You Don’t Need A Scientific Hero To Love Science

As individuals, we scientists are all flawed. But the enterprise of science rises above our individual shortcomings.

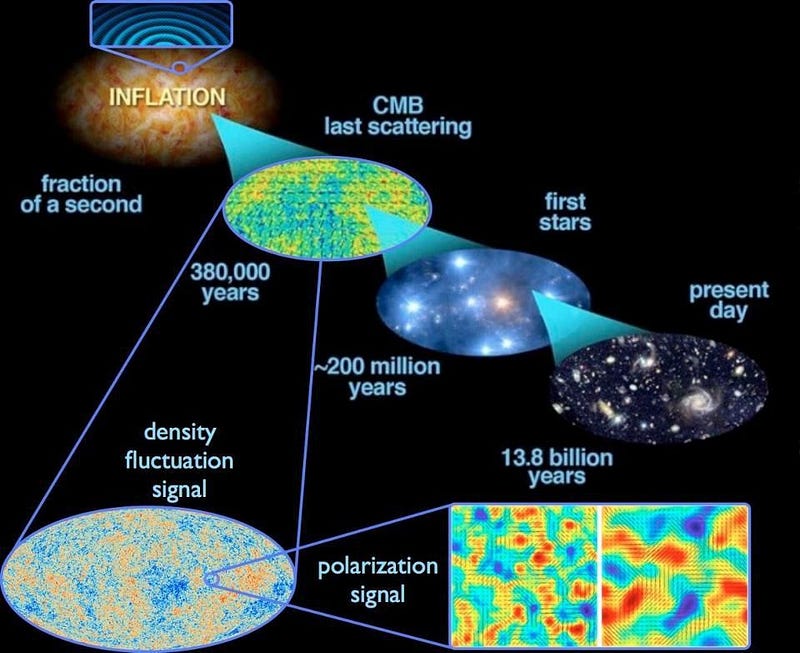

The enterprise of science is perhaps the greatest achievement in all of human history. Out of the seeming chaos of our terrestrial lives, we’ve managed to determine the fundamental, universal laws that underpin all of reality. We know what every macroscopic object is composed of, right down to the smallest indivisible particles that exist in nature. We understand the way they interact and can accurately describe the forces that arise between them.

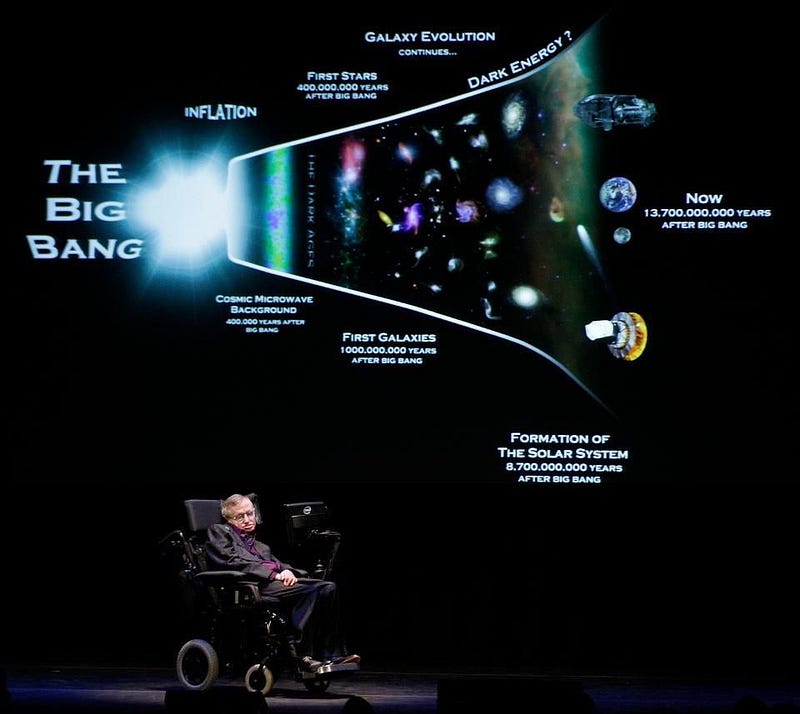

We know where the Universe came from, how it evolved to be the way it is today, and where it’s headed in the future. We know how planets form around stars, what the conditions are for life to arise, and once it begins, how it persists and evolves over billions of years. For the first time in human history, the question of where our physical reality comes from — a long-time question for philosophers, poets, and theologians — has been definitively answered: by science.

