On Her Majesty’s S#*t List

Dear traveller, the Queen of England cares for your well-being. To keep you safe from harm, Her Majesty’s government has prepared 47 maps of areas around the world you should avoid.

You’ll find those maps on the website of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, along with detailed travel advice for 225 countries and territories around the world. That’s just about all of them — except the Vatican. Is Popetown so safe it requires no travel guidance whatsoever? Or would Elizabeth II rather you didn’t visit the home turf of the only other European monarch who is both a head of state and the head of a religion [1]?

The security situation in each country or territory is described briefly or more in detail, as the case warrants. Of course, the advice is aimed primarily at British travellers. The info sheet for Iran, for example, warns that “British travellers […] face greater risks than nationals of many other countries due to high levels of suspicion about the UK.” To be fair, those suspicions are grounded in decades of British meddling in Iranian affairs, culminating in the coup against Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq in 1953. So there.

But most of the FCO’s caveats hold water for non-Brits as well — provided they get their head around two contradictory mantras that crop up in nearly every advisory. On the one hand, the very British, and not entirely reassuring understatement that, “Most visits [to country X] are trouble-free.” On the other, the recurring warning about threats from terrorism [2], even in the British Antarctic Territory (where, granted, that threat is deemed to be “low”).

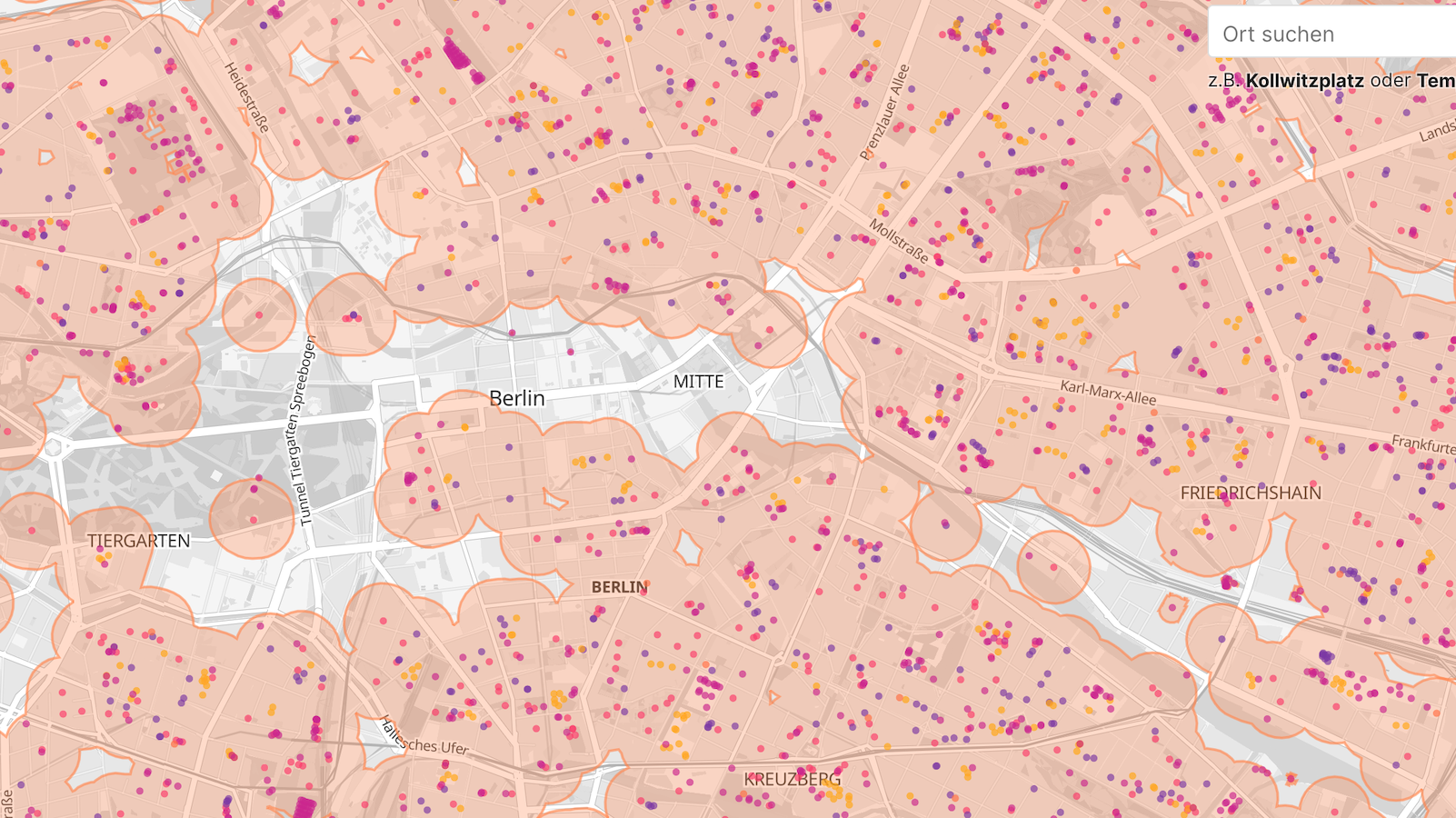

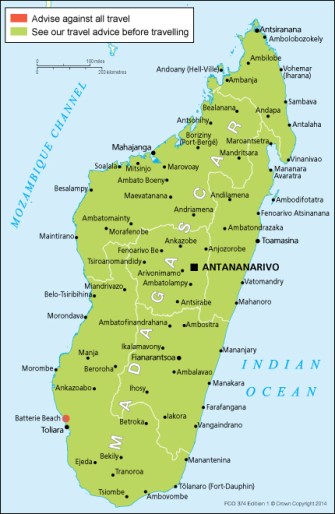

In just under 50 cases, the travel advice comes with a map, using stoplight symbolism to separate safe areas (green) from iffy zones (orange) and are-you-nuts-turn-back-now regions (red). You’d expect that list to include Israel/Palestine (treated as one area by the FCO), Ukraine or Pakistan — all countries where increased danger can be geographically defined. But no. Perhaps to avoid the diplomatic embarrassment of a “danger map” of a touchy ally?

But why then does the FCO include maps of six countries colored entirely green? Perhaps because Her Majesty wants to keep you on your toes, even before advising against “all but essential travel” (orange) or “all travel” (red) for parts of that country.

Take for example the case of all-green Mexico: “In certain parts of Mexico you should take particular care to avoid being caught up in drug-related violence between criminal groups.” Frustratingly, the Foreign Office does not tell us in which parts of Mexico it is okay to get caught up in drug-related violence between criminal groups.

