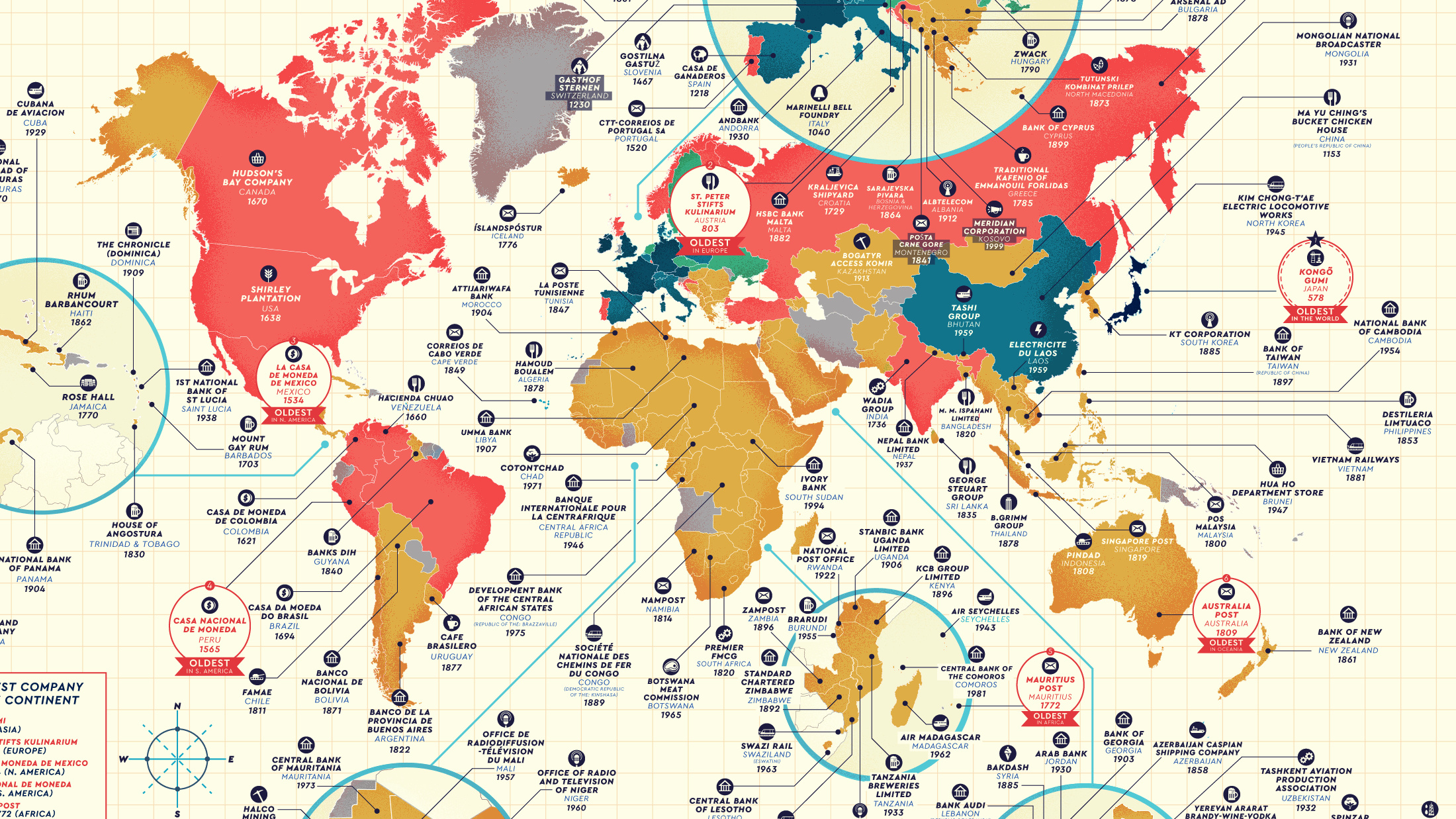

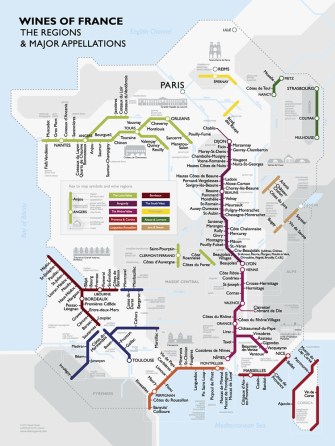

533 – Next Stop Beaujolais: A Metro Map of French Wines

Wine maps are appreciated mainly by the select few who are both cartophiles and oenophiles. Those who are either or neither face a formidable obstacle to cartographic enjoyment, inherent in viticulture: wine regions are a mess to map.

In wine-making, the hyperlocal is paramount. Soil type and microclimate, production and processing methods, taste and reputation – not least the type of grapes involved – all help explain the widely differing oenological appreciations of relatively small, often adjacent plots of land.

This is why traditional wine cartography resembles a map of rampant feudalism, with a confusing jumble of tiny dominions ineffectually jostling for the attention of the map reader.

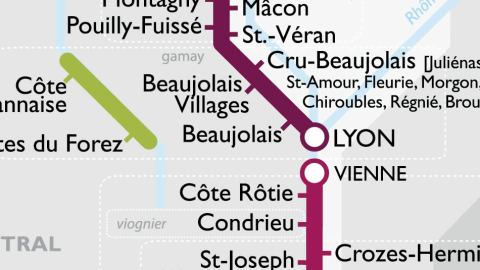

That defect is brilliantly resolved by this map, which borrows its clarity from the metro map. The accepted formula for such maps, pioneered by Harry Beck [1] for the London Underground in 1931, is to reduce the complexity of actual metro line topography to a schematicsimplicity: lines connecting dots with the utilitarian simplicity of an electrical circuit.

The coloured lines on this wine map denote the main wine-producing regions in France, the dots are significant cities or towns in those regions. Names that branch off from the main line via little streaks are the so-called appellations [2].

This schematic approach is illuminating for non-aficionados. In the first place, it clarifies the relation between region and appellation. For example: Médoc, Margaux and St-Emilion are three wines from the same region. So they are all Bordeaux wines, but each with its own appellation.

Secondly, it provides a good indication of the geographic relation between appellations within regions. Chablis and Nuits-St-Georges are northern Burgundy wines, while Beaujolais is a southern one. It also permits some comparison between regions: Beaujolais, although a Burgundy, neighbours Côte Rôtie, a northern Rhône Valley wine.

