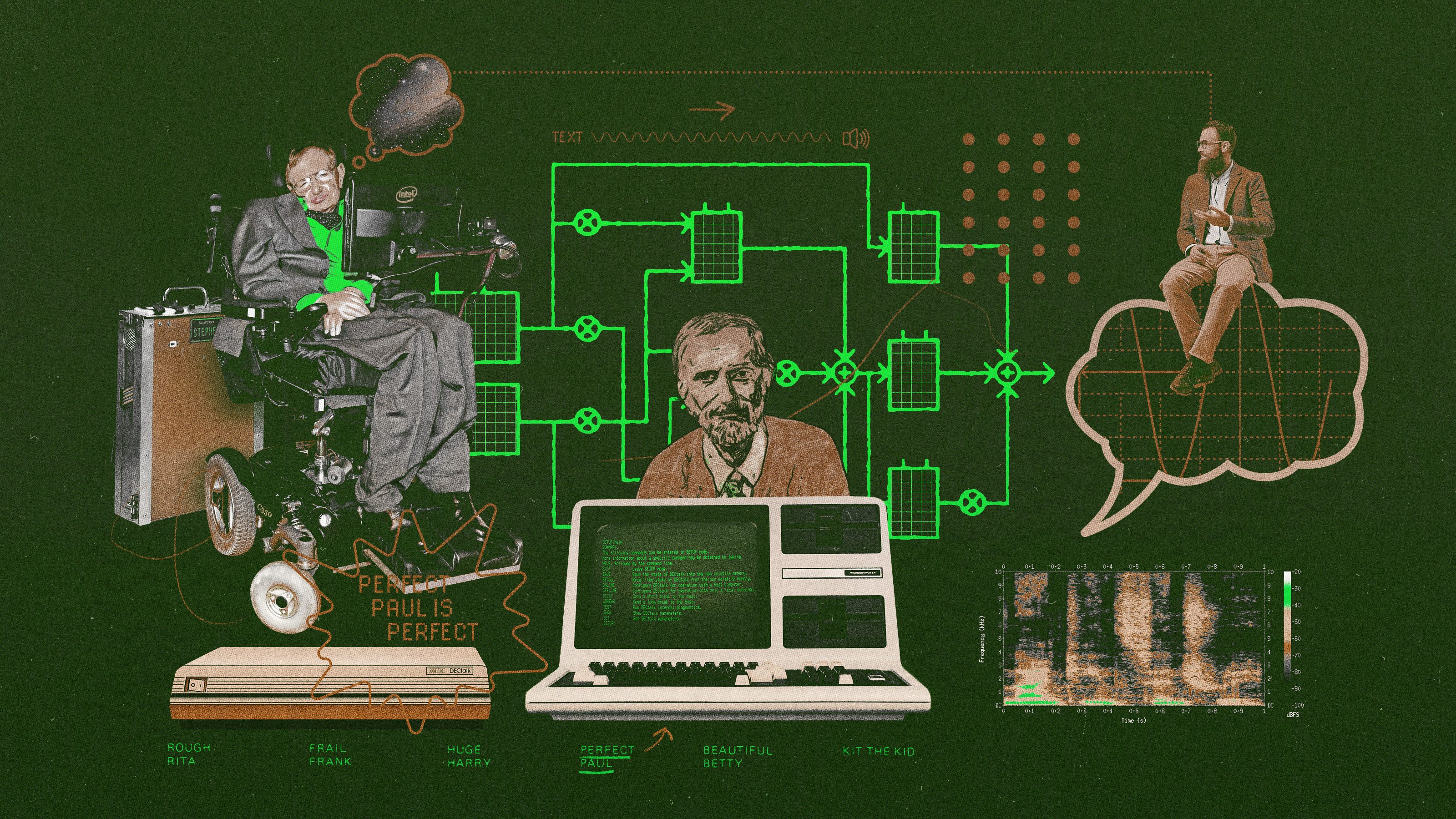

616 – All Quiet on the Illinois Front

It’s the morning of Wednesday, 13 September 1939. In an America supremely at peace, newspapers hit front lawns with headlines screaming of war. The horrific conflict splashed across the front pages of thousands of dailies is happening an ocean away, in Europe.

