Paris, Capital of French Peasants

Well into the 19th century, much of France languished in a pre-modern limbo, hardly touched by the Enlightenment, Christianity or even the Roman civilisation that had preceded both. Outside the big cities, Ancient Gaul seemed a more vivid and relevant influence than the French Revolution.

France’s shockingly recent ‘pagan’ past (from the word paganus, not coincidentally Latin for ‘rustic’) is resurrected in Graham Robb’s The Discovery of France, a fantastic study brimming with fascinating portraits, meticulously reconstructed scenes and bizarre facts about a country before it was centralised, homogenised and tamed by its rationalist hub, Paris.

Up until the early 20th century, Robb suggests, it still seemed the other way around. It was Paris that was being colonised, by its provinces:

“By the mid-nineteenth century, half the inhabitants of Paris came from the provinces and most of them did not consider themselves Parisian. Migrants spent as little money as possible while away from home. Mentally, they never left their pays (…) In certain Paris streets, the sounds and smells of villages and provincial towns drowned out the sounds and smells of the capital. For many, their street cry was the only French they spoke.”

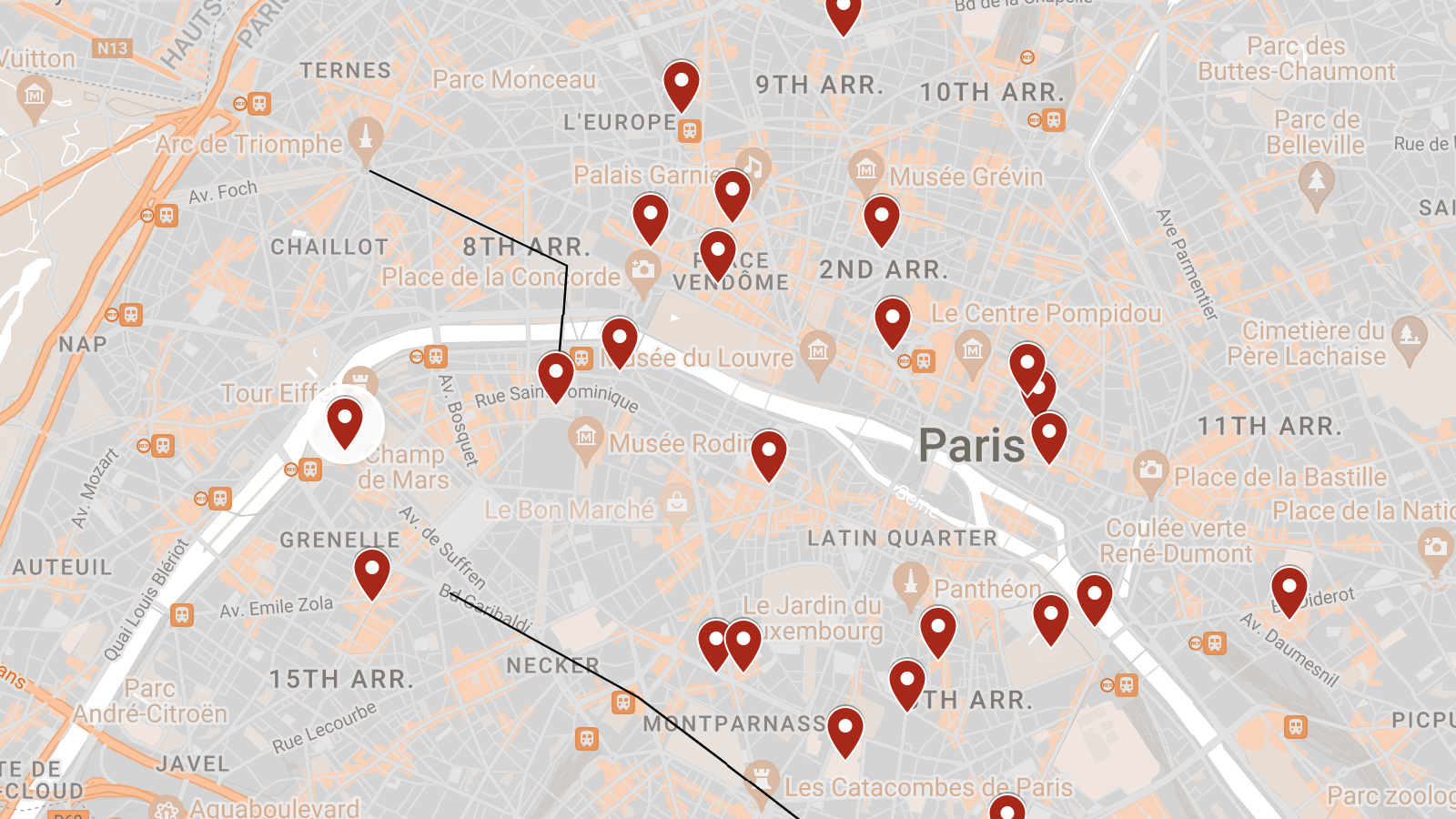

“Tinkers and scrap-metal merchants from a particular valley of the Cantal were concentrated around the Rue de Lappe near the Bastille. Water-carriers and labourers from the neighbouring valley lived in the same quartier, divided from their compatriots by a street instead of by the river Jordanne.”

“All the people involved in the conspiracy on which Alexandre Dumas based The Count of Monte Cristo came from the same part of Nimes and lived in the same quartier in Paris, between the Place du Chatelet and Les Halles (…) Traces of these urban villages are still visible, especially near the big railway stations: the name of a cafe or restaurant, a regional dish, a waiter’s accent or a photograph of a cow in a mountain meadow.”

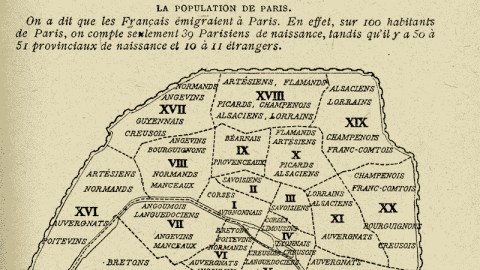

This map illustrates Mr Robb’s point exactly. The accompanying graph shows how, even in 1920 (the publication date of this map), fully half of the population of Paris was born outside the city, as compared to only 39% of native Parisians. The map itself shows how these new Parisians huddle together in regional ghettos, no doubt originated by the ancestors of most of those ‘native’ Parisians.

This Paris of urban villages is a fairly accurate reflection of the geography of France in general: Artesians, Flemings and other northerners congregate in the 18th arrondissement, in the north of the city. Bretons and Normans from out west settle in the westerly 15th and 16th arrondissements, Corsicans in the southerly 14th and Burgundians from the east in the easterly 20th.

The legend explains that les provinciaux “generally establish themselves near the terminal stations of the railways leading to their native province. For example, the Bretons live near the gare Montparnasse, people from Creuse and Gascony near the gare d’Orleans and Flemings close to the gare du Nord, etc.”

Although the map reflects fairly old and by now dried-up currents of migration, one aspect seems entirely modern: the ammunition it must have provided to those nativists who feared the Überfremdung of good old Paris by newcomers caring more for their native valleys than for their new home.

Many thanks to Maciej for providing me with this excellent map.

Strange Maps #360

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].