568 – Last Chance to See: a Euro-graphy of France

George Soros last Sunday blamed Angela Merkel for the euro crisis – and gave her three months to fix it. Speaking at the 7th Festival of Economics in Trento (Italy), the renowned hedge-fund magnate pinpointed the moment when Germany, traditionally the engine of European integration, reversed gears:

“The process [of European integration] culminated with the Maastricht Treaty and the introduction of the euro. It was followed by a period of stagnation which, after the crash of 2008, turned into a process of disintegration. The first step was taken by Germany when, after the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, Angela Merkel declared that the virtual guarantee extended to other financial institutions should come from each country acting separately, not by Europe acting jointly. It took financial markets more than a year to realize the implication of that declaration, showing that they are not perfect.”

Maastricht’s creation of a monetary union without a political one is now seen as a fundamental flaw of the euro project. A consequent, and almost equally common view is that Mediterranean countries then took advantage of the stability provided by the euro to engage in gross fiscal irresponsibility. But Soros decried the euro’s political deficit as a ‘Third-World’ burden on countries on the eurozone’s economic periphery: heavily indebted, in a currency they can’t control (i.e. devaluate).

The ‘centre’ (read: Germany) deserves quite a bit of blame, Soros said, for “designing a flawed system, enacting flawed treaties, pursuing flawed policies and always doing too little too late”, continuing that “[i]n the 1980’s Latin America suffered a lost decade; a similar fate now awaits Europe.”

Indeed, one of the remarkable constants in Europe’s reaction to the unfolding crisis, at crisis summit after crisis summit, is to do just enough to avert disaster, but nowhere near enough to fix the fundamental flaws of the system. Mainly, snorts Soros, because they don’t understand the system’s flaws. Or is there a hidden agenda? If Germany does just enough to save the euro, but not correct its inherent imbalance, then the European Union will become, in the words of George Soros, “a German empire with the periphery as the hinterland.”

Between total collapse and a German-dominated collection of economically subservient states, Soros sees a third option. He foresees that European autorities (i.e. the German government and the Bundesbank) have a “three months’ window” to correct mistakes and reverse the trend towards disintegration.

But this will require a much larger commitment from the European summit at the end of June than the ‘temporary relief’ offered by previous ones. After the window closes, the gap between market demands and the eurozone’s options will become unbridgeable. The subsequent breakup of the euro could chain-react and cause “a collapse of the Schengen Treaty, the common market, and the European Union itself.”

All of which is both terrible and important, but what – I hear you think [1] – does this have to do with maps?

Although reports of its demise are at least three months premature, the death of the euro would also kill off an interesting experiment in monetary geography, which has been made possible by a peculiar geo-locator built into every euro coin: its face bears the imprint of the eurozone member state for which it was minted.

