Pandemic resurrects old Australian border dispute

Image: Google Earth & Ruland Kolen

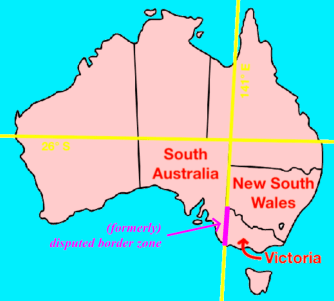

- A 19th-century surveying error created a complicated tripoint on the Murray River in eastern Australia.

- Officially, the dispute about the zigzag border between South Australia and Victoria was settled in 1914.

- COVID-19 is making life so difficult for the locals that now they want to switch sides again.

Sunset in South Australia’s Riverland, close to the zigzag border with Victoria and New South Wales.Image: Yuri Obst – CC BY-SA4.0

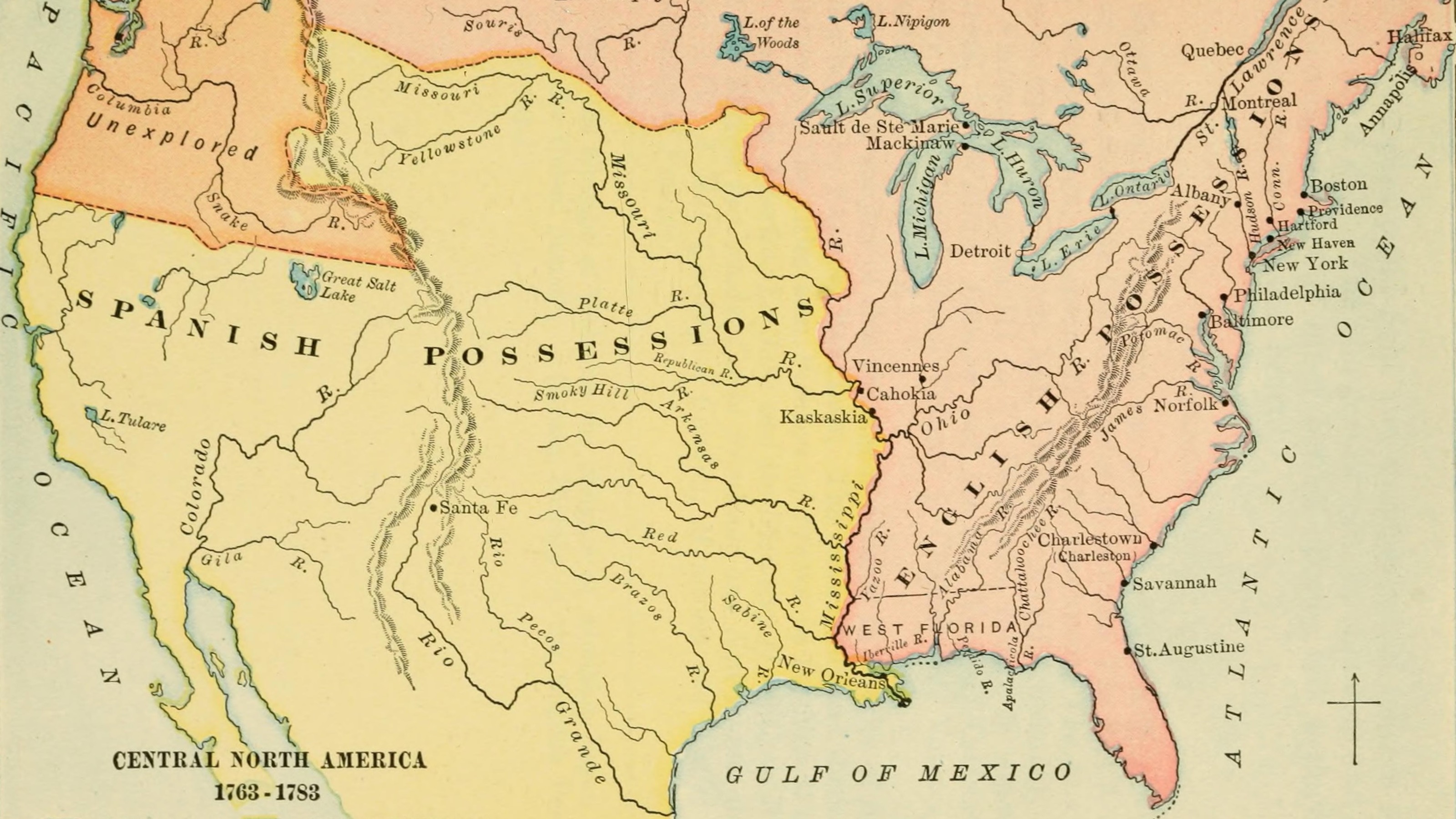

South Australia’s eastern border looks like one of those unswervingly straight lines that zip through deserts and other thinly settled parts of the world without the slightest deviation. And indeed, it starts at the 26th parallel as it ends 833 miles further south, on the sandy shores of the Southern Ocean: straight as an arrow.

