The ‘Réduit’, Switzerland’s Invasion Survival Plan

One of the most famous quotes about Switzerland –probably annoying the hell out of the natives by now – is the closing line of the film ‘The Third Man’:

“In Italy for 30 years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder, bloodshed – but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, 500 years of democracy and peace. And what did they produce? The cuckoo clock.”

The line was not in Graham Greene’s original script and was inserted by Orson Welles, who himself plays Harry Lime, the character making the remark. Welles did not invent this witticism, stealing it from Mussolini. And Mussolini was wrong on several counts. For one, the Swiss did not invent the cuckoo clock – that honour should go to the artisans of the Black Forest. And Switzerland wasn’t always peaceful, experiencing its share of civil strife. In fact, Swiss mercenaries had such a reputation for efficiency in battle that the Papal Guard to this day still is composed solely of (Roman catholic) Swiss men.

The Swiss have always prided themselves on their military prowess, which allowed them to remain neutral throughout most of Europe’s wars. Of course, the indomitable alpine terrain helped too: the mountains dominating (most of the southern part of) the country make it very difficult for any would-be conqueror to subdue the locals, who know every nook and cranny of it.

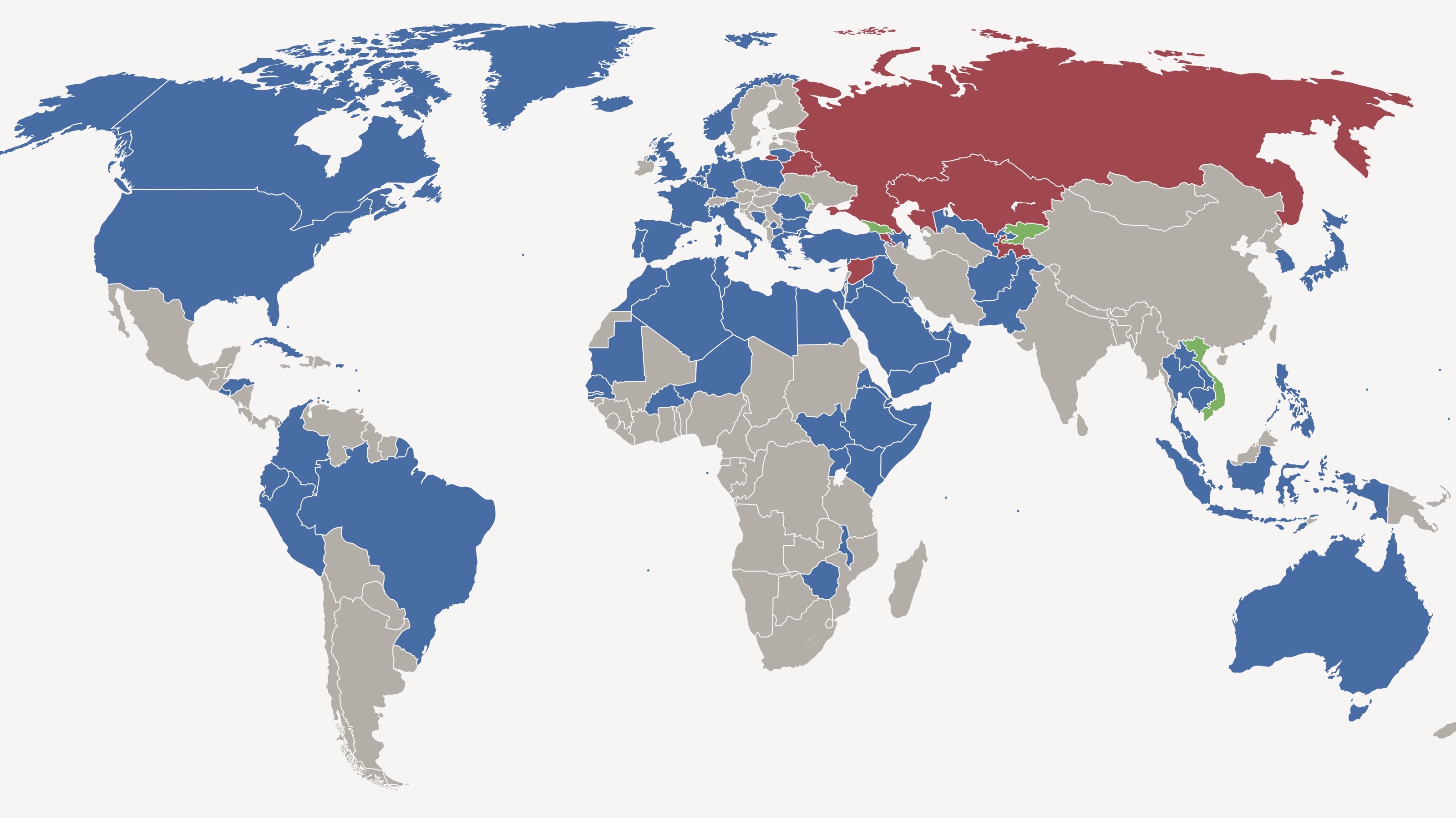

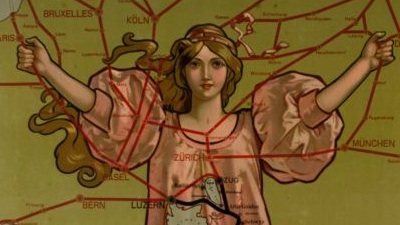

In the Second World War, the Swiss, completely surrounded by fascist forces (in fact, the only Axis-free country in continental Europe – except for that other Swiss-guarded European state, the Vatican), took precautions to ensure national survival in case of an Axis attack. They drew up plans for a Swiss National Redoubt, alternately called ‘Réduit suisse’ in French, and ‘Schweizer Réduit’ or ‘Alpenfestung’ in German.

The ‘Schweizer Réduit’ was similar in concept to other fortification chains constructed at that time in Europe: the Maginot-line by the French, the Siegfried-line by the Germans and others by the Czechoslovaks, Belgians and Dutch in the nineteen thirties. Those giant fortifications seem to prove the adage that armies are forever planning to fight the previous war: the chains of forts anticipate a static conflict such as the First World War and not the extremely mobile ‘Blitzkrieg’ that would be the hallmark of German conquests in Europe.

