China’s most important border is imaginary: the Hu Line

Credit: Tomaatje12, CC0 1.0 – Public domain.

- In 1935, demographer Hu Huanyong drew a line across a map of China.

- The ‘Hu Line’ illustrated a remarkable divide in China’s population distribution.

- That divide remains relevant, not just for China’s present but also for its future.

A bather in Blagoveshchensk, on the Russian bank of the Amur. Across the river: the Chinese city of Heihe.Credit: Dimitar Dilkoff/AFP via Getty Images

The Hu Line is arguably the most consequential feature of China’s geography, with demographic, economic, cultural, and political implications for the country’s past, present, and future. Yet you won’t find it on any official map of China, nor on the actual terrain of the People’s Republic itself.

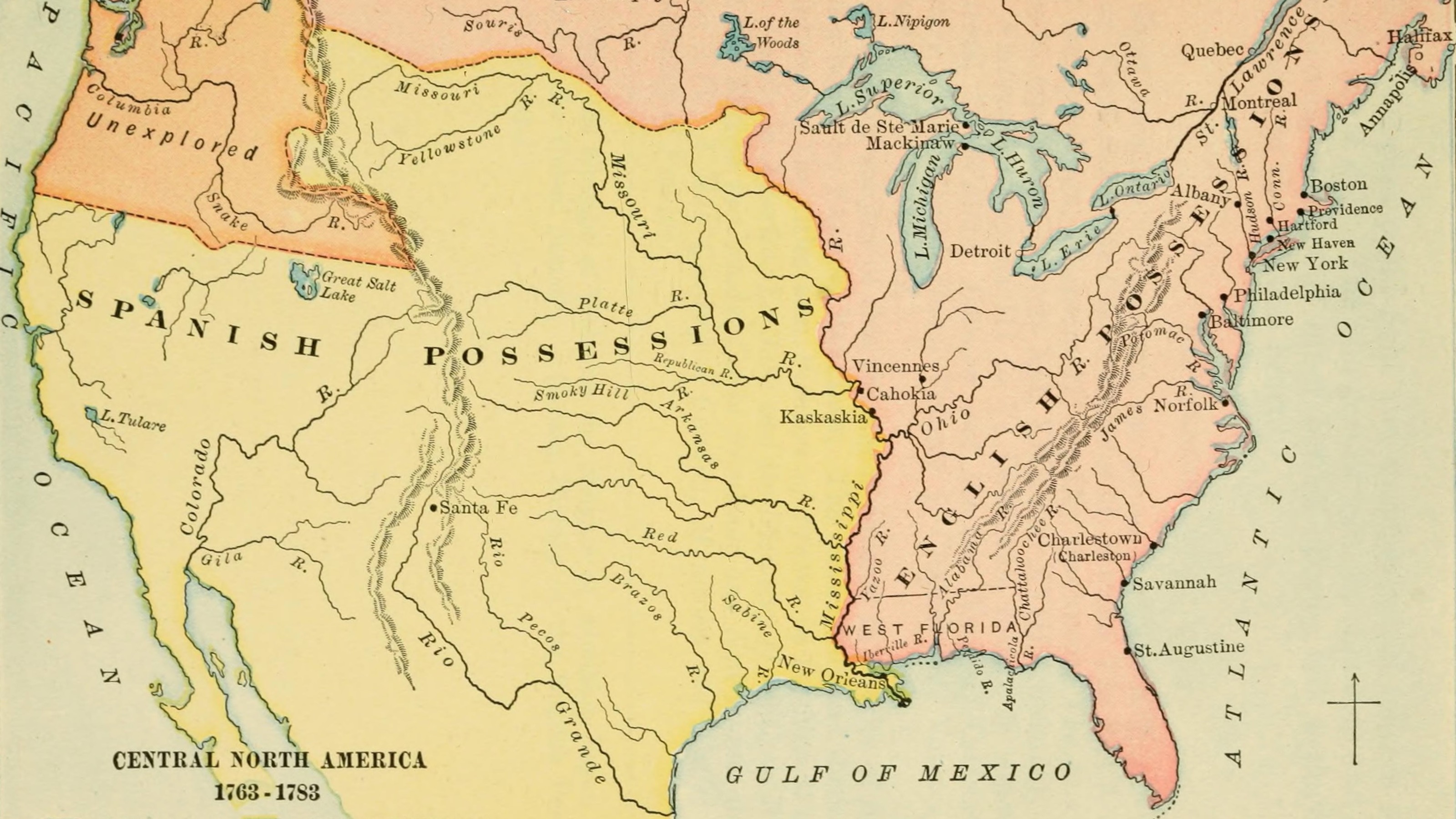

There are no monuments at its endpoints: not in Heihe in the north, just an icy swim across the Amur from Blagoveshchensk, in Russia’s Far East; nor in Tengchong, the subtropical southern city set among the hills rolling into Myanmar. Nor indeed anywhere on the 2,330-mile (3,750-km) diagonal that connects both dots. The Hu Line is as invisible as it is imaginary.