These achievements didn’t come about from just one person, no matter how intellectually gifted they were. Neither Newton nor Einstein nor Feynman nor Hawking knew it all. Moreover, all had serious flaws when it came to both their professional careers and their interpersonal conduct. While there are a great many figures who may be inspirational to you, personally, none of them can stand up to the wonders achieved by the enterprise of science itself.

The ability to investigate any natural phenomenon in a quantitative fashion — to subject it to scientific experiments, measurements, and observations in a controlled and well-calibrated fashion — enables us to understand how any physical system responds under a variety of conditions. By valuing and investing in that understanding, and applying what we learn to the policy decisions we make, we can build a society superior to the one we have now. In some ways, we’ve already gotten it right.

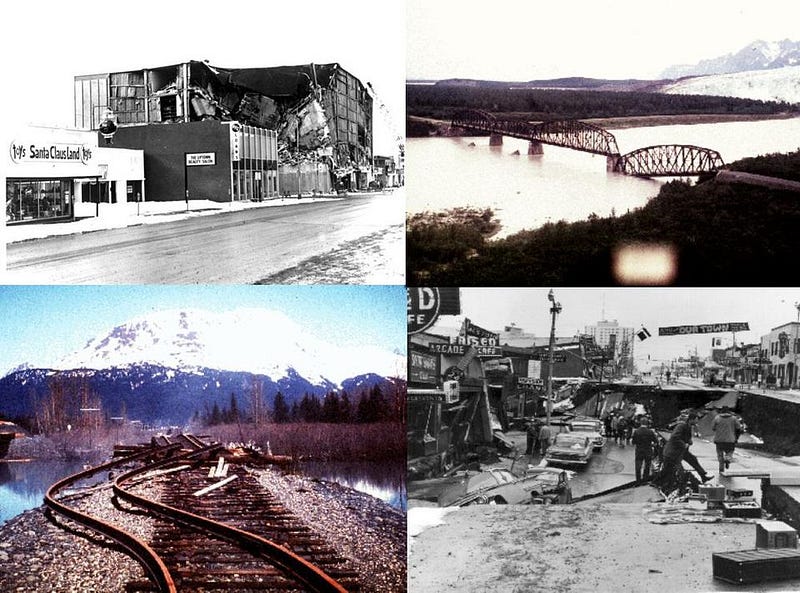

On November 30th, 2018, a potentially catastrophic earthquake struck Anchorage, Alaska. The magnitude 7.0 earthquake struck just 7 miles north of Anchorage, Alaska’s largest and most populous city. Roads were torn apart, buildings shook and rocked, ceilings fell and pipes broke, and much more. Major infrastructure damage, as well as severe damage to many homes and buildings, was well-documented. For a brief time, there was a tsunami warning as well, although that was canceled shortly thereafter.

And yet there was an incredible silver lining, despite more energy being released in this Earthquake than in the atomic bombs used against Japan in World War II. No one was killed. Despite all the property damage, the strength of the quake, and the close proximity of the epicenter to a city of approximately 300,000 people, there were no deaths from this earthquake. The reason why is a tremendous triumph of good science being used to make good policy.

Back in 1964, the largest recorded earthquake in North American history struck Prince William Sound in Alaska, reaching magnitude 9.2 on the Richter scale. The damage was catastrophic, but well-documented by the USGS. A total of 139 people died from that event, including the subsequent tsunami that caused fatalities as far away as California. While over $100 million in property damage was caused, a concerted rebuilding effort was made, the West Coast and Alaska Tsunami Warning Center was formed, and new codes were both put into place and enforced for construction.

But this time, the buildings in Anchorage were compliant with the revamped building codes. Advice was given (and heeded) as far as which locations must not be built on. Changes made in zoning and building codes, as directly informed by scientific findings, were instrumental to Anchorage’s resiliency in the face of a foreseeable natural disaster.

This is in stark contrast to many other locations which have failed to take those measures. The Hurricane Katrina disaster was as impactful as it was because there was no legislation to block the construction of residences at extreme risk for destruction in the event of a hurricane. California earthquakes, such as the Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 and the Northridge earthquake of 1994, were both lower-magnitude quakes than November’s Anchorage quake, but killed more than 50 apiece and resulted in billions in property damage.

