How Atlantic City inspired the Monopoly board

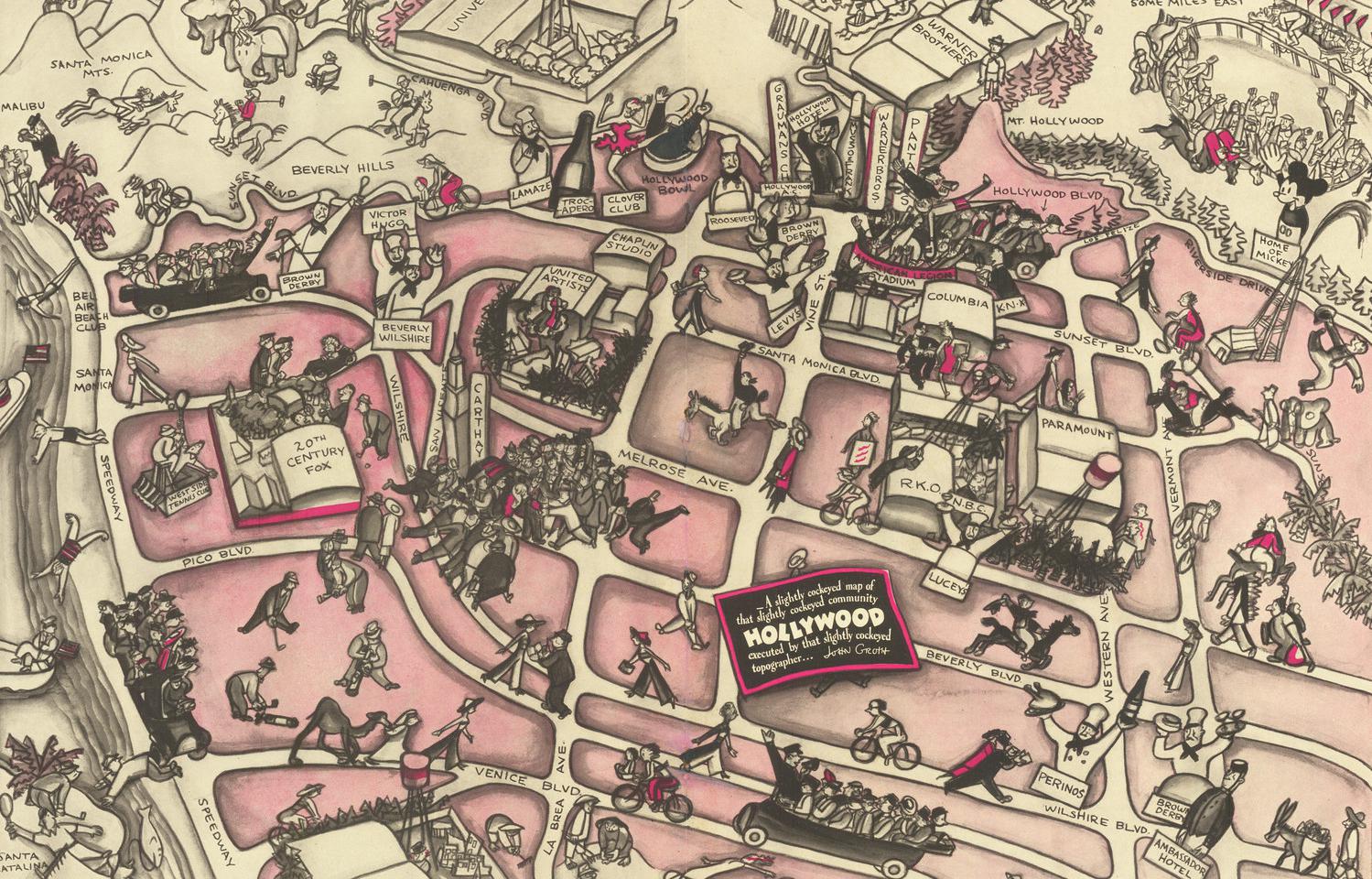

Credit: Davis DeBard, with kind permission.

- The streets on a classic Monopoly board were lifted from Atlantic City.

- Here’s what it looks like if we transport those places back onto a map.

- Monopoly started out as its opposite: a game explaining the evil of monopolies.

There have been several attempts to turn Monopoly the game into a Hollywood movie, one with Ridley Scott directing, another starring Kevin Hart. If none have succeeded so far, it’s not for lack of an exciting backstory.

