584 – United Swing States of America: Presidential Election Battle Map

At the stroke of midnight on November 6th, the 21 registered voters of Dixville Notch, gathering in the wood-panelled Ballot Room of the Balsams Grand Resort Hotel, will have just one minute to cast their vote. Speed is of the essence, if the tiny New Hampshire town is to uphold its reputation (est. 1960) as the first place to declare its results in the US presidential elections [1].

Later that day, well over 200 million other American voters [2] will face the same choice as the good folks of the Notch: returning Barack Obama to the White House for a second and final four-year term, or electing Mitt Romney as the 45th President of the United States [3].

The winner of that contest will not be determined by whoever wins a simple majority (i.e. 50% of all votes cast, plus at least one). Like many electoral processes across the world, the system to elect the next president of the United States is riddled with idiosyncrasies and peculiarities – the quadrennial quorum in Dixville Notch being just one example.

Even though most US Presidents have indeed gained office by winning the popular vote, but this is not always the case [4]. What is needed, is winning the electoral vote. For the US presidential election is an indirect one: depending on the outcome in each of the 50 states, an Electoral College convenes in Washington DC to elect the President.

The total of 538 electors [5] is distributed across the states in proportion to their population size, and is regularly adjusted to reflect increases or decreases. In 2008 Louisiana had 9 electors and South Carolina had 8; reflecting a relative population decrease, resp. increase, those numbers are now reversed.

Maine and Nebraska are the only states to assign their electors proportionally; the other 48 states (and DC) operate on the ABBA principle [6]: however slight the majority [7] of either candidate in any of those states, he would win all its electoral votes. This rather convoluted system underlines the fact that the US Presidential elections are the sum of 50, state-level contests. It also brings into focus that some states are more important than others.

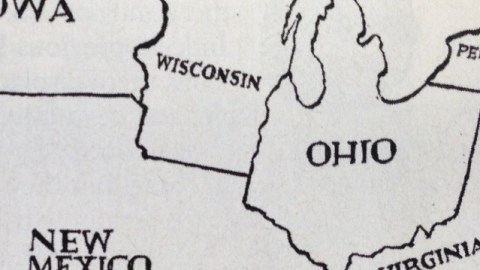

Obviously, in this system the more populous states carry much more weight than the emptier ones. Consider the map of the United States, and focus on the 17 states west of the straight-ish line of state borders from North Dakota-Minnesota in the north to Texas-Louisiana in the south. Just two states – Texas and California – outweigh the electoral votes of the 15 others [8].

So presidential candidates concentrate their efforts on the states where they can hope to gain the greatest advantage. This excludes the fairly large number of states that are solidly ‘blue’ (i.e. Democratic) or ‘red’ (Republican). Texas, for example, is reliably Republican, while California can be expected to fall in the Democratic column.

As shown by this map, the next presidential election will not be decided by 50 states, but by just 11 – the so-called ‘swing states’, that could still go either way. Voters outside these United Swing States of America can, as the legend on this map suggests, just sit quietly and have a beer. So which are these battleground states?

Tacked to the wall of both parties’ war rooms is a slogan to help focus their efforts on these states: It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing. The relatively small number of votes that can win or lose an election here is more important than the millions of votes already tallied up as won or lost in solid red or blue states.

Inhabitants of the swing states can expect a barrage of tv ads from both camps, and frequent visits from either candidate. According to a recent poll, Romney and Obama are neck and neck in these states [9], which together hold 146 votes in the Electoral College – 270 are needed to win. In 2008, Obama won these states with a comfortable margin: 53% to 46%. Obama has a slight lead in Colorado, Ohio, Iowa and Wisconsin, and a better one in Pennsylvania. Romney is ahead in Virginia, Florida and North Carolina. It’s a tie in Nevada and New Hampshire.

Hm, New Hampshire… Who knows, those dozen-and-a-half votes up in Dixville Notch may turn out to be not just the first, but also the most important ones of the whole election…

Many thanks to Roger Huisman for sending in this map, published in The Oregonian on 1 October. Click here for that newspaper’s online version.

_______________

[1] Dixville Notch is the most famous example of the New Hampshire rule that allows smaller precincts to open at midnight and count the votes as soon as all registered voters have cast their ballots. But it isn’t the only one, nor the oldest one. Hart’s Location, 80 miles to the south, started a ‘midnight vote’ for the 1948 presidential elections, but discontinued the tradition in 1964, only to take it up again in 1996. A few other small New Hampshire towns have followed suit.