Each of the green-only maps (besides Mexico: Albania, Guatemala, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, and Mozambique) comes with the warning: See our travel advice before travelling. Which is Britspeak for: Do not take your stag party here! Pretty soon, parts of these countries could turn orange or red.

As is the case for Haiti. Green all over, except for an orange dot hovering over the capital city, Port-au-Prince, where tourists are advised to avoid all but essential travel to “the Carrefour, Cité Soleil, Martissant and Bel Air neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince due to the risk of criminal activity.”

The FCO maps show six other green countries with orange zones, often in eccentric areas, away from the capital/central areas. Malaysia’s no-go zone includes only a few islands near its eastern extremity on Borneo. Bangladesh’s orange area is in that leg-like salient in the southeast, which comprises the Chittagong Hill Tracts, the security of which is a “cause for concern.”

Angola’s Orange Zone is limited to one province on the border with the DR Congo, and its exclave of Cabinda (though not the city of Cabinda itself). In Burma, orange is limited to the country’s north and to a coastal zone contingent with Bangladesh’s Chittagong area. Things look scarier in Tajikistan, where orange takes up the entire eastern half of the country, except that this is also by far the least populated part of the country.

But the most problematic map surely is that of Kenya, where not only the zone adjacent to the Somali border is colored in off-limits orange, but also a salient deep inland toward Mado Gashi, a coastal area including the port city of Mombasa, and, very specifically, the mainly Somali Eastleigh neighborhood of the capital, Nairobi — not far from Westlands, the area where the 2013 attack on the Westland shopping mall took place.

Seven countries combine a perfectly safe green zone with a red zone, where the FCO advises against all travel (not even the “essential travel” tolerated for the orange zones). These red zones are often located in lawless frontier zones, as in the case of Uganda’s border with Kenya, the northern part of Venezuela’s border with Colombia, and Djibouti’s border with Eritrea.

Other red zones are more diffuse: Burkina Faso’s northern third, not far from the capital Ouagadougou. Or the finger of unrest, creeping into Burundi from Tanzania (apart from a “classic” unstable border zone near the tripoint with Rwanda and the DR Congo). The red-green division in Western Sahara is a relic of the frozen conflict involving Morocco, which annexed the territory against the will of an indigenous resistance movement. This Polisario Front operates in the red zone beyond the wall, built by the Moroccan authorities to mark the outer limits of its effective occupation.

The most curious red zone is the single dot marking an otherwise green Madagascar: Batterie Beach, where violent attacks have led to a number of fatalities.