Dig deep, and you’ll find racial segregation, economic inequality, intellectual property theft, and outlandish political theories. But let’s start with the board—a map of sorts and a story in itself.

There’s a customized Monopoly board not just for virtually any country in the world but also for movie and TV franchises (Avengers, Game of Thrones), brand experiences (Coca-Cola, Harley Davidson) and just about anything else (bass fishing, chocolate, the Grateful Dead).

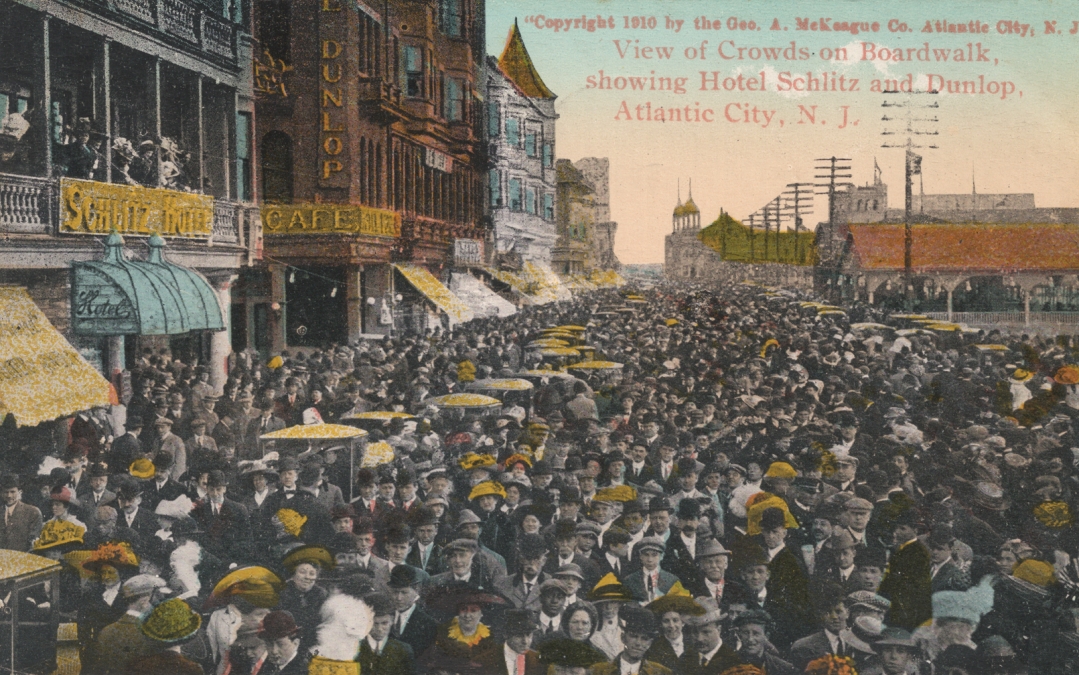

To aficionados of the game, however, the names of the streets on the “classic” board have that special quality of authenticity, from lowly Baltic Avenue to fancy Park Place. Those places sound familiar not just if you like Monopoly, but also if you drive around Atlantic City, New Jersey’s slightly run-down seaside casino town.

In fact, all the street names were taken from (or near) the city once nicknamed “America’s Playground.” Going about town, it’s almost like you’re traveling on the board itself. No wonder its other nickname is “Monopoly City.”

This map transposes the streets on the board back onto the map, maintaining the color scheme that groups them from cheap (dark purple) to expensive (dark blue). Here’s how they run.

Dark purple

Mediterranean Avenue and Baltic Avenue are parallel streets in the middle of town, running southwest to northeast. They are perpendicular to most other streets on the board, and as such, cross or touch five other colors.

Light blue

Three avenues in the east of town. Oriental runs southwest to northeast and crosses Vermont and Connecticut, which run parallel to each other.

Light purple

Three streets branching off Pacific Avenue: Virginia Avenue, a long street towards the northwest; and St. Charles Place and States Avenue, two short spurs towards the southeast. St. Charles Place is no more; it made way for a hotel-casino called the Showboat Atlantic City.

Orange

New York and Tennessee Avenues run parallel and next to each other, northwest to southeast, the former all the way to the Boardwalk. St. James Place is in between both, south of Pacific Avenue.

Red

Indiana, Kentucky, and Illinois Avenues are the furthest west of the five street groups running northwest to southeast. In the 1980s, Illinois Avenue was renamed Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard.

