Too loud? In Japan, they’ll map-shame you

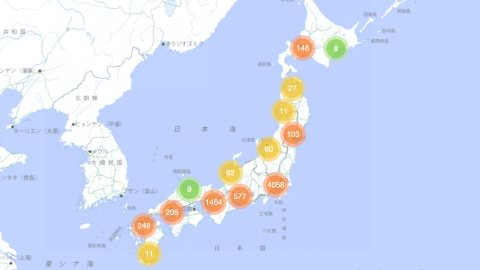

Credit: DQN Today

- Highly urbanized, Japan is the noisiest country on Earth, and it’s driving people to extremes.

- Extremes like reporting their neighbors to a website that has mapped 6,000 public nuisance hot spots.

- But who are the real anti-social actors here: the noisy children or the people reporting them?

Kinkaku-ji, the beautiful and serene ‘Temple of the Golden Pavilion’ in Kyoto. Not what everyday life in Japan looks (or sounds) like. Credit: Henry Ngo, CC BY 3.0

Think of Japan and you may dream of serene temples and quiet gardens. Of meditative introspection in an ocean of silence. Shows how much you know.

Japan is one of the most urbanized countries in the world: 92 percent live in cities. Most Japanese spend their days blanketed in an omnipresent and near-constant cloud of ambient urban noise.

Japan has a culture of constant public announcements, both official, commercial and (at least in election season) political. In fact, a 2018 report by the World Health Organization found that Japan was the noisiest country in the world.

One oft-cited example: due in part to the barrage of electrically amplified messages, busy Tokyo train stations such as Ueno and Tameike-Sanno generate a noise level of about 100 decibels, which is almost double the WHO’s recommended limit (53 dB).

With levels of noise pollution constant and high, peace and quiet are a rare and fleeting commodity for most Japanese. With that in mind, a phenomenon like dorozoku starts to make sense.

‘Dorozoku’ literally translates as ‘street tribe’, but it has come to denote a particular kind of person: the kind who obstructs free passage, talks loudly and, in general, is a public nuisance, flaunting the inalienable right of everybody not to be bothered by everybody else.

The term was popularized by DQN Today, a website that crowd-sources reports of noise pollution and other examples of close-quarter grievances, purportedly helping prospective house hunters to avoid neighborhoods plagued by playful children and overly talkative adults.