Yet the point that the Hu Line makes is as relevant as when it was first imagined. Back in 1935, a Chinese demographer called Hu Huanyong used a hand-drawn map of the line to illustrate his article on ‘The Distribution of China’s Population’ in the Chinese Journal of Geography.

The point of the article, and of the map: China’s population is distributed unevenly, and not just a little, but a lot. Like, a lot.

- The area to the west of the line comprised 64 percent of China’s territory but contained only 4 percent of the country’s population.

- Inversely, 96 percent of the Chinese lived east of the ‘geo-demographic demarcation line’, as Hu called it, on just 36 percent of the land.

Much has changed in China in the intervening near-century. The weak post-imperial republic is now a highly centralized world power. Its population has nearly tripled, from around 500 million to almost 1.4 billion. But the fundamentals of the imbalance have remained virtually the same.

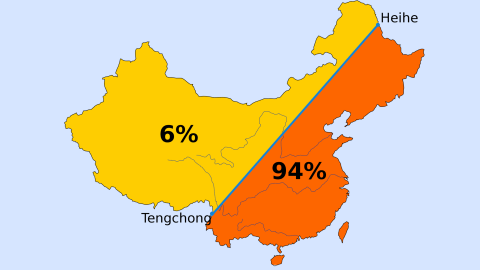

Even if China’s territory has not: in 1946, China recognized the independence of Mongolia, shrinking the area west of the Hu Line. Still, in 2015, the distribution was as follows:

- West of the line, 6 percent of the population on 57 percent of the territory (average population density: 39.6 inhabitants per square mile (15.3/km2).

- East of the line, 94 percent of the population on 43 percent of the territory (average population density: 815.3 inhabitants per square mile (314.8/km2).

Hu Huanyong’s original hand-drawn map of China, showing population density and the now-famous line (enhanced for visibility).Credit: Chinese Journal of Geography (1935) – public domain.

Why is this demographic dichotomy so persistent? In two words: climate and terrain. East of the line, the land is flatter and wetter, meaning it’s easier to farm, hence easier to produce enough food for an ever-larger population. West of the line: deserts, mountains, and plateaus. Much harsher terrain with a drier climate to boot, making it much harder to sustain large amounts of people.

And where the people are, all the rest follows. East of the line is virtually all of China’s infrastructure and economy. At night, satellites see the area to the east twinkle with lantern-like strings of light, while the west is a blanket of near total darkness, only occasionally pierced by signs of life. In China’s ‘Wild West’, per-capita GDP is 15 percent lower on average than in the industrious east.

An additional factor typifies China’s population divide: while the country overall is ethnically very homogenous – 92 percent are Han Chinese – most of the 8 percent that make up China’s ethnic minorities live west of the line. This is notably the case in Tibet and Xinjiang, two nominally autonomous regions with non-Han ethnic majorities.

This combination of economic and ethnic imbalances means the Hu Line is not just a persistent quirk, but a potential problem – at least from Beijing’s perspective. Culturally and geographically distant from the country’s east, Tibetans and Uyghurs have registered strong opposition to China’s centralizing tendencies, often resulting in heavy-handed repression.

Street view in Tengchong, on China’s border with Myanmar. Credit: China Photos/Getty Images

But repression is not the central government’s long-term strategy. Its plan is to pacify by progress. China’s ‘Manifest Destiny’ has a name. In 1999, Jiang Zemin, then Secretary-General of the Chinese Communist Party, launched the ‘Develop the West’ campaign. The idea behind the slogan retains its political currency. In the last decade, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang has repeatedly urged the country to “break through” the Hu Line, in order to modernize China’s western half.

The development strategy has an economic angle – adding industry and infrastructure to raise the region’s per-capita GDP to the nation’s average. But the locals fear that progress will bring population change: an influx of enough internal migrants from the east to tip the local ethnic balance to their disadvantage.

China’s ethnic minorities are officially recognized and enjoy certain rights; however, if they become minorities in their own regions, those will mean little more than the right to perform folklore songs and dances. The Soviets were past masters in this technique.

Will China follow the same path? That question will be answered if and when the Hu Line fades from relevance, by how much of the west’s ethnic diversity will have been sacrificed for economic progress.

Strange Maps #1071

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.