The meat and potatoes of the FCO map contingent are the 13 maps of countries that combine green, orange, and red zones. Like Turkey, with its resort cities on the Aegean part of the green majority of the country, but also an orange frontier zone with Syria and Iraq, turning red in the case of Syria at the border itself. North of the frontier, a single, curious orange island surrounds the city of Tunceli.

Most of the Philippines is safe, but the southern island of Mindanao, harboring an active insurgency, is divided between orange and red. Thailand is mainly green too, except for an orange area in the south, and two red flashpoints on the border with Cambodia — disputes over temple complexes straddling the border. Ecuador has the same “red” border with Colombia as does Venezuela, with an orange zone added toward the border with Peru.

Insecurity is eating up much larger parts of Algeria, Sudan, Ethiopia, Congo, and Tunisia — in a cruel irony, Tunis, site of Wednesday’s deadly terrorist attack, is lodged safely in the country’s green zone. Lebanon’s core is safely green (except for an area between Beirut and its airport), its outer layer dangerously red, both separated by an orange transition zone.

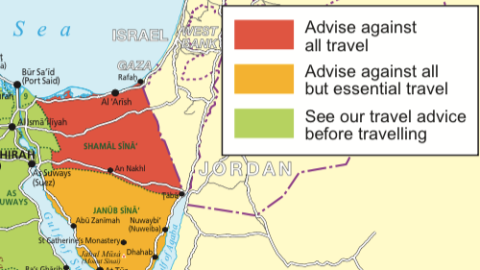

The FCO green-lights Egypt’s Nile Valley, including its capital Cairo, the Red Sea Coast, the Sharm el Sheikh resort, and a strip covering almost all of Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, plus a curious poke all the way to the Siwah oasis, close to the Libyan border. The Saharan west and the south of the Sinai Peninsula are orange; northern Sinai, bordering Israel and Gaza, and the site of numerous terrorist attacks, is red as blood.

Russia’s red and orange zones are concentrated in the Caucasus, with Chechnya and Dagestan fiery red, while the neighboring republics toward Sochi are orange. Just to the south is Georgia, with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, regions whose independence is recognized and guaranteed by Russia, marked in red — the transition zone with unoccupied Georgia marked in orange.

Next up are eight countries you’d better have a good reason to visit — all orange and red. For some, however, not being entirely red actually constitutes progress. Like the orange circles enveloping the cities of Berbera and Hargeysa in northern Somalia (the latter the capital of the self-declared, unrecognized state of Somaliland). Or the fact that large parts of Afghanistan and Iraq are “merely” orange.

Mali, Mauritania, and Niger resemble each other: the color red covering the large, empty interior of northern Africa’s Sahara desert. The DR Congo’s red zone, extending across the north and especially the east of the country, marks a zone that has been restive ever since the death of Mobutu in 1997 and could be slipping permanently beyond the control of Kinshasa, far away to the west. Iran is orange, except for its red borders — a thin line with Iraq, a thick one with Afghanistan, and a deep zone of unrest where it straddles Balochi areas in Iran and Pakistan.

Three West African countries constitute a special case: entirely orange, but for the Ebola virus Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea probably would be totally green. And if the deadly disease is defeated or at least successfully contained, they could soon be again.

Such a fate seems harder to imagine for the countries on Her Majesty’s Shit List, colored entirely red and to be avoided like the plague: Yemen, Syria, Libya, and South Sudan. Currently subjected to high levels of insecurity, violence, and bloodshed, they remain unlikelier destinations for travellers of leisure (British or otherwise) than even Somalia, Iraq, or DR Congo.

But surely one day, an anonymous official at the FCO’s imposing offices at Whitehall will savor the satisfaction of reversing the tide of red on these maps, marking cities and regions first orange, then green. In any case, it will be a while yet before any of those countries now marked red will get a visit by the FCO’s most valued tourist of all, Queen Elizabeth II herself.

For the entire list, see the FCO Travel Advice web page. Images under Crown Copyright, reproduced under the terms of the Open Government Licence as described at the FCO website.

Strange Maps #706

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected]

[1] QE2 is of course Queen of England (or more precisely: the United Kingdom) and several other countries (including Canada, Australia and Pakistan), but also the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. The Pope is both the head of the Catholic Church, and the head of state of Vatican City (see also #601). A more recent theocracy is Islamic State, led by a Caliph who also wields both temporal and spiritual power.

[2] The threat from terrorism can be “low” (as in Papua New Guinea), “general” (as in Peru), “underlying” (as in Oman) or “high” (as in Niger, or France).