Yellow

Past O’Donnell Memorial Park—featuring a rotunda dedicated to Atlantic City’s World War I soldiers—Atlantic Avenue continues west to Ventnor City as Ventnor Avenue. It is pictured as an inset (left) on this map, which also features Marvin Gardens. That place, in Margate City, is actually spelled Marven Gardens—an error for which Parker Brothers apologized to the local residents only in 1995.

Green

These opulent streets are well-connected in more than one sense. Green is the only color to touch every other color.

Dark blue

The Boardwalk is as huge as Park Place is diminutive. Both are close to the beachfront, the most desirable location in any seaside resort.

The darker history of Monopoly

These names weren’t picked at random. In the early 1930s, various informal versions of Monopoly were played throughout the northeastern United States, with local street names inserted for each city. The game’s appearance and rules were perfected as it was being played. Around that time, an Atlantic City realtor named Jesse Railford hit upon an innovation: to put not just names but also prices on the properties on the board. Since he knew the lay of the land in his home city, those prices reflected the hierarchy of real estate values at that time.

That hierarchy and those prices were informed by the segregation that was rife in 1930s America. As one of the gateways of the Great Migration in the early 20th century, Atlantic City was a waystation for countless African-Americans leaving behind the stifling oppression of the South for better economic opportunities in the North. However, what they encountered on the way and upon arrival was the same racism, in slightly different form.

Railford played the game with the Harveys, who lived on Pennsylvania Avenue. They had previously lived on Ventnor Avenue and had friends on Park Place—all of which fall into the pricier color categories on the board.

In 1930s Atlantic City, these were wealthy and exclusive areas, and “exclusive” also meant no Black residents. They lived in low-cost areas like Mediterranean and Baltic Avenues; the latter street is actually where the Harveys’ maid called home. In many local hotels at the time, African-Americans were only welcome as workers, not as guests. Atlantic City schools and beaches were segregated.

Belying both the binary prejudices of the time and the sliding price scale of the Monopoly board, Atlantic City back then was in fact a place of opportunity where a diverse range of communities flourished. Black businesses thrived on Kentucky Avenue. Count Basie played the Paradise Club on Illinois Avenue. There was a Black beach at the end of Indiana Avenue. For Chinese restaurants and Jewish delis, people headed to Oriental Avenue. New York Avenue had some of the first gay bars in the U.S.

It should have been called “Anti-Monopoly”

An Atlantic City-based board was sold to Parker Brothers by Charles Darrow, who claimed to have invented the game in his basement. Parker Brothers marketed the game as Monopoly from 1935. The rights to the game transferred to Hasbro when it acquired Parker Brothers in 1991.