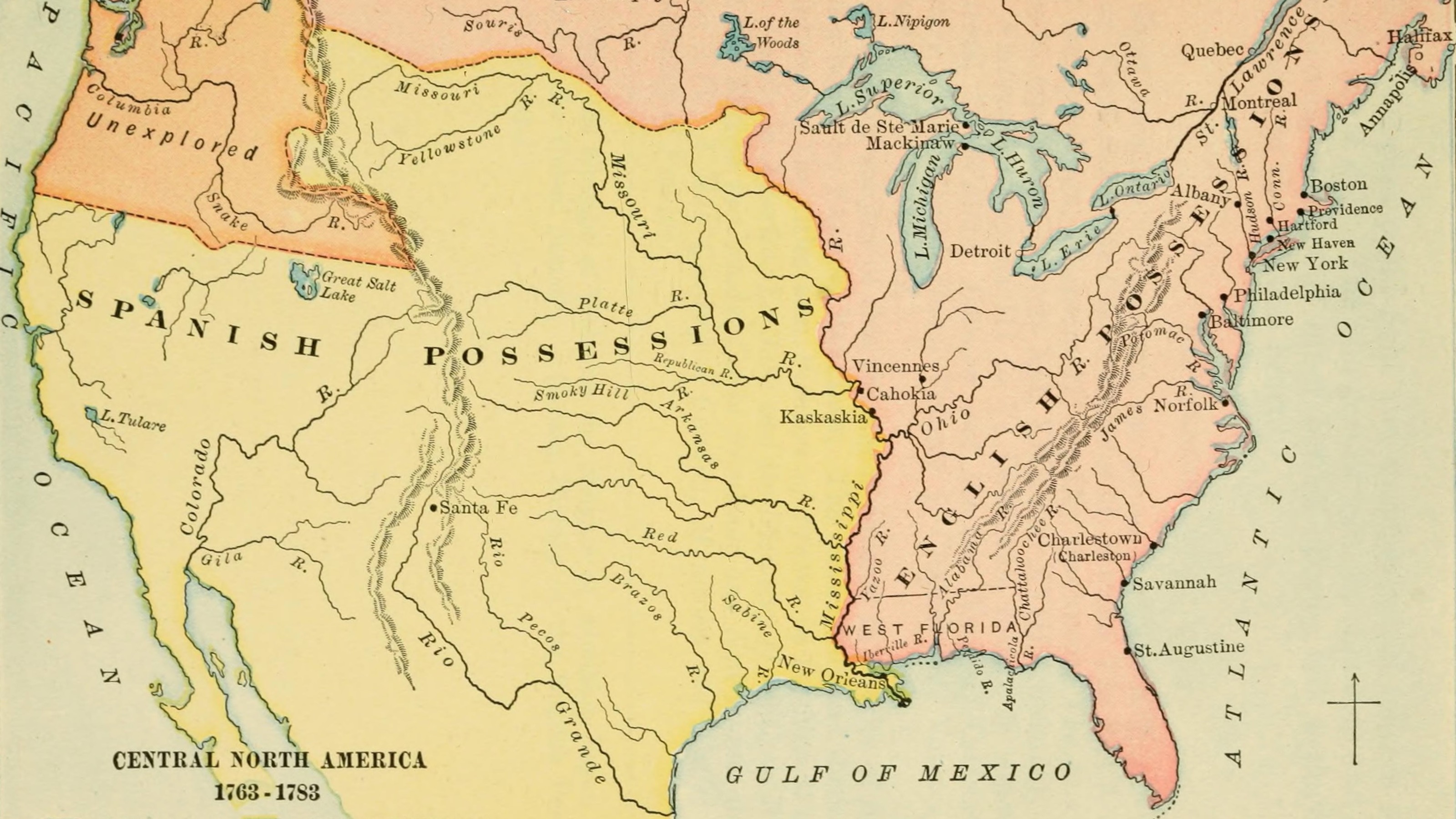

The bigger the city, the more complaints; and most of all in Tokyo – a megacity of more than 37 million.Credit: DQN Today

Each grievance is pinned to an interactive map of Japan. Zoom in on the dorozoku map, and the country comes alive in a riot of icons and colours, each showing particular types of noise pollution. In all, close to 6,000 noise hotspots are listed, all reported and described by disgruntled locals.

The map was started back in 2016 by a Yokohama resident, who prefers to remain anonymous. The forty-something systems developer, who works from home, was prompted by a bunch of noisy children hanging around his house, messing with his concentration. He wanted the map to help other people avoid moving into noisy neighborhoods like his.

The webmaster reviews all reports submitted to the website and filters out about one in ten, because of personal, slanderous or potentially malicious content (e.g. “Only girls in this area”). He also, though more rarely, receives requests to take down reports because the issue has been resolved.

Although they probably lose something in (Google) translation, the complaints make for fascinating reading. Some examples:

Near Kashiwazaki, in the otherwise rather quiet prefecture of Niigata on the western shore of Honshu.

Annoying

The voice of a kid living in a

residential area around here

is not noisy; it’s like a monkey

in a zoo that is always making

noise with a strange voice.

In Hadokate, a port city near the southern tip of Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost island, it’s not just sounds that offend but smells as well.

Moral hazard

There are many households

that roast meat even though

the space between houses is small,

and on a clear day, it smells

like roasted meat in the town.

Japan’s southernmost complaint comes from the small island city of Ishigaki.

Why do you get together in the evening

Whatever the day is, multiple families

With children gather around 5 pm

To ride bikes, ring the bell loudly, play ball

And make strange noises in the parking lot.

Parents chat by the window, and children

Play on the stairs as an athletic substitute.

Tokyo is teeming with complaints. Here’s just one.

Back road of shopping street

Parent-child baseball metal bat noise

and catch ball noise in a dead-end

The voice of the family who whispers it

Strange voice etcetera.

Even smaller places, like Kashiwazaki in Niigata prefecture, have their share of complaints.Credit: DQN Today

Initially relatively small and unnoticed, the website has gone on to nationwide success, especially since the start of the pandemic a year ago. Overall noise complaints have increased significantly in Japan (+30 percent in Tokyo) since everybody–and their kids–has been stuck at home. And the number of complaints to the dorozoku website has shot up by thousands since last year.

And it seems Japan’s thirst for quietude is colliding with one source of noise in particular – not traffic, station announcements, or shop music, but children (1).

With notoriety came controversy. While most observers would agree the map is a symptom of Japan’s changing attitude towards children, some see it as part of the solution, others as part of the problem.

One pro-map argument goes like this: Japan is no longer as deferential a society as it once was. Where once parents would respond to criticism of their children’s behaviour by disciplining them, they are now likely to direct their anger at those who complain, rather than those complained about. The online map is a non-confrontational way to vent frustration and call attention to the problem.

Crowds at Ueno station, where noise is at double the level recommended by the WHO.

Credit: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP via Getty Images

A counterargument: Japan has a particularly thin-skinned attitude towards children’s noise. Women who carry noisy babies on public transport have been known to receive vocal, harsh criticism for it. In 2012, residents near a daycare centre demanded that it reduce its noise levels, citing a bylaw banning noise over 45 decibels. In 2014, the bylaw was adapted to exempt younger children.

So, while the map can be seen as a repertory of anti-social behaviour, a case could be made that the real anti-socials are not the ‘street tribes’, but the ones who feel compelled to report them.

In the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, Norihisa Hashimoto, a professor emeritus of acoustic engineering, pointed out that whether noise is irritating depends not just on the noise, but also on the listener – more specifically on their current mood and general degree of social isolation; both of which are likely to have worsened due to the coronavirus. People who complain may feel they’re reasonable, but they could actually be fueling intolerance, he said.

Kids at play are noisy. And so are neighborhoods and streets bustling with life. Could it be that the dorozoku map is an expression not of rising levels of noise pollution, but instead of lowering levels of tolerance for what could be construed as ‘normal’ street noise?

A final factor, and perhaps a decisive one: Japan is experiencing a demographic bust. Reversing that would actually require a higher level of tolerance for youthful exuberance. Instead, dorozoku looks like a symptom of an aging society, irritably requesting that the young’uns “turn the damn volume down” and “get off that lawn.”

Many thanks to Jeremy Hoogmartens for sending in this map. Images found at DQN Today.

Strange Maps #1072

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) To be fair: not just children. The New York Times reported a recent case of a construction worker stabbed to death in his parents’ Tokyo apartment by an older resident in the same building, who told police “he couldn’t stand the loud footsteps and voices”.