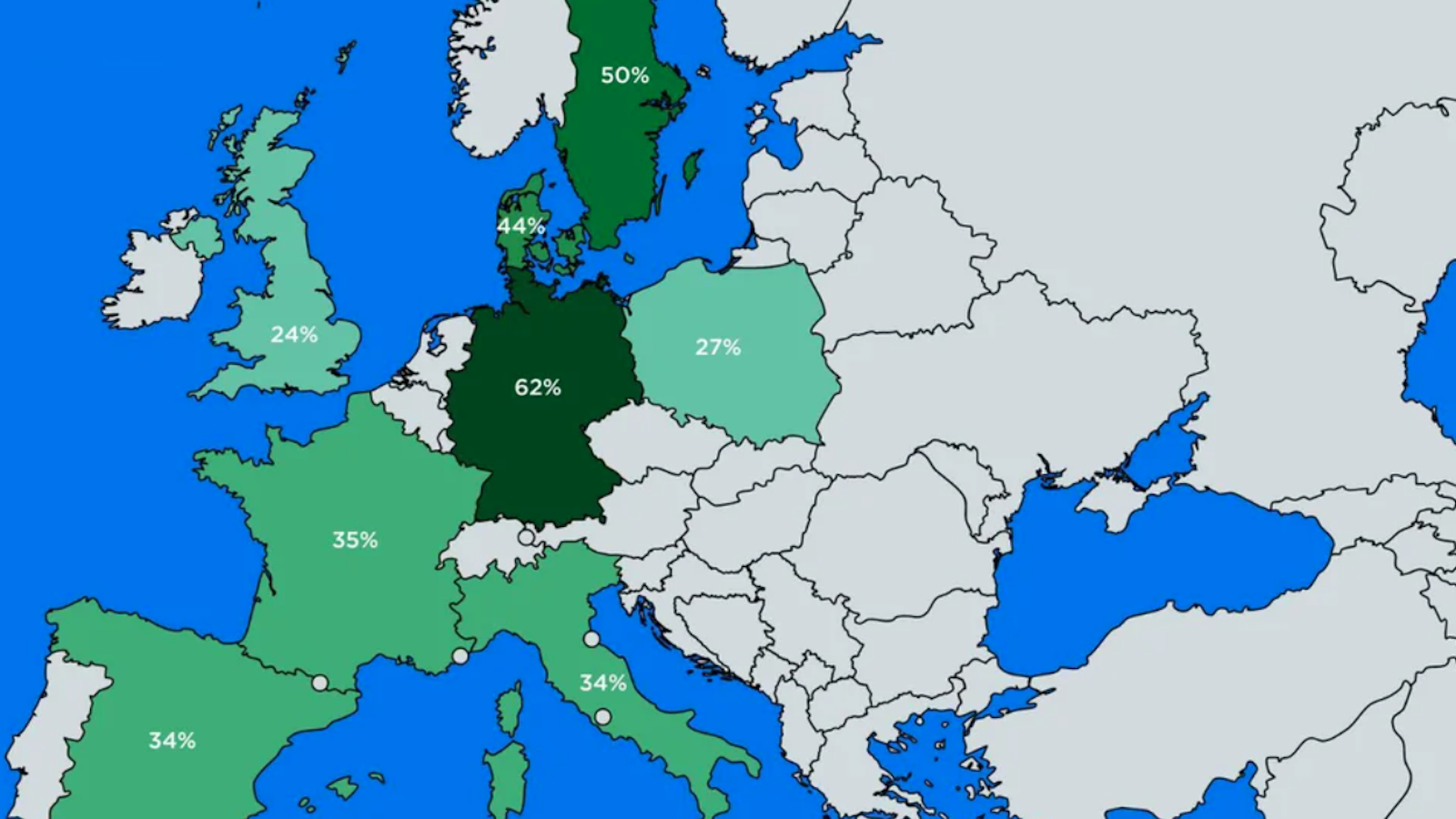

Progression of foreign euro coin penetration into France (March-June-September 2002)

Progression of foreign euro coin penetration into France (January 2003 – January 2007 – December 2011)

This allows for all kinds of statistical fun, including the maps published in November 2002 by INED, France’s National Institute for Demographic Studies. The euro coin diffusion study [2], conducted just a few months after their introduction on New Year’s Day 2002, showed the rapid infiltration of the coinage of France’s neighbours into the Hexagon.

These were the early, heady days of the eurozone. In the intervening decade, the monetary attitudes has completely turned: instead of uniting the continent, the euro may well turn out to be the bomb in the European beehive. So when INED took another snapshot of euro coin diffusion in France earlier this year, it could be that their two studies prove to be the bookends on a very short experiment in European monetary union.

In another decade’s time, there might not be any euro coins anymore – at least not in circulation as legal tender. So perhaps this is your last chance to see a proper euro coin diffusion analysis in action. Narrow your eyes and let your imagination do the work: there are the French statisticians, mounting their horses, charging the unsuspecting public, shouting: “It’s a good day to survey!”

Their study relies on surveys conducted over the last ten years, during which respondents were asked to empty their purses and pockets of euro coins. Some conclusions:

Foreign coin share

In 2002, 24% of the surveyed Frenchmen and -women had at least one foreign coin in their purse, by 2005, this had increased to 53% and by the end of 2011 to 89%.

The total share of foreign coins in French purses increased from 5% in March 2002 to 34% in December 2011. This is far from a ‘statistically perfect’ mix. France minted only 20% of all euro coins, implying a statistical ideal of 80% in non-French euro coins in French purses. “[I]t is clear that the mixing process has been slower than predicted by physicists and mathematicians”, the researchers find.

Geographic differentiation

The slowness of the mixing process has a definite geographic angle: in northeastern France, close to Germany, over half of coins are foreign, while in Brittany, in France’s far west, three quarters are still French. In 2003, the coins were 15% and 5% foreign in the respective regions.

Relative slowness may be attributable to two different types of foreign coin diffusion: in border regions, where coin infiltration is intense but ineffective, as coins move back across the border with equal speed; and as a result of long-distance travel, which is more effective if it weren’t so relatively limited in scope.

Coin mobility

Coin mobility is different per denomination. The 1 euro coin is the best mixer, with foreign coins representing 60% of the French total. The foreign 2 euro and 50 cent coins mix almost equally well, representing 56% and 55% of the French total, respectively.

Smaller denominations are less ‘sociable’, with 20 cent at 45%, 10 cent at 34% and 5 cent at 23%. The worst mixers are foreign 1 and 2 cent-coins, both at 12%.

Coin ‘nationality’

The most frequent ‘nationalities’ of foreign coins found in French purses in December 2011 were, in descending order: Spanish, German, Belgian and Italian – all direct neighbours of France [3]. Spain and Germany each represent just over 25% of foreign coins in France, Belgium and Italy each just under 15%.

As the weight of the eurozone countries’ respective demographies and economies takes more effect, the Belgian and Spanish share should continue to decrease, while the German and Italian share keeps increasing.

Penetration of neighbours’ euro coins into France (December 2011)

Cross-border commerce

The degree of penetration of foreign coins into the French hinterland is a good indication of the strength of cross-border commerce.

Many thanks to Jean-Pierre Muyl, who alerted me to the updated study. It’s viewable in its entirety here (in French and English versions).

______________

[1] Yes, there’s an app for that too.

[2] See Strange Maps #359 for an overview of the 2002 study.

[3] Luxembourg also mints its own euros, but since each country does so proportionally, the tiny Grand Duchy’s coins don’t make much of an impact – it comes in at 9th place, with about 2%. Andorra, in between Spain and France, has adopted the euro but does not mint its own. Switzerland, on France’s eastern border, is outside the European Union and the eurozone, holding on to its Swiss franc.