But swerve it does. Zoom in on the place where that border meets the Murray. That mighty river flows into South Australia from the east, where it forms the border between New South Wales (NSW) to the north, and Victoria to the south. Here, South Australia’s eastern border hitches a ride of about three miles downstream before it resumes its southward plunge.

The result is a zigzag border – a wonderful anomaly, if you’re into that kind of thing. But if you’re local, that border is nothing but trouble. And with the coronavirus further complicating things, many now want the anomaly gone. Quite a few local Victorians want the border drawn as was intended by South Australia’s founding document, almost two centuries ago. That would make them citizens of South Australia, the state where they do most of their business anyway.

In 1836, the Letters Patent that established what was initially known as the colony of South Australia declared that its eastern border would be the 141st meridian east of Greenwich.

At that time, South Australia had only one neighbor to the east: NSW. But not for long. In 1839, NSW south of the Murray River became the District of Port Phillip, and in 1851 that district became the separate colony of Victoria. The new colony inherited its western border from NSW. However, back in the 19th century, defining a border on a map was one thing; demarcating it on the ground, in the Australian Outback no less, was quite another.

In 1839, surveyor Charles Tyers left a giant arrow made out of limestone rock just east of the mouth of the Glenelg River, at a spot he had calculated as being the 141th meridian. Tyers’ Arrow, on the Southern Ocean, was supposed to be the starting point of an inland surveying expedition.

Owen Stanley, captain of HMS Britomart, made sure that would never happen. Visiting the location some time after Tyers’ expedition, he estimated that the latter’s mark was 2.25 miles east of the 141st meridian. This is where the trouble started, because Stanley’s correction was due to faulty equipment. And Tyers had, in fact, been right.

South Australia’s northern border is the 26th parallel south, which is also the starting point of its eastern border, at the 141st meridian east – but only until the Murray River. Image: Wikimedia Commons & Ruland Kolen

By the mid-1840s, land disputes between sheep farmers in the area between the Murray and the sea necessitated a demarcation of the border between South Australia and the District of Port Phillip. In 1847, surveyor Henry Wade laid down 123 miles of border in a straight south-north line – starting from the point established by Stanley instead of Tyers.

Due to harsh conditions, difficult terrain and broken equipment, Wade had to give up surveying about 155 miles south of the Murray River. Nevertheless, both South Australia and NSW soon accepted his line as the boundary between both territories.

In 1849, Wade’s co-surveyor Edward White completed demarcating the boundary north to the Murray – but in conditions even harsher than on the previous expedition. After just two weeks in the waterless Big Desert, his men had mutinied and two of this three horses had died. When the last one lay down, White drank half a pint of its blood, “which was thick, black and unhealthy-looking and had the same bad smell as his breath,” he later wrote in his diary. Whether or not thanks to that drink, he managed to stagger on for two more miles – reaching the Murray and completing the survey.

By that time, it was already clear that the Wade-White line wasn’t the true meridian. However, both sides having accepted the line for what it was, the new state of Victoria upon its establishment in 1851 inherited the mistake in its favor.

In 1868, it was time to demarcate the border north of the Murray. By then, better instruments were available. So, for the border between South Australia and NSW, it was agreed to revert to the 141st meridian, as per the original definition.

As a result, South Australia’s eastern border follows the Wade-White line south of the Murray, and the 141st meridian to the river’s north. Hence the zigzag at the tripoint with NSW and Victoria, which is called MacCabe Corner.

MacCabe Corner is one of five named state border junctions in Australia. Surveyor Generals Corner is at the tripoint of Western Australia (WA), South Australia (SA) and the Northern Territory (NT).Poeppel Corner is at the tripoint of NT, SA and Queensland (QLD).Haddon Corner is where the SA-QLD border takes a 90° turn south.Cameron Corner is at meeting point of SA, QLD and New South Wales (NSW).MacCabe Corner is at the tripoint of SA, NSW and Victoria (VIC). Image: Yarl, Papayoung & Summerdrought – CC BY-SA 3.0

For South Australia, that zigzag was a stark reminder of what it had lost: a strip of land between the Murray and the sea, 2.25 miles wide and 280 miles long – in all, more than 500 square miles.