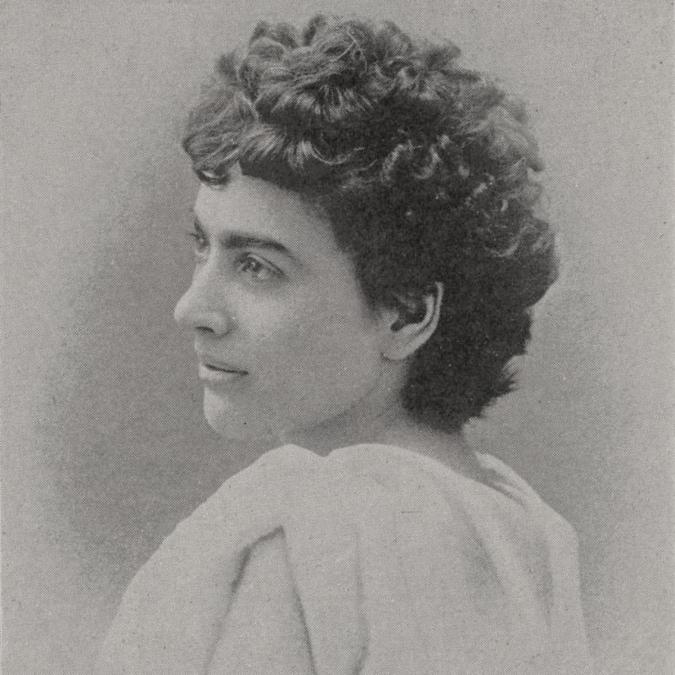

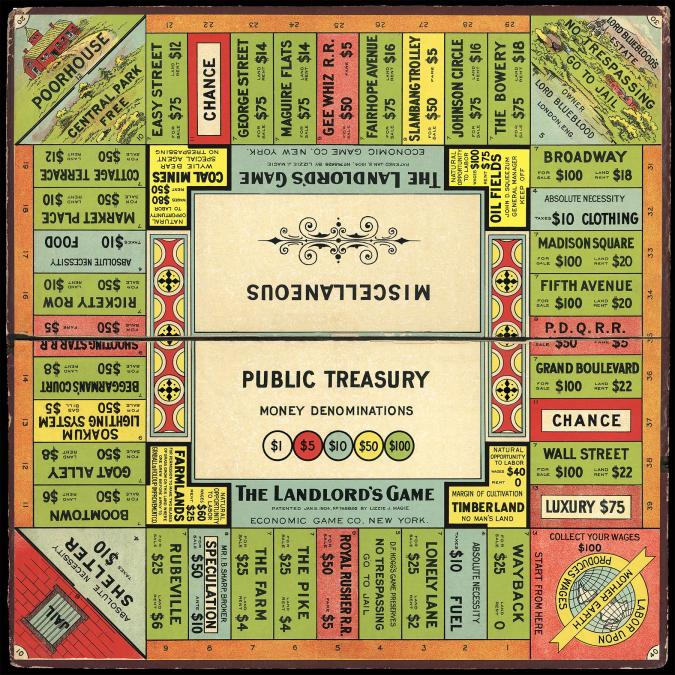

But Darrow didn’t invent Monopoly. The original idea, as became widely known only decades after its “official” launch, came from Lizzie Magie (1866-1948), née Elizabeth J. Phillips.

Magie was a woman of many talents and trades. She worked as a stenographer, a typist, and a news reporter; she wrote poems and short stories; she was a comedian, an actress, and a feminist (she once published an ad to auction herself off as a “young woman American slave,” to make the point that only white men were truly free); and she patented an invention that made typewriting easier.

Despite that impressive resume, she is now remembered mainly—and barely so—as the inventor of Monopoly. Except that the board game she developed was called The Landlord’s Game. She patented it in 1904 and re-patented a revised version in 1924. The game was innovative because of its circular pattern—most board games at the time were linear. But its real point was economic, political, and ultimately, fiscal. The Landlord’s Game illustrated Magie’s belief in what was later called Georgism.

Known as the “single tax movement” and popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, its concepts were formulated by the economist Henry George. He suggested that rather than taxing labor, trade, or sales, governments should derive their funding only from taxing land and the natural resources that derive from it.

As already observed by earlier thinkers such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo, a land tax is economically more efficient than other taxes, since it places no burden on economic activity. It would also reduce property speculation, eliminate boom and bust cycles, and even out economic inequality.

Although Georgist ideas were influential for a while and continue to be discussed—among others by Ralph Nader during his 2004 presidential candidacy—they are no longer a vital political force, except in the related field of emissions trading. One popular counterargument to modern Georgism, now also (but not entirely interchangeably) known as “geoism,” “geolibertarianism,” and “earth-sharing,” is that government expenditure has increased by so much since George’s day that it can no longer be covered by a land tax alone.

Back around the turn of the 20th century, Magie devised The Landlord’s Game to educate its players about the evils of real estate monopolies and, implicitly, about the benefits of a single tax on land.

She created two sets of rules: an anti-monopolist one, called Prosperity, in which all were rewarded for any wealth created; and a monopolist one, called Monopoly, in which the aim was to crush one’s opponents by creating monopolies. In the latter version, when a player owns all the streets of one color, they can charge double rent and erect houses and hotels on the properties.

Taken together, these two versions were meant to illustrate the evil of monopolies and the benefit of a more cooperative approach to wealth creation. It’s very telling of human nature that it’s the opponent-crushing version that came out the winner. But, in the light of what happened to Magie, perhaps not entirely surprising.

When Darrow claimed Monopoly as his own, Magie protested. In the end, her patent was bought out by Parker Brothers for a mere $500, without any residual earnings. Parker Brothers continued to acknowledge Darrow as the inventor of the game. Magie’s role was not recognised until decades later.

For more on the intersection of Monopoly, Atlantic City geography and 1930s segregation, read this article in The Atlantic by Mary Pilon. She is also the author of a book on the subject, called The Monopolists.

Many thanks to Robert Capiot for alerting me to the article. And many thanks to mapmaker Davis DeBard for permitting the use of his work. Follow him here.

Strange Maps #1078

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and on Facebook.