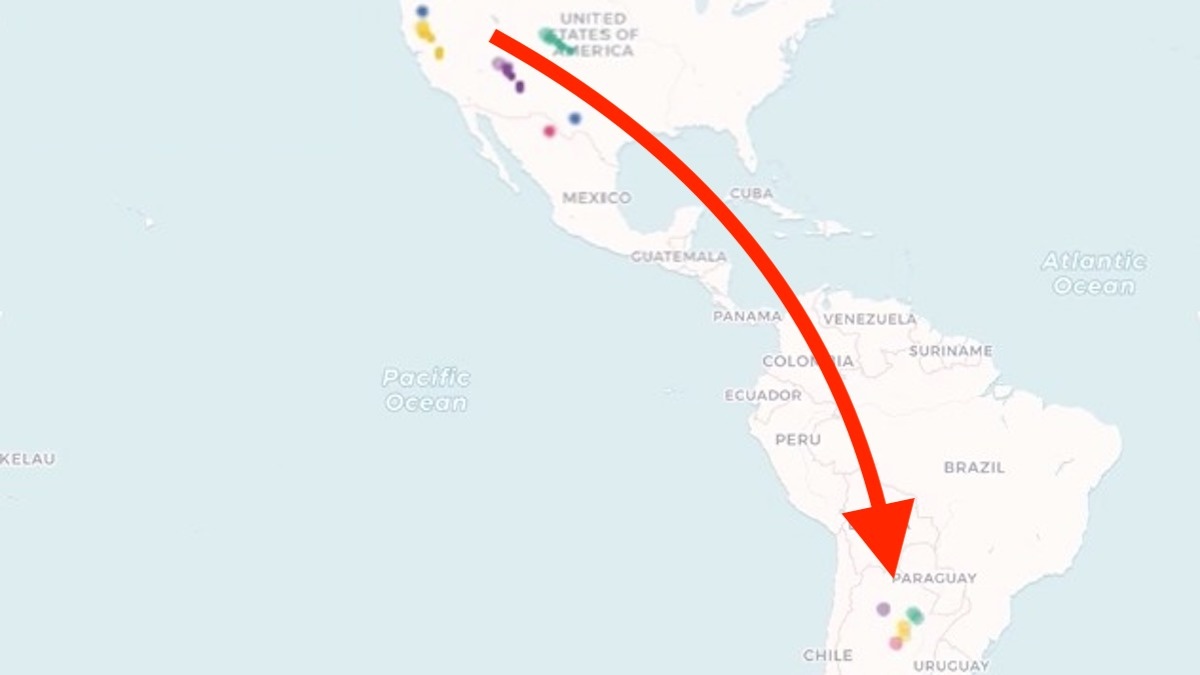

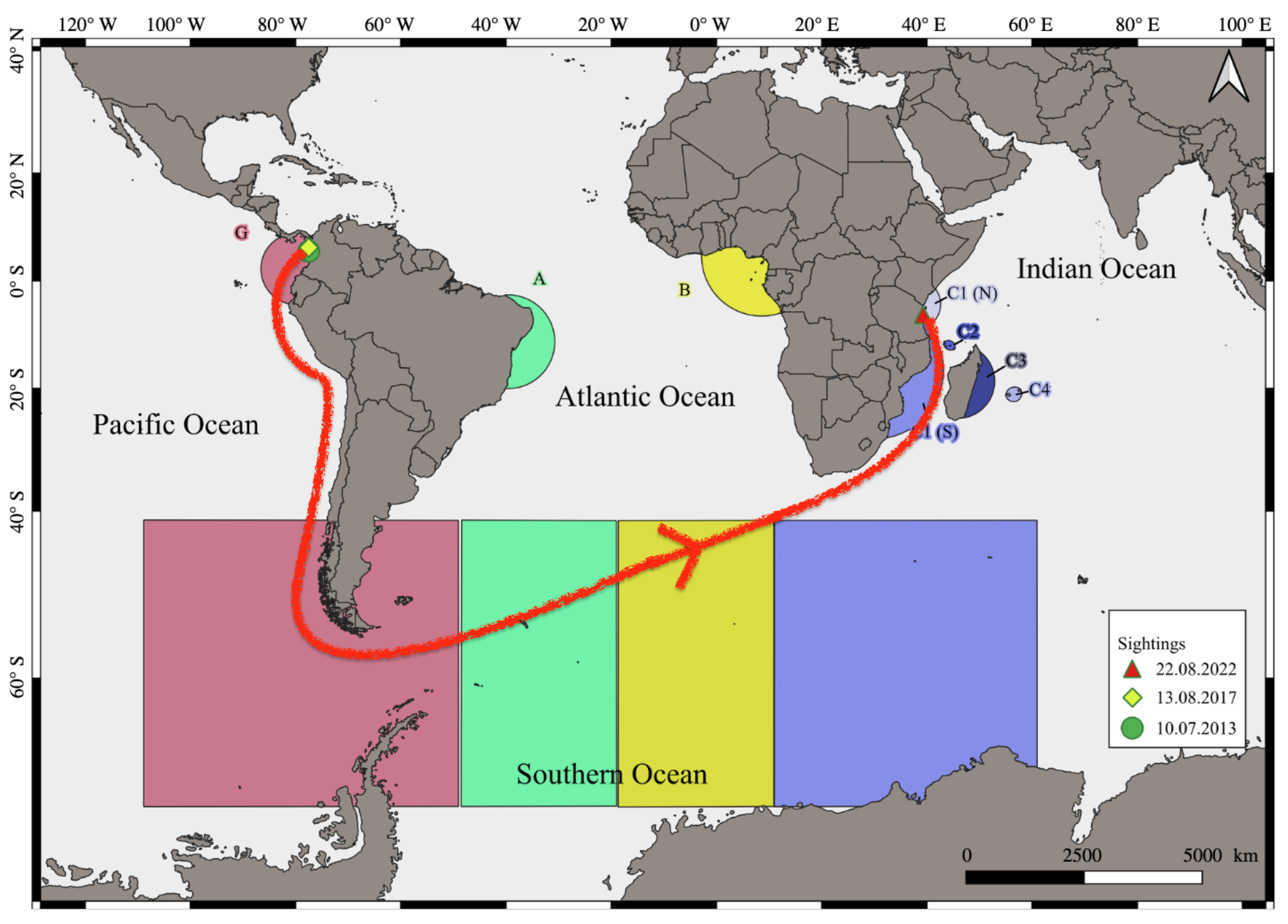

What they do know is that he traveled far — farther, in fact, than any other whale ever recorded. The individual was spotted off Colombia’s Pacific coast in 2013 and 2017. The shortest distance from there to Zanzibar is just over 13,000 km (more than 8,000 miles).

A 5,000-mile commute

That straight line crosses both South America and southern Africa, however. Since whales don’t travel over land, the actual journey is likely to have been at least 18,000 km (11,000 mi).