Even more frighteningly, there’s an epidemic afflicting thousands of former coal miners: an advanced form of black lung disease. As NPR reports, regulators were absolutely poised to stop it: the risks were known, the information was easily available, and the science was overwhelming. But because we didn’t listen to it, thousands are suffering. Those afflicted are doomed to die a drawn-out, painful, debilitating death.

These two examples stand in stark contrast to one another. In the case of Anchorage, the risks were known, well-documented, and valued by the government. Legislation was written into law that made it illegal for citizens, industries, and corporations to take the risky actions that would surely result in excessive property damage and loss of life when the inevitable occurred. While individuals like USGS’s Bill Leith were instrumental in crafting scientifically-sound policy recommendations, it took a slew of individuals all working together to turn those recommendations into law.

Yet in many more cases, those recommendations are ignored, shouted down, or countered with a disinformation campaign. When confusion and doubt can be successfully sown, science can be devalued in favor of other interests. In many cases, from public safety to agricultural practices to the management of our environment and Earth’s natural resources, this is arguably humanity’s norm.

Aspiring to work in science means you aspire to increase the knowledge and understanding we have of the world and Universe around us. An increase in human knowledge must always be appreciated, even if the knowledge we gain runs counter to what we hoped to discover. Science means challenging your assumptions, taking nothing for granted, and constantly doubting and re-evaluating your conclusions in the face of the ever-growing suite of data available.

In a society that valued science, this would translate into policies that were well-informed by science. Whenever there’s a policy decision to be made, accepting the scientific facts of a situation ought to be a prerequisite for getting a seat at the table. One may not always value the scientific interest over the economic or human interests that will be impacted, but devaluing science doesn’t make it less true. We ignore it at our own peril, and quite often, to our own detriment.

Science also requires care, as it’s very easy to devise a theory that looks compelling, powerful, and yet that turns out to be woefully incorrect. It’s part of the scientific method to exhaustively attempt to identify every possible source of error, bias, or confounding factor that may be present whenever we study any natural phenomenon.

Yet science itself is inherently a human endeavor, and is therefore easily biased by our own individual failings. Newton may have been an influential genius, but his distaste for the wave theory of light set our advances back in that arena by generations. Einstein may have been the most brilliant scientist of them all, but his failure to accept our quantum reality as it truly is still impacts many scientists today. As far as science brings us, the failings of every single influential scientist become apparent on any sort of close examination.

And yet, this doesn’t detract from people’s need for role models: people you can look up to. Some people go a step further and seek heroes: people they admire, idolize, or even wish they could be.

There isn’t anything inherently wrong with having a hero, but not all of us do.

Adopting a hero should come with a caveat that implores us not to deify them, as no one has lived a life free from flaws or errors. Otherwise, we risk emulating not only their great successes, but their great failures and shortcomings as well. This is true for any figure you could imagine, from Freud to Feynman to Hawking and beyond.

It should be science itself, however, that we save our greatest admiration for. It’s more than a suite of facts, although it encompasses everything we know, observe, measure, or experience. It’s more than a process that self-corrects and re-evaluates itself in the face of new evidence, although it certainly encompasses that.

It is how we arrive at our best approximation for reality itself. Science takes us as close as we’ve ever been to understanding the entire Universe. We should all hope to not only be aware of what science is and how it works, but also to appreciate how science has bettered our lives, perhaps moreso than any other human development.

Many of us who don’t have heroes to look up to often feel inadequate: like there’s something lacking in us because of it. But it’s far better to go on that quest of self-discovery and become the best version of yourself you can be, as opposed to a cheap imitation of someone else’s best version of themselves. Don’t strive to become the next Einstein, Tesla, Curie, or Witten; if you do, you’ll doom yourself to the same failings that they encounter(ed) in their lives.

Instead, in science and beyond, we must learn to rely on more than just ourselves. We must adopt the full suite of knowledge that we possess at any given time, and make the best decisions we can based on that information, even — and perhaps especially — when it offends our sensibilities. Progress is neither easy nor swift, and humanity inevitably draws more good than evil from new discoveries.

We must listen to the story nature tells us about itself, and scientific investigation is how we do it. May we be humble enough to let that be the real hero that we follow in this life.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.