56 – The Vinland Map

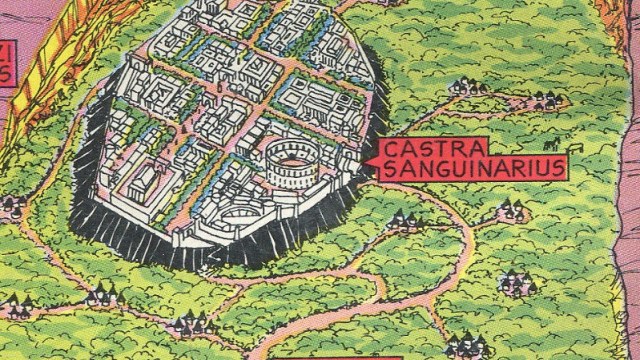

The Vinland Map was discovered in 1957, bound up with a manuscript of undisputed antiquity, the Historia Tartorum. The map supposedly is a 15th century copy of a 13th century world map, showing the known parts of Europe, Asia and Africa, as well as an unknown land across the Atlantic Ocean labelled Vinland. The map also mentions that Vinland was visited in the 11th century.

n

This corresponds well with a tradition in Viking folklore that Norsemen, using Iceland and Greenland as stepping stones, had a more or less regular contact with North America. According to some Icelandic sagas, North America was sighted in about 986 by Bjarni Herjolfsson, who was blown off course on a trip from Iceland to Greenland. His stories lured Leif Eiriksson on an expedition in the year 1000, on which he named (north to south):

n

Helluland (“Flatstone Land” – possibly present-day Baffin Island)

nMarkland (‘Wood Land’ – possibly Labrador) and

nVinland (‘Grapevine Land’ or ‘Pasture Land’ – possibly Newfoundland)

n

Eiriksson established two settlements: Straumfjördr in the north and Hop in the south. Both attempts failed quickly, also due to attacks from the native skraelingar (‘barbarians’), and were never repeated.

n

In 1960, archeological excavations at L’Anse-aux-Meadows on Newfoundland turn up the remains of a Viking camp. For the first time, scientists establish that Vikings actually did cross the Atlantic. Interest in all things Vinland soars. Yale University buys the map in 1965, has it insured for $25 million and publishes it in that same year. That was the starting point for two debates that rage to this day: Where is Vinland? And: Is the map real?

n

n

Some have placed Vinland in New England, after 1960 many were sure it was at L’Anse-aux-Meadows, thinking any location more southernly unlikely. Others postulated that L’Anse was an undocumented colonisation attempt, leaving open the possibility of Vinland having been more to the south, some would say as far south as present-day Rhode Island.

n

The map’s authenticity is maintained by Yale at its second edition in 1995. Which is remarkable, considering the amount of criticism it has had to endure. Such as:

n

While the map has been radiocarbon-dated to between 1423 and 1445, it appears to have been coated with an unknown substance in the 1950s. This could be an undocumented attempt at preservation, or it could be part of a forger’s attempt to draw a new map over an old one. It’s unclear whether this substance is over or under some of the ink on the page…

nThe ink itself has been chemically analysed, and dated to after 1923 due to the presence of anatase – a synthetic pigment in use only since the 1920s. Natural anatase has been demonstrated in various Mediaeval manuscripts, though.

nAs for the content of the map, a number of questions challenge the age of the document. Greenland is presented as an island – a fact not physically proven until the turn of the 20th century and unknown to the Vikings, who mostly thought it a peninsula descending from the north. Several passages in the text are equally anomalous.

nFinally, the best argument against the map’s veracity seems to be that the Vikings were such good seafarers that they didn’t use nautical maps at all…

n