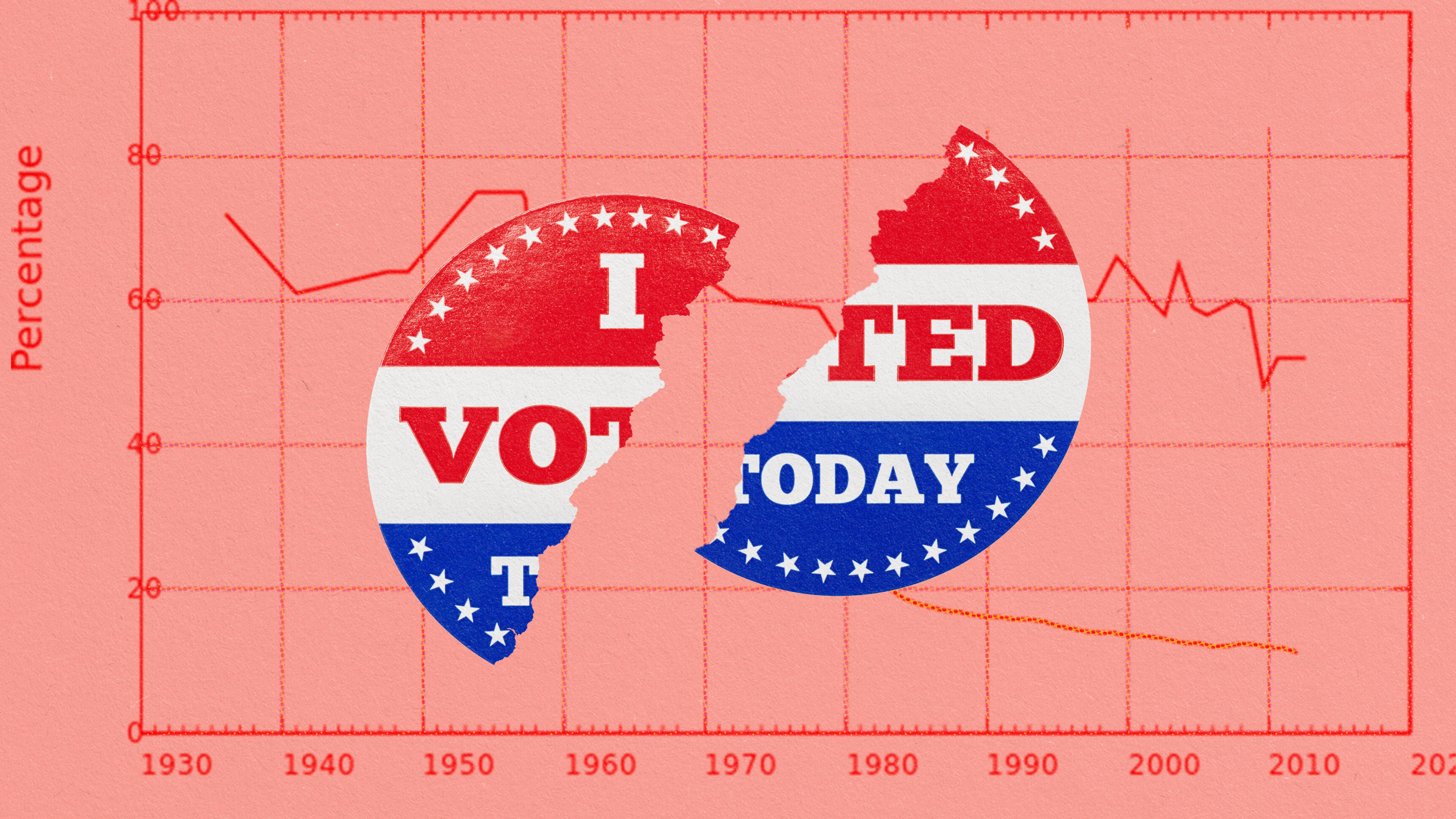

[2] US citizens aren’t automatically voters. In order to exercise their democratic rights, they need to register. Of the 230 million Americans of voting age (i.e. at least 18 years old) during the previous presidential elections in 2008, just over 213 million were registered voters. Of those, 132 eventually turned out to vote, i.e. 62% of all registered voters, and 57% of all potential voters. See this page at the United States Election Project for a more detailed look at the numbers.

[3] Voters could of course pick someone else, if they really wanted. ‘Third parties’ and unaffiliated candidates also vie for the electorate’s favour. Some of the ‘other’ presidential (and vice-presidential) hopefuls that are likely to appear on ballots in most states:

[4] Abraham Lincoln was elected in 1860 with just under 40% of the popular vote, the worst score ever but for John Quincy Adams (30,9% in 1824); more recent popular ‘losers’ who became electoral ‘winners’ were Woodrow Wilson (41.8% in 1912 and 49.2% 1916), Harry Truman (49.5% in 1948), John F. Kennedy (49.7% in 1960), Richard Nixon (43.4% in 1968), Bill Clinton (43% in 1992 and 49.2% in 1996) and George W. Bush (47.8% in 2000).

[5] This equals the number Members of Congress (435 Representatives, 100 Senators), plus three delegates from Washington DC.

[7] Or, in the case of more than two candidates, a plurality (i.e. the most votes, but not an absolute majority).

[8] California’s 55 electoral votes and Texas’s 38 add up to 93. The electoral votes of all the other 15 western states add up to 90.

[9] On Oct. 13, a Rasmussen Swing State Poll put Romney at 49%, Obama at 48%, with 3% undecided. This puts the difference between both candidates within the margin of error of 3%. Also, the Rasmussen list of 11 swing states excludes New Mexico and includes Michigan.