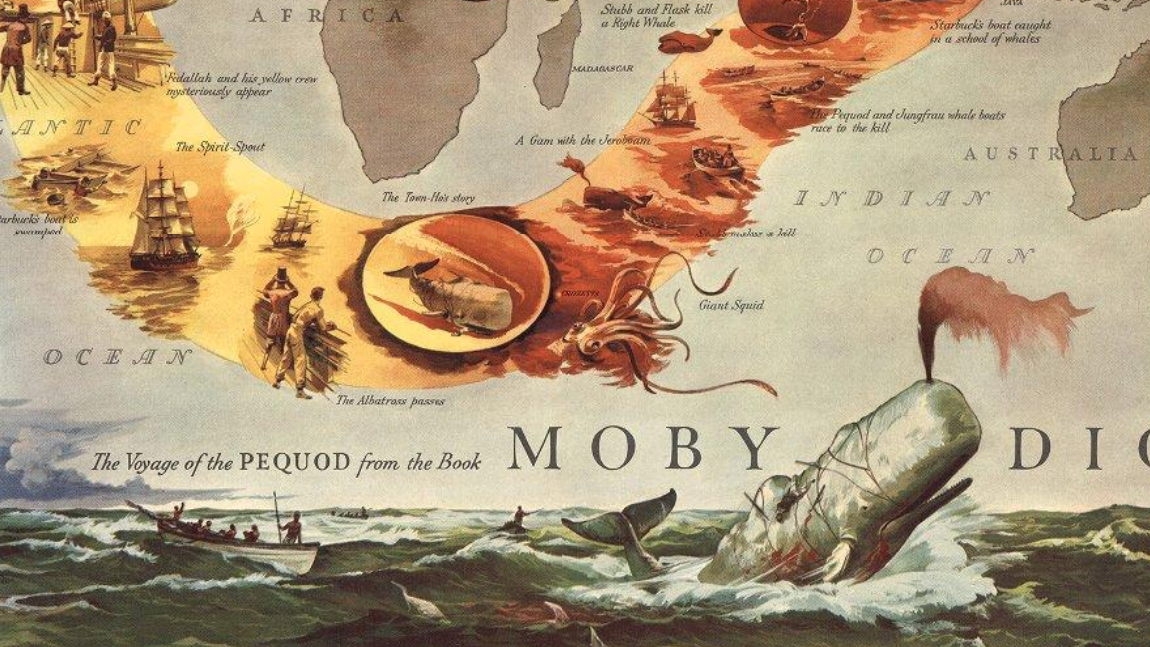

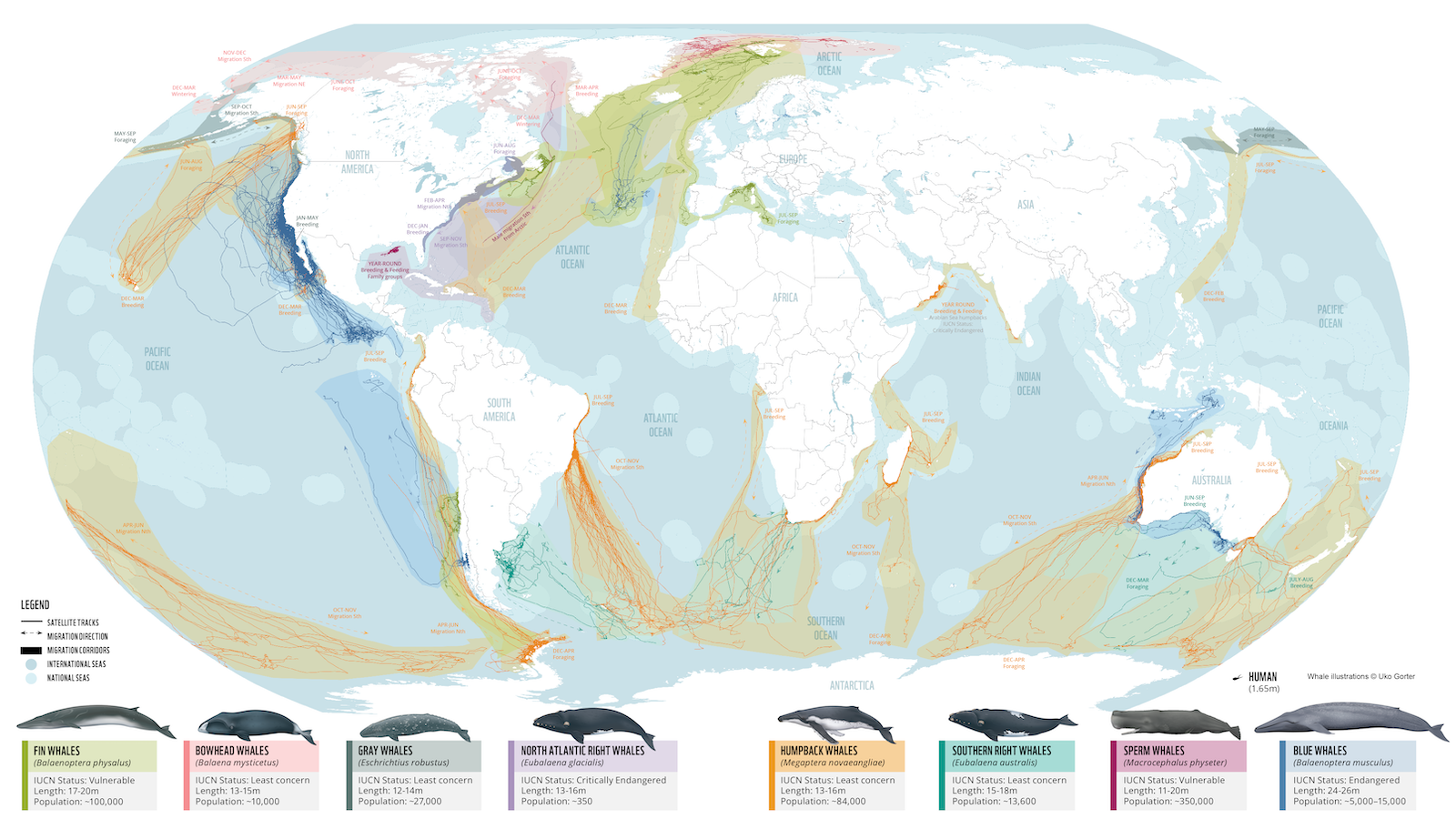

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) live in all the world’s oceans, and their seasonal migrations are among the longest of any mammal species. Each year, they commute back and forth up to 8,000 km (5,000 mi) between their tropical breeding grounds, near the equator, and their colder feeding grounds, near the poles.

These migration routes typically remain stable over the years, as humpbacks display strong “site fidelity” to specific breeding grounds. As a result, the global humpback whale population can be divided into distinct breeding stocks, with limited exchange between them.

Put differently: While humpbacks regularly swim long distances north to south and back again), they usually don’t migrate far east to west, or vice versa.

Our friend with the unwieldy name is a rare and notable exception, both in direction and distance. It’s the first recorded case of a humpback whale alternating between breeding grounds in the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Swimming the latitudes