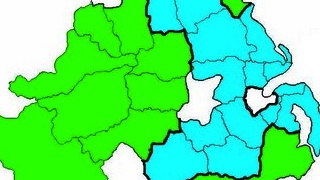

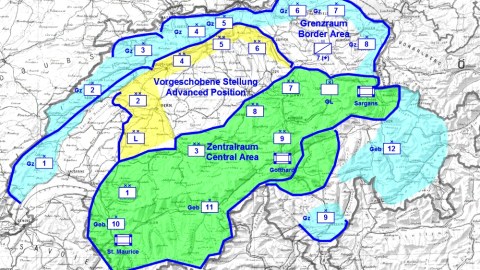

The Swiss national defence plan consisted of three stages: reinforcing the borders with new forts, preparing for a ‘Verzörgerungskrieg’ (delaying war) in the relatively level middle of the country and establishing an impregnable zone, the Réduit proper, in the high Alps. If necessary, roads and bridges would be destroyed to secure the Réduit. From this zone, Swiss sovereignty would have to be reestablished in occupied Switzerland after the war.

After the capitulation of France on July 12, 1940, Switzerland was entirely surrounded by Axis forces, and started finalising the Réduit. Impressed by the German Balkan campaign of April 1941, in which the Wehrmacht conquered Yugoslavia and Greece in a mere 23 days, the Swiss army high command further reinforced the Réduit by concentrating even more troops in it – effectively giving up the ‘Mittelland’, the economically and demographically most important lower-lying areas of central Switzerland.

By 1945, the Réduit’s construction had cost the equivalent of 406 million of today’s euros. Generally known to cover the most mountainous quarter of the territory (except most of the cantons of Graubünden and Tessin/Ticino), the exact borders of the Réduit remained a military secret until the mid-1990s.

The secrecy surrounding the Swiss alpine refuge gave rise to many rumours and legends, like the story about a top-secret military airstrip built into the mountainface, with an opening in the rock big enough to allow fighterplanes to exit and enter. Another story maintains mount Gotthard is so riddled with tunnels (like the proverbial Swiss cheese) that one could enter at Erstfeld in the north and emerge at Bodio in the south.

The Swiss national redoubt has contributed to the national self-image of Switzerland as a small, bravely defended island of peace amidst a sea of threats and wars. Post-1945, this national myth helped sustain the military doctrine of fortification as national defence against the communist threat. Yet the Réduit-strategy has also been criticised recently, as a capitulation to the Reich, sacrificing the big cities and large parts of the population to a German invasion.

This map taken here from Schweizer Daten 123. In yellow, the ‘delaying’ zone, ultimately to be abandoned. In green, the Réduit proper.

Strange Map #109

Got a strange map? Let me know at[email protected].