And lastly, it provides the names of the main grape varieties used in each region (the white ones italicised), like merlot or chardonnay.

In all, this map lists 10 major wine regions in France. Apart from Bordeaux (coloured in a tint of red I’d be foolish not to call bordeaux), these are: the Loire Valley (green), Burgundy (burgundy red), the Rhône Valley (beetrooty red – sorry, Rhône valleyers), Provence & Corsica (proper red), Languedoc-Roussillon (orange), the South West (blue), Champagne (yellow), Alsace & Lorraine (dark green), and Jura & Savoie (brown).

What’s not clear from this map, however, is how the geographic proximity (or distance) of certain wines relates to the similarity (or not) of their taste. But that’s asking too much of a mere map. This is where cartographic curiosity might be complemented by a wine-tasting – where cartophilia and oenophilia meet…

Many thanks to Steve De Long and Hervé Saint-Amand for sending in this map. Mr De Long is in the business of offering Wine Discovery Tools (maps, charts and tasting guides); the Metro Wine Map, designed by Dr David Gissen, is his latest offering.

——–

[1] Mr Beck’s diagram is a popular matrix for presenting just about any type of categorical information. Previous examples discussed on Strange Maps include Bloomsday (#518), the Mississippi (#501), and, deliciously self-referential, a world map of metro systems (#212).

[2] An appellation is a legal definition and protection of the geographical origin for food. Often for wine, most famously for French wine – on the label, look for Appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC) to ensure that your wine is grown in an officially recognised terroir (derived from terre – ‘land’ – this term has come to define the particularity of agricultural regions).