But it’s not the first time in recent decades that humpbacks have been observed to deviate from their usual migration patterns, swimming the latitudes instead of the longitudes.

- In 1998, a female humpback previously photographed off Ecuador in 1996 was spotted again near Brazil, having traveled around 12,000 km (7,500 mi).

- In 2001, another female seen near Brazil in 1999 was recognized off the coast of Madagascar. Both places are separated by at least 9,800 km (6,000 mi).

- In 2002, a subadult male spotted off Madagascar in 2000 resurfaced — literally — off the coast of Gabon.

Are such latitudinal migrations increasing, or are scientists just getting better at observing them? Probably both, but certainly the latter.

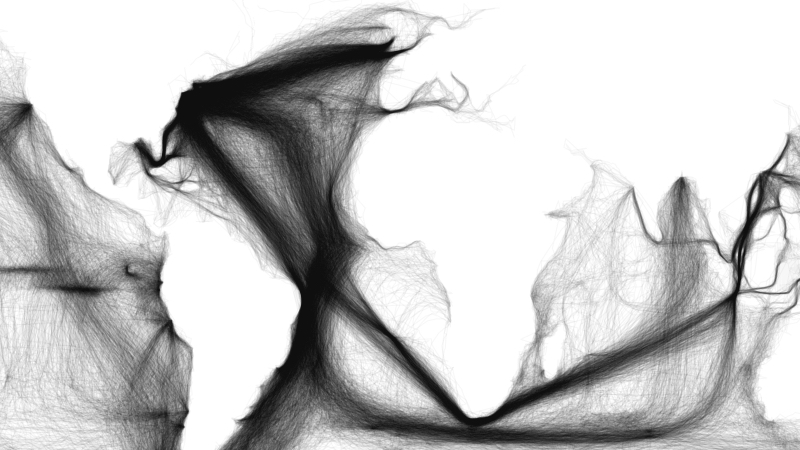

The accepted method of identifying individual humpback whales is by the unique shapes, patterns, and scars on their tails, also known as “flukes.” Until a few years ago, cetologists (that’s “whale scientists”) had to spend long hours comparing photos of flukes to find matching ones, which would constitute evidence of the movements of individual whales.

