311 – Transnistria, A Soviet Fly in Geopolitical Amber

Now that Russia has recognised the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the improbable phantom nation of Transnistria (1) might be gearing up for its own fifteen minutes of geopolitical fame. Like the aforementioned breakaway regions of Georgia (itself a former Soviet republic), Transnistria is a bizarre splinter off the old Soviet block, and now a client state of Russia.

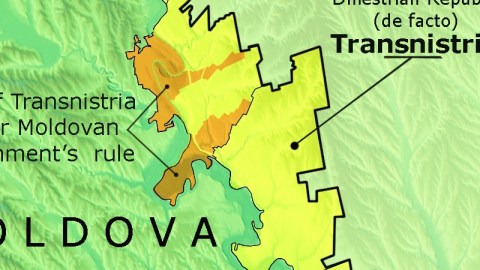

Transnistria occupies the sliver of Moldovan territory hemmed in between the river Dniester (2) in the west and the Ukrainian border in the east. It is about 400 km long, from north to south, and typically no more than 20 km wide, sharing its snake-like look on the map with a few other nations, notably Chile, Norway and the Gambia. Except that Transnistria doesn’t appear on most maps. No other country recognises the independence of this freak accident of world politics, not even Mother Russia – at least not yet (3).

The birth of Transnistria is an indirect result of the death of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union broke up in the early 1990s, Moldova was one of the 15 constituent republics that gained its independence. Moldova, which shares language, culture and history with neighbouring Romania had the distinction of being the only Romance-language Soviet republic. Its ‘western’ orientation hasn’t helped it integrate into Europe, as the Baltic states have done: Moldova remains one of the poorest countries on the continent, notorious for corruption, smuggling and prostitution.

It may be argued that Moldova’s near-failed-stateness is the cause – or the effect – of its conflict with Transnistria. That strip of Moldovan territory was heavily industrialised in Soviet times, and populated with migrants from other parts of the Soviet Union: Russians, Ukrainians and others. That typically ‘Soviet’ mix of nationalities felt no desire, post-USSR, to be integrated into a state dominated by Moldovans, and looked east for protection.

Cossacks and Russian regular troops helped Transnistria fight its brief war of independence from Moldova in 1992. Since then, the rogue republic has remained virtually unchanged, frozen in time like a Soviet fly in geopolitical amber. Lenin statues still adorn the Transnistrian town centres, and the main ideology seems to be nostalgia.

The self-declared republic’s regime is styled as ‘super-presidentialism’ under the leadership of one Oleg Smirnov (4), who managed to obtain 103.6% of the votes in a particular district during the 2001 election. Transnistria still has a large manufacturing base, and profits greatly from non-regulated exports (or ‘smuggling’, if you’re into the whole brevity thing) and other activities that thrive best in the twilight of disputed sovereignty, including arms manufacturing.

Transnistria might yearn for the sunny Soviet past, but those days are not returning. These days, it’s one of Russia’s westernmost outposts, an illegal, southern mirror site to Kaliningrad, which sits uncomfortably on the Baltic coast, completely hemmed in by the EU member states Poland and Lithuania. Transnistria is similarly surrounded by Moldova and the Ukraine, which has in the past exerted pressure on the small statelet as a way of getting back at Russia.

A notable example was the gas crisis of 2006, in which Russia suddenly and dramatically raised the price of its gas exports to Ukraine – a warning to its newly-elected, pro-western president Yushchenko not to stray too far from Moscow’s sphere of influence. Ukraine retaliated by instituting measures to stem Transnistria’s illegal exports, strangling the local economy. This mechanism of war by proxy might make Transnistria a more ‘convenient’ flashpoint in a future conflict between Russia and the Ukraine than the Crimea, the sovereignty of which is directly disputed between both countries.

This map taken from this page at moldova.org – “Moldova’s best international gateway”.

———-

(1) Official full name: Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic. Also known as Transdniestria, Transdniestria and Pridnestrovie (the latter its Russian short name). Some official Moldovan sources insist on not using the region’s self-chosen name, but instead refer to it as the ‘Administrative-territorial unit of the Left Bank of the Dniestr’.The implication is that using the name chosen by a wayward territory for itself opens the door for its official recognition.. This is reminiscent of the insistence of some Arab sources to refer to Israel as the ‘Zionist Entity’.

(2) Hence the breakaway republic’s name, literally ‘across the Dniester’. The river’s name derives from ancient Sarmatian, and can be translated as “the near river”. The Dnieper River, from the same source (linguistically, not hydrographically), means “the far river”. The old Greek name for the Dniester is Tyras, which still survives in the name of the Transnistria’s capital, Tiraspol.

(3) Tellingly, both Abkhazia and South Ossetia have recognised Transnistria’s independence.

(4) Real name.