Beware of Ronnies (and Other Lessons from the German Election)

If you find yourself in the southern part of East Germany and in the company of several guys called Ronny, chances are you’re attending a meeting of Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), the right-wing party that scored almost 13% in the 2017 German parliamentary elections.

Angela Merkel’s CDU (and its Bavarian sister party CSU) won 33% of the vote on September 24th, down 8% since the previous parliamentary election but enough to remain the largest grouping in the Bundestag – and for Ms. Merkel to have a shot at a fourth term as Chancellor – although coalition talks have broken down, and as of early December, the chances that Merkel will continue as Chancellor appear to be slimming.

The social-democratic SPD managed just 20% of the vote, down almost 6% since last time. For both formations, these were the worst results since 1949. Biggest winners were AfD, who shot up from just under 5% to 12.7%. Previously unrepresented in the Bundestag (the voting threshold is 5%), they will now have 94 representatives. Not only is AfD the first openly right-wing nationalist party to gain seats in the German federal parliament, they are now bigger than the Liberal, Left and Green parties.

AfD did particularly well in deprived parts of eastern Germany, especially the south and east. As these two maps show, there is a large degree of correlation between the prevalence of the first name ‘Ronny’ (yellow dots on the map left) and areas where AfD got the largest share of votes (darker blue on the map right). Of course, correlation is not causation: being a Ronny doesn’t predetermine you to vote for right-wing parties; nor does such voting behaviour necessarily mean you become a Ronny.

The shadings and colours on electoral maps are as changeable as the whim of the electorate, but sometimes they eerily echo other maps and image. Previous examples discussed on this blog include the persistence of the old border between the German and Russian empires on the Polish electoral map (see #348), the resurrection of East Germany on a map of the 2013 Bundestag elections (#626) and even the similarity between David Cameron’s 2015 general election victory map of the UK and Maggie Simpson (#712).

As suggested by these examples, some correlations may indeed be connected, while other connections are completely fanciful. It’s not entirely certain into which category the link between an abundance of Ronnies and the electoral success of AfD falls.

