433 – Plotting Vineland: the Skálholt Map

The Vikings set foot in America just over a millennium ago, but credit for the discovery generally goes to Columbus, who only stumbled upon the New World almost 500 years later. One reason might be that the Norse involvement in North America was brief and inconsequential, whereas Columbus’ rediscovery led to the European conquest of the Americas. Another is that the Norse discoverers didn’t leave behind any maps of the lands they called Markland, Helluland and Vinland (*).

But if the Vikings didn’t map their discoveries, they did relate them in sagas. These later did form the basis for maps, the most famous of which is the Vinland Map. Reputedly a 15th-century copy of a 13th-century original, that map, now in the possession of Yale University, is likely to be a clever, relatively recent forgery (see #57 for a more thorough discussion).

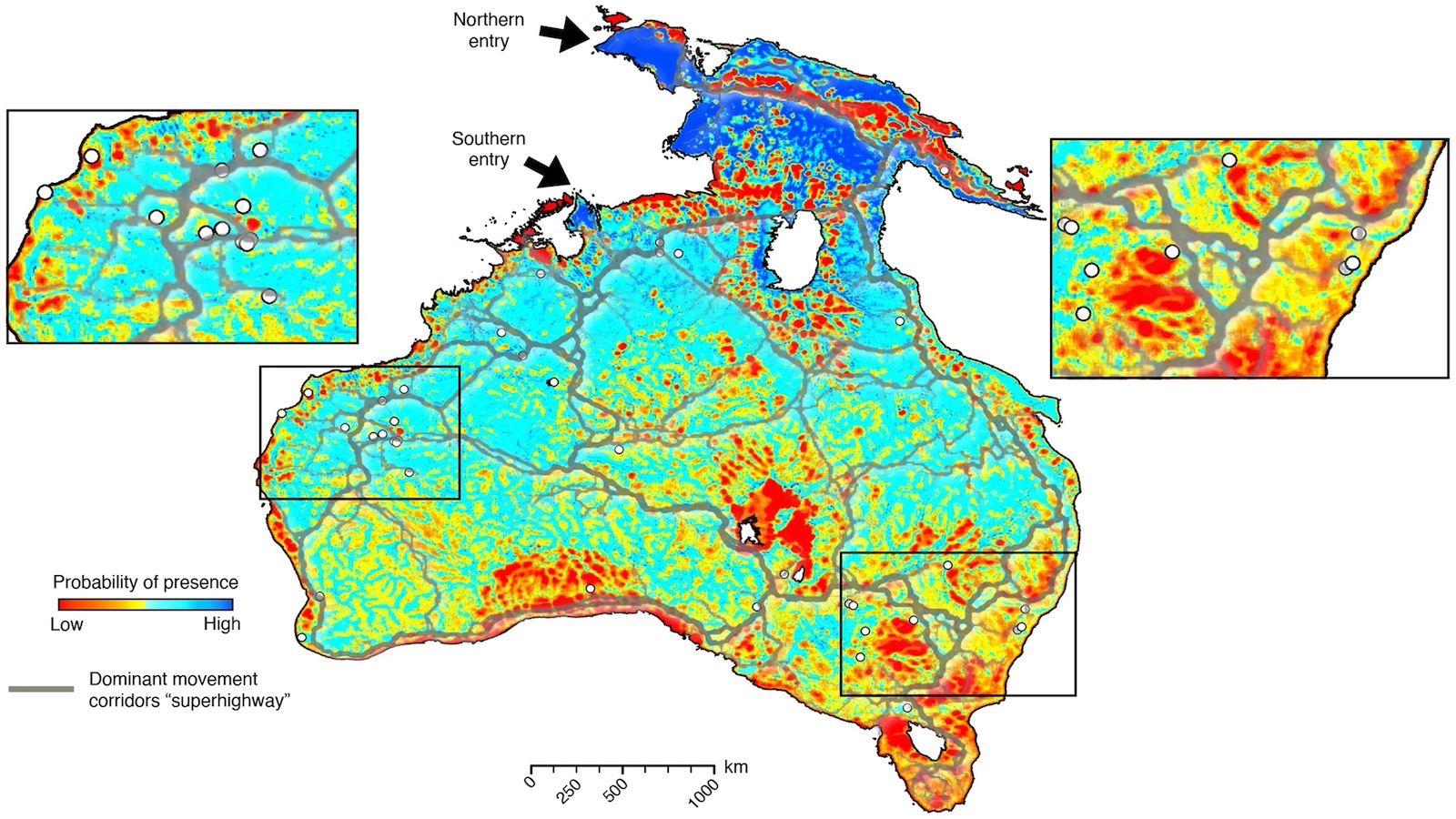

The Skálholt Map, shown here, is less well known, but has the advantage of being authentic. The first version was made in 1570 by Sigurd Stefánsson, a teacher in Skálholt, then an important religious and educational centre on Iceland. Stefánsson attempted to plot the American locations mentioned in the Vinland Saga on a map of the North Atlantic. Stefánsson’s original is lost; this copy dates from 1669, and was included in description of Iceland by Biørn Jonsen of Skarsaa.

The map mixes real, fictional and rumoured geography. In its southeast corner, the map shows Irland and Britannia, and to the north of both the Orcades (Orkney Islands), Hetland (Shetland Islands), Feroe (Faroe Islands), Island (Iceland) and Frisland, a particularly persistent phantom island discussed earlier on this blog (#62).

The northeast part of the map shows the mainland of Norvegia (Norway) and to its north Biarmaland (the semi-mythical Bjarmia, possibly the area of present-day Archangelsk). On the top part of the map are situated the wholly fictional lands of Iotunheimar (Jotunheim, in Norse mythology the home of the giants) and Riseland (another land of titans), with attached to it Gronlandia (Greenland), its flowing coastline resembling the lobed margins of an oak leaf.

In the Mare Glaciale (Ice Sea) in the north is Narve Oe, possibly translatable as the Island of Narfi (the father of Nott, the night). Two place names, both on Greenland, are illegible.

Greenland is of course an island, but was considered by the Vikings to be a huge peninsula of a contiguous northern mainland, that continued to America, where are noted Helleland, Markland and Skraelingeland (after the Viking name for the natives). Marked vertically on the map’s southwestern edge is the name Promontorium Winlandiae (Promontory of Vinland).

In a development that would have pleased Stefánsson, the Skálholt Map has helped determine the actual location of a Norse site in North America. The map indicates that the northern tip of Vinland is on somewhat the same latitude as the southern coast of Ireland (app. 51°N). This encouraged the excavations at L’Anse-aux-Meadows on the northern tip of Newfoundland, which in 1960 yielded the first archaeological evidence of Viking presence in America.

This map was taken from this page at the Kongelige Bibliothek, the Danish Royal Library. The vignette, in Latin, refers to the original map by Siurdus Stephanius (Sigurd Stefánsson). The numbers on the map match the legends (A to H) next to the map, also in Latin. Can anyone provide a translation?

———-

(*) Generally translated as Flatstone Land, Wood Land and Grapevine Land, respectively.

![SKA00020[1]](http://strangemaps.files.wordpress.com/2010/01/ska000201.jpg)