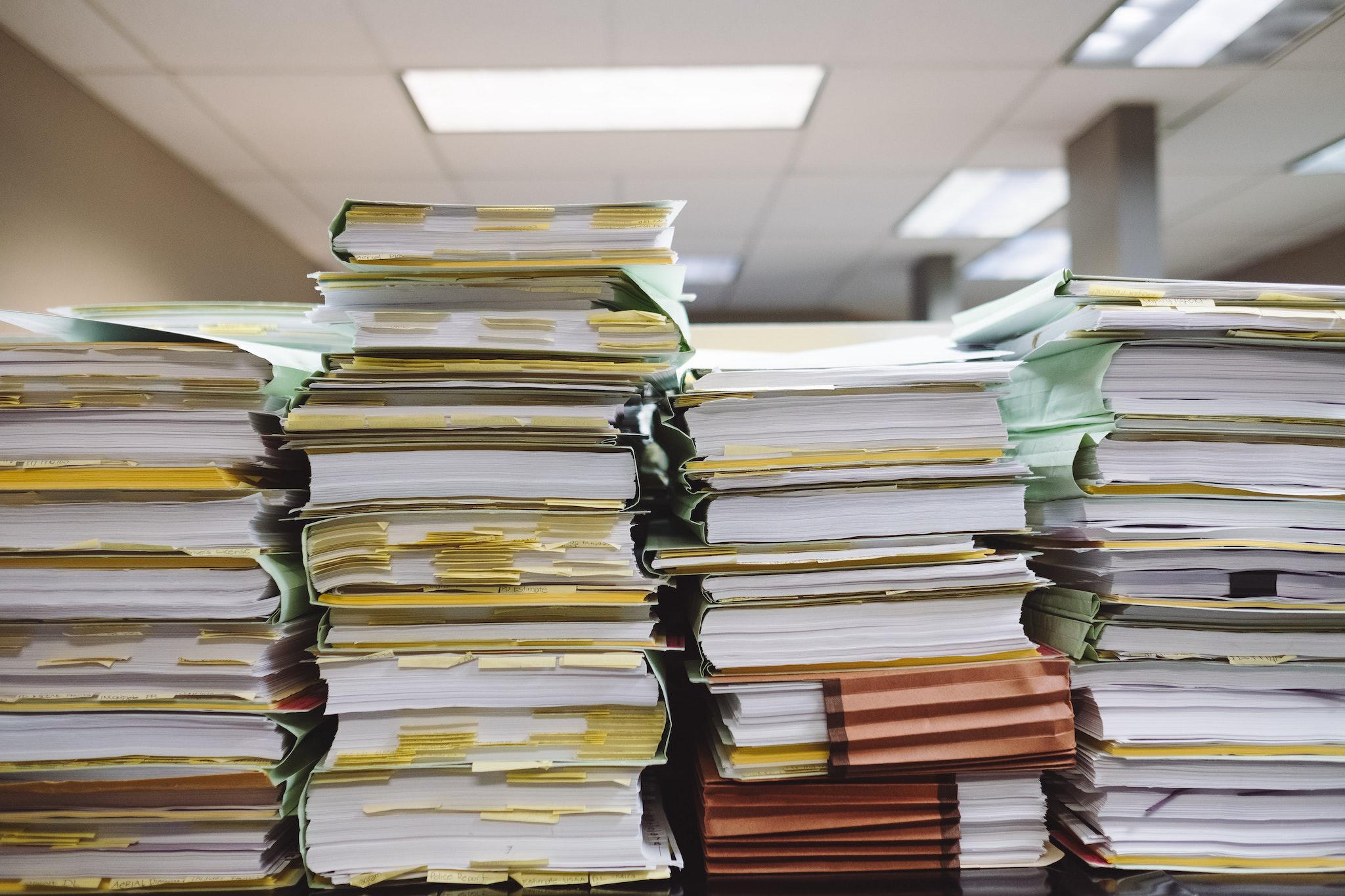

For decades, South Australia disputed Victoria’s ownership of the strip, and tried to reclaim it (or at least get compensated for it). But that was like trying to close the barn door long after the horse had bolted: by 1849, the District of Port Phillip had already sold or leased out 47 percent of the disputed land.

Due to the dispute, the contested strip of land continued to be a bit of a grey zone, legally. In a 1901 referendum, one local cast his vote as a Victorian one day, and as a South Australian the next.

The grey zone was finally erased in 1914, when the Privy Council in London pronounced in favor of Victoria. The court acknowledged that a surveying mistake had been made; but the erroneous border had been accepted by both sides, and that was that.

End of story? Well, not quite. Not if it’s up to the good people of Lindsay Point, an almond-growing community just south of the tripoint, entirely within Victoria – but mainly west of the 141st meridian.

The nearest Victorian cities are more than 100 miles to the east. Most farmers and other locals are oriented towards the Riverland region in South Australia, where they go to school and do all of their business. Conversely, many properties in and around Lindsay Point are owned by South Australians. Even the power comes in from South Australia.

Close-up of the zigzag border near MacCabe Corner, the tripoint where South Australia, New South Wales and Victoria meet, on the Murray River.Image: Google Earth & Ruland Kolen

That level of cross-border economic integration came under pressure in recent months, when Australia’s states started imposing restrictions on interstate travel, due to COVID-19. Specifically, a border lockdown preventing Victorians from entering South Australia has cut off Lindsay Point from its natural hinterland.

With that state border irrelevant in the best of times, and bloody inconvenient in the worst of times, many locals are dusting off the old territorial dispute. Increasingly, they are convinced that the Privy Council’s verdict should not be final, and that it should be settled in favor of the side that lost the first time around.

If it ever does, the result will surely count as the longest, narrowest strip of territory ever to change hands.

More on the low rumblings of secessionism in Lindsay Point in this ABC News story.

Strange Maps #1040

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].