Photo-ID’ing 127,000 whales

That was before Happywhale. Founded in 2015, this is an online cetacean photo-ID platform that allows not just scientists but also tourists and other “civilians” to upload and compare pictures of whales’ tails.

Happywhale is one of those amazing Big Data success stories, with AI providing the cherry on top: So far, it has gathered more than 993,000 images from around the world from close to 350,000 encounters. Using a modified version of face recognition software, the platform has identified more than 127,000 individual whales.

This includes NA-0030, an individual spotted almost 50 years ago, in July 1975 near Newfoundland, and more recently, in March of this year, off the coast of the Dominican Republic, which is the longest time between the first and last sightings.

Another notable individual is a female known as Flame, who has been sighted 695 times over the past 20 years — more than any other humpback — mostly in the coves, bays, and inlets around Juneau, Alaska’s capital.

The database also provided a positive ID for the Colombian whale in Tanzanian waters. What scientists don’t know is why this particular individual made such a long journey.

When he was first spotted, hanging out with six other humpbacks and a group of bottlenose dolphins in Colombia’s Gulf of Tribuga in July 2013, our long-distance whale was probably already sexually mature, meaning he was at least six years old.

Stronger competition for females

The long migration to Tanzanian waters may be due to his search for a mate. Thanks to conservation efforts, global whale populations have rebounded. This also results in stronger competition for females. Humpbacks practice “male dominance polygyny,” meaning dominant males claim several females as their mates. This drives other males to search for a mate outside their usual circles.

Food may be another factor, possibly compounding the first one. Climate change has driven down stocks of krill — the small, shrimplike creatures that humpback whales feed on. This forces many to travel farther for food, and occasionally alternate between feeding grounds.

But it’s also possible that our whale simply got confused, got lost, and simply kept going. Even with one of the largest brains in the animal kingdom (an average humpback whale’s brain weighs about 4.6 kg, or 10 lb, three times the human brain), you can still occasionally do something stupid.

No whales on Kinshasa’s avenues

Here’s something else cetologists don’t know: how HW-MN1300828 got from A to B. They have photographic proof of the whale’s whereabouts in Colombian waters in 2013 and 2017, and near Tanzania in 2022, but no exact idea of his route or timing.

As this is common when identifying whale migrations based on photo evidence, the interspace between both sightings is typically expressed as the great-circle distance between both points, that is: the straight-line arc linking both points on the sphere that is the Earth.

In this case, that great-circle distance covers 120° of longitude, or one-third of the earth’s circumference. While that’s impressive, it’s also wrong, as the shortest straight line connecting points off Colombia’s Pacific coast and the Indian Ocean off Tanzania crosses several countries in the north of South America, and across Central Africa, including straight through Kinshasa. Whales are not a common sight in the avenues of the capital of DR Congo — in fact, it’s been about 50 million years since the species’ ancestors last lived on land.

The actual route followed by our horny, hungry, or possibly just confused humpback likely hugged the Pacific coast of South America, after which he swung past Patagonia to head for foraging grounds off the subantarctic islands of South Georgia and South Shetland. He then must have traveled through the Mozambique Channel, which separates Madagascar from Africa, to reach the breeding grounds off Tanzania.

Without detours and diversions, that’s a distance of easily 18,000 km (11,000 mi), or about halfway across the world. What the pictures in the Happywhale database don’t tell us is whether the long-distance wanderer found love in Zanzibar, or at least a good meal. After such a long trip, he has more than earned both.

Strange Maps #1264

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.

For more on this record-breaking migration, see: Interbreeding area movement of an adult humpback whale between the east Pacific Ocean and southwest Indian Ocean, by E. Kalashnikova e.a., published by Royal Society Open Science on 11 December 2024.

Note: Happywhale ranks HW-MN1300828’s migration as the second-longest on record. In 2023, a female humpback was spotted off Queensland in Australia, more than a decade after having been observed near Peru. The great-circle distance between both points is slightly longer, but does not require swimming around two continents, so was likely shorter in practice.