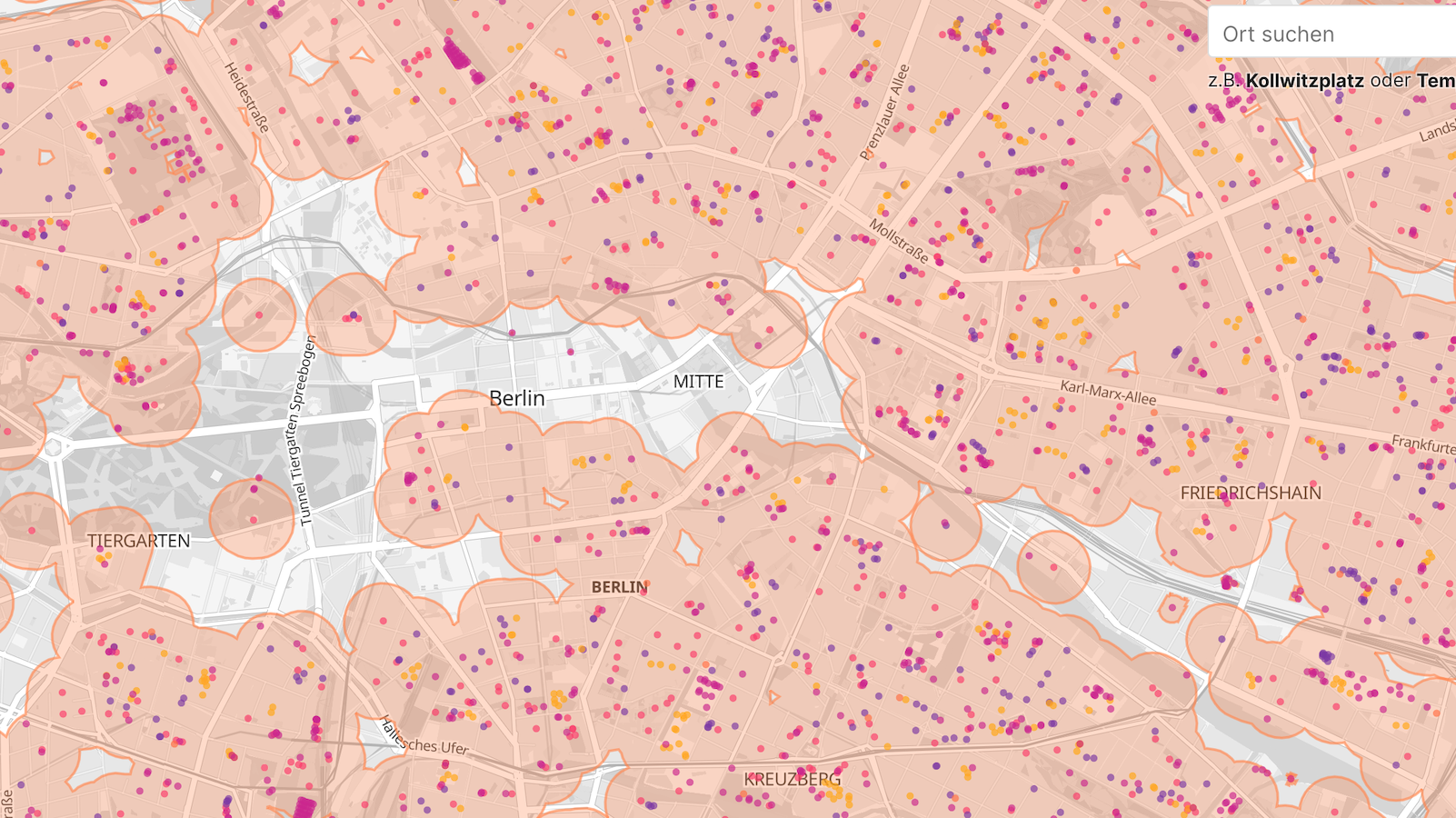

Fortunately, there’s more German electoral map goodness to be had. The German weekly Der Spiegel produced a number of maps redrawing Germany as a set of electoral archipelagos, in the style of a New York Times map on the divisive outcome of the last U.S. presidential election (see also #810).

Each of the six maps is a scenario for coalition government, and shows in which electoral districts the parties needed to form that government have a majority. Only the first two of these scenarios also command an overall majority in the Bundestag – a pointed reminder of the limited room for maneuver that Merkel (or her successor) has.

The symbols below each map show some vital statistics of each of these ‘countries’, left to right: population, unemployment rate, share of Christians, share of inhabitants qualified to enter higher education, and net per-capita income.

The first scenario is the ‘Jamaica Republic’, so called because the colours of the parties necessary to form this coalition match those on the Jamaican flag: the christian-democrat CDU/CSU formation (black), the liberal FDP (yellow), and B90/Die Grüne (green). This is mathematically possible, as the three parties together command a majority in the Bundestag. However, as shown by this map of electoral districts with a ‘Jamaican’ majority, this would be an exclusively West German government, as well as leaving out large chunks of central Germany.

‘GroKo’ stands for Große Koalition, or Grand Coalition – a government of the two largest parties, CDU/CSU and SPD. However, following its historical defeat, the SPD has announced that it would prefer to go into opposition, making the Jamaica outcome more likely. A GroKo Republic, consisting of the electoral districts where both GroKo parties hung on to their joint majority, comprises almost the entirety of former West Germany, and a good half of former East Germany.

Ideologically, a Black/Yellow Republic makes more sense than a tripartite coalition with the Greens, but CDU/CSU and FDP together garnered less than 50% of the vote; it is unlikely that Merkel would want to lead a minority government, dependent on the support of parties outside her coalition. The Black/Yellow Republic shown here consists of the electoral districts where christian-democrats and liberals did manage to get at least half of the votes: a solid block in the south, a less solid block in the north; in all, about half of the old West Germany.

A Schwarze Republik – a Black Republic – is even less likely: as shown by this map, the areas where either CDU or CSU have managed to gain a majority on their own are few and far between – and none of them in major urban centres: Meppen and Borken in the northwest, and Weiden and Straubing in Bavaria. It is, in concordance with the political leaning of the CDU/CSU, the most Christian of the six republics shown here (and almost doubly so as the Red-Red-Green Republic).

An alliance of the other side of the political spectrum would look like this on the map. This Red-Red-Green Republic would require the SPD to work together not just with B90/Die Grüne (a left-green alliance) but also with Die Linke (the Left Party), a formation further to the left of the SPD. However, this coalition does not command a parliamentary majority either, limited as it is to a small number of urban islands throughout Germany: Kiel, Bremen, Göttingen, Dortmund, Aachen, Saarbrücken, Freiburg, and last (but not least) Berlin.

How about an Ampel-Republik, a Traffic-Light Republic? This country would consist of electoral districts where the SPD (red), the FDP (yellow) and B90/Die Grüne (green) together achieved at least 50% of the vote. But the electoral mathematics (and map) falls short for this option as well. Ampel-Land consists of a small, disparate archipelago of city-islands, scattered from Lübeck and Oldenburg in the north over Münster, Cologne, Frankfurt and Göttingen in the centre to Freiburg and a small area to the north of München in the south.

Many thanks to Renke for sending in the article, found here in Der Spiegel.

Strange Maps #860

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].