World’s largest solar project will send Australian energy to Singapore

- Australia is the world’s largest coal exporter — but it’s aiming to become a solar-power superpower.

- AAPowerLink, recently greenlit by the Australian government, is a step in that direction.

- The project’s scale and ambition are huge, but so are the challenges, both on land and at sea.

In August, Australia’s environment minister Tanya Plibersek approved the construction of the Australia-Asia Power Link. The $30-billion project, AAPowerLink for short, has the scale and ambition to redraw the world’s sustainable energy map.

Three stand-out superlatives

Several superlatives stand out about the project:

- AAPowerLink will build the world’s largest solar farm on the remote inland of Australia’s Northern Territory.

- It will include the world’s largest battery, near the territorial capital of Darwin.

- And it will feature the world’s longest submarine power cable, connecting farm and battery to Singapore, thousands of miles to the northwest.

All that adds up to the largest solar energy project in the world, so far. When it’s up and running, sometime in the 2030s, AAPowerLink is expected to generate an output of 6.4 gigawatts (GW), about 4GW of which are destined for Darwin and its surroundings, with 2GW to be transported by cable to the distant city-state at the southern tip of the Malay peninsula.

Singapore currently gets 95% of its electricity from natural gas. It’s estimated that AAPowerLink will provide 15% of its energy. That would reduce Singapore’s emissions by 6 million tons of CO2 per year.

At a later stage, the project could also provide power to Indonesia, the country whose waters the power cable traverses. No wonder Plibersek hailed AAPowerLink as a “generation-defining piece of infrastructure” that “heralds Australia as the world leader in green energy.”

A dirty source of energy

But all that jubilation may be a bit premature. For one, SunCable — the company backed by the charismatic tech billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes that is developing AAPowerLink — is still waiting on a Final Investment Decision, slated for 2027, before breaking ground.

Also, around 99% of the solar panels deployed in Australia today are imported, mostly from China. That is a strategic vulnerability. To be fair, the country is trying to remedy this via the so-called Solar SunShot project, which aims to boost domestic production of photovoltaic panels.

Crucially, though, while Australia certainly gets enough sun to be a potential solar power superpower, for the foreseeable future it remains the world’s leading exporter of one of the dirtiest sources of energy: coal. In 2023, Australia accounted for 33.9% of all coal exports worldwide, well ahead of Indonesia, in second place with just 18.2%. On its own, Australia last year exported about 497 million metric tons of coal to other countries.

A giant leap forward

Imagine a cube with sides a mile (1.6 km) wide: That’s about the size of Australia’s 2023 coal export. Burning it would generate about 3.5 billion tons of CO2 emissions. Australia needs to take a massive step to get from that to net zero by 2050, which is its official target. AAPowerLink could be that giant leap forward.

But the project is not just ambitious — it’s also daunting. Take the scale of the proposed solar farm: 30,000 acres (12,000 hectares), which is 46.5 square miles (120 km2), or twice the size of Manhattan. “It will be the largest solar precinct in the world,” promises Plibersek, with a solar capacity between 17 and 20GW, producing around 6GW.

(For context: 1GW could power 10 million incandescent bulbs, 100 million LED lights, or roughly 2,627 Tesla Model 3s. Fans of Back to the Future will remember that it took 1.21GW to power the time-traveling DeLorean’s flux capacitor.)