Two weeks earlier, Nazi Germany had invaded Poland, thus ending all pretense that Hitler’s goal was ‘peace in our time’ [1]. Poland’s main allies, Britain and France, have promptly declared war on Germany. Although the Nazis are focused for now on winning the Polish campaign, it’s clear that this is the beginning of a ‘Second World War’ – a term first used widely in these terrifying days [2].

The front page of the Panama City News Herald, published in Florida, is representative of most other US newspapers during these weeks. Very little local news on the page, which is dominated by articles on the war – both from an American and a European perspective.

One headline wired in from London by the Associated Press reads: British-French Resolve To Fight Until Naziism (sic) Gone, Says Chamberlain. The caption for the page’s main photo says: At German general staff headquarters “somewhere in Poland”, Fuehrer Adolf Hitler, “first soldier of the Reich” looks over map of battle area. His ace military leader, Gen. Walther von Brauchitsch, stands at his shoulder. Picture was radioed to New York from the German capital.

A short message datelined London reads: Duke of Windsor is Ready for Service. Below, an article datelined Boston states, in similar wording: Negroes Ready For Military Service. From Washington DC, the news is: [General] Pershing Urges Bigger Defense Power for U.S., and Neutrality Act Change Sought by President [Roosevelt].

Somewhat prematurely, an article at the bottom of the page predicts the final outcome of the conflict: Poor Gasoline Said to Cause Reich Defeat, while from the North Atlantic come terrible tales of the incipient sea war: Athenia Survivors Tell Horrors of Days in Fear of U-Boats In Atlantic.

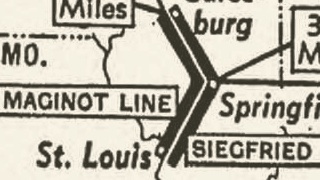

But the most remarkable item on the page – at least from the perspective of this blog – is a small graphic at the top of the page. Titled If Illinois Were Western Front, it is a map of the US Midwest, and it ‘brings the war home’ for the American readership. By grafting the theatre of hostilities in Europe onto the geography of the American heartland, the aim is to make the conflict that is raging on another continent relatable to Joe Q. Public.

The caption reads:

All this talk about history-making battles waged, armies on the march and territory taken sounds big in the day’s war news, but how small it is in American terms may be seen from the map above. Shifted to the American scene, European armies might fight their battles on the Maginot-Siegfried [3] lines in the center of Illinois. This would put London about where Minneapolis is, Paris at Des Moines, Berlin at Toledo, Warsaw at Washington.

Curiously, it seems the way to translate the enormity of the European war to the American public is to scale it down to its ‘true proportions’: folks might have started calling it a World War, but in reality, it could be contained between Minneapolis and Washington…

Many thanks to Dan Anderson for sending in a scan of this map, taken from the Marinette Eagle (published in Marinette, Wisconsin), of 18 September 1939. He notes: “They should have put Paris further west – maybe in Colorado, so that Moscow could be represented”. A slightly sharper image can be found here at the Newspaper Archive, on the aforementioned front page of the Panama City News Herald [4].

________

[1] The actual phrase used by Neville Chamberlain on 30 September 1938 hailing the Munich Agreement was “peace for our time”. Perhaps the misquote stems from the fact that the then British PM was paraphrasing one of his predecessors, in similar circumstances. Following the Congress of Berlin in 1878, Benjamin Disraeli said: “I have returned from Germany with peace in our time”. Chamberlain’s statement is remembered as the epitome of appeasement, the policy born of the misguided hope that agreeing to Hitler’s territorial demands would avoid war. Less than a year after the German occupation of the Sudetenland (as agreed by France and the UK at Munich), Nazi Germany had occupied Bohemia and Moravia, and invaded Poland.↩

[2] The coming conflict had been dubbed the ‘Second World War’ as early as 1920, but mainly in speculative fiction, and hardly ever in the mainstream press. ↩

[3] The Maginot Line is the name for the French fortifications constructed in the 1930s along the German border. The so-called Siegfried Line was the mirror version on the German side of the border. The Germans called it the Westwall. The Siegfried Line was the name for a similar defensive wall built during the First World War; the name was retained by the Allies for the 1930s construction.↩

[4] The logo in the lower right hand corner, spelling NEA, reveals the common source of both: Newspaper Enterprise Association, a syndication service specialising in both images (comics and pictures) and features, supplying content to over 700 newspapers in the 1930s.↩