Roughly the size of Germany

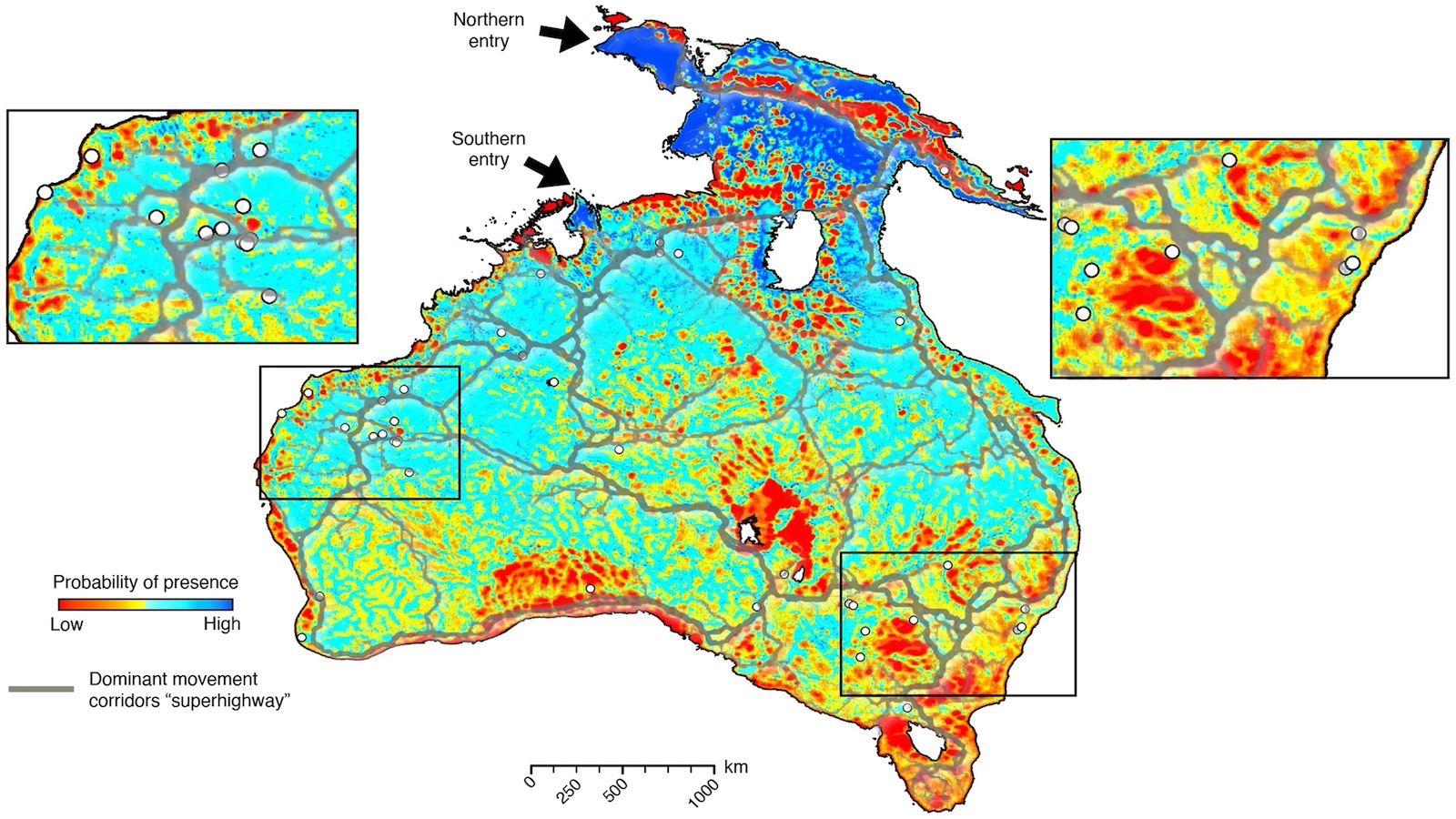

Then there’s the solar farm’s location. It’s set to be built at Powell Creek in the sun-blasted interior of “the T,” as the Northern Territory is often called with typical Australian brevity. In terms of sunshine hours, there’s hardly a better location.

However, its remoteness will come with some operational obstacles. The farm will be in the Barkly Region, one of the Territory’s 17 local government areas. At 124,600 square miles (322,713 km2), it’s roughly the size of Germany. Yet it has a population of less than 7,500.

Additionally, government approval of the project is conditional on the continued protection and survival of the greater bilby, a locally occurring rabbit-like mammal threatened with extinction. Plus, the project still needs the approval of various indigenous groups, who own about half the land in the Territory.

That will include at least part of the 500-mile (800-km) stretch of high-voltage direct current (HVDC) overhead line that will transmit the power generated at Powell Creek to a converter site at Murrumujuk, just northeast of Darwin.

Powering one million households

A giant battery at that location will be able to store between 36 and 42 gigawatt hours (GWh) of energy, providing enough load-balancing capacity to ensure a stable, continuous dispatch of energy for the HVDC submarine cable that will plunge in the ocean at Murrumujuk Beach.

(A GWh, by the way, is the output of 1GW for 1 hour. That’s enough to power up to 1 million households for that same amount of time.)

The subsea cable would link Darwin with Singapore via the sea passages of the Indonesian archipelago: from Darwin across the Timor Sea, between the islands of Bali and Lombok, then north of Java and east of Sumatra, finally arriving at another converter site in Singapore. It would be about 2,670 miles (4,300 km) long, making it the world’s longest submarine power cable — by far.

The current record is held by the Viking Cable, which went online in December 2023. It connects Lincolnshire in England with the west coast of Denmark across 472 miles (760 km) of the North Sea. Although it’s bidirectional in theory, until now it has served primarily to send cheaper Danish wind-generated power to the UK. Currently transmitting 0.8GW of power, it could be upgraded to allow 1.4GW.

Frequent earthquakes and the occasional volcano

The AAPowerLink cable will have a capacity of 2GW, which will allow it to deliver up to 15% of Singapore’s electricity needs. But the project will do much more than that.

It will also power Darwin and its surroundings, which will consume around 4GW, as well as generate around $13.4 billion in economic value for the Northern Territory during construction and the first 35 years of operation of the project. Last but not least, it’s estimated to support 6,800 jobs for each year of construction (both directly and indirectly), with a peak workforce of 14,300.

And who knows, if the project is successful enough to be expanded, the cable could also be branched off to send Australian solar power to Indonesia, or extended to send it elsewhere.

But even in an optimal scenario, Australian solar power will only start flowing into Singapore at some point in the next decade.

And that’s if the project weathers not just the known operational obstacles but also as-yet-unknown issues. One of those could lurk beneath that long stretch of water separating Darwin from Singapore. This is one of the most seismically active regions of the world, which means frequent earthquakes and the occasional volcanic eruption.

That could be bad news for a power cable running across this particular stretch of seabed. Could a volcano turn off the lights in late-21st-century Singapore? As Australia may find out in the years leading up to the next decade: With world leadership in green energy comes a world-class safety and security headache.

Strange Maps #1256

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.