Weekend Diversion: Had NASA believed in merit

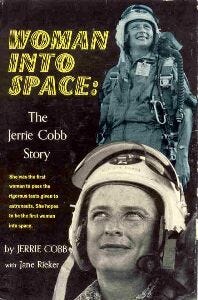

The terrible injustice of Jerrie Cobb, who deserved to be the first female astronaut, yet never made it to space at all.

Image credit: © 2011 501(c)(3) Non Profit National Aviation Hall of Fame.

“I would give my life to fly in space. It’s hard for me to talk about it but I would. I would then, and I will now.” –Jerrie Cobb, at age 67 in 1999

There are some stories that have truly captured the collective imagination of the world, and a great many of them — understandably — involve humanity’s first steps into space. The first seven American astronauts, dubbed the Mercury 7, were: Alan Shepard, Gus Grissom, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, Wally Schirra, Gordon Cooper, and Deke Slayton.

Although they were certainly deserving, well-qualified and capable, there was a better candidate than many of these men who was passed over for all the wrong reasons. Have a listen to Railroad Earth’s incredible composition about a bird that can’t fly free or sing its song, Bird In A House,

while I share with you the story of the one should-have-been astronaut who never got the chance: Jerrie Cobb.

Imagine the scene: in 1957, Sputnik 1 was launched into space, and became the first artificial satellite orbiting our world. The space race had begun, with human spaceflight and manned missions to leave our world the next great achievement to strive for. For 26 year old Jerrie Cobb, it seemed like the perfect fit.

Born in 1931, she had taken her first flight at the age of 12 in her father’s plane, and she was hooked. Striving for the highest of heights, the loftiest of altitudes and the achievements of soaring — using the aid of any technological resources at her disposal — wherever she could reach under her own power, control and skill set, she knew she wanted to be a pilot. By time she was 17 she had her Private Pilot’s License, the next year she earned her Commercial Pilot’s License and gained her Flight Instructor’s Rating shortly thereafter. In 1949, she was awarded the Amelia Earhart Gold Medal of Achievement.

But the 1950s weren’t kind to women looking for a career in aviation: flight attendants and other “women-only” roles were pretty much it. Not being ready to give up on her dreams, she took a job at the Miami airport in Florida where she met a former World War II pilot, Jack Ford, who had a service that ferried aircrafts all around the world. It wasn’t long before she talked him into a job, and not only proved herself up to the challenge, but distinguished herself as one of the top pilots of performance aircraft of the 1950s. She became the first woman to fly in the Paris Air show, after which she was named Pilot of the Year. Shortly thereafter, she set aviation world records for the following:

- the world light plane speed record (set in 1959),

- the world record for nonstop long-distance flight (also 1959), and

- the world altitude record for lightweight aircraft of 37,010 ft (1960), breaking her own, earlier record from 1957.

It was no surprise, then, that she received a special invitation to the Lovelace Clinic in Albuquerque, NM.

And for those of you who don’t know, the Lovelace Clinic was the very location where the applicants for the very first astronauts reported for training, testing and, eventually, selection. The original NASA astronaut stipulation was that the applicants needed to be military test pilots, which excluded women. There were originally 508 applicants, of which 110 were invited for interviews. The Lovelace Clinic was where a series of physical and mental tests — developed by William Randolph Lovelace II — were performed on the candidates to determine their fitness for space. The first crew, the aforementioned Mercury 7, were chosen from among the top performers.

But about a year later, Lovelace became curious about how women would perform on this same test, and whether they would, perhaps, be equally well-suited for space?

Thirteen American women — today known as the Mercury 13 — were selected to participate in the three phases of testing. Jerrie Cobb was the only one who passed them all. Not only did she pass, her scores placed her in the top 2% of all candidates, meaning that if the same criteria that were applied to the Mercury 7 were applied to her as well, she would have been selected. But without official NASA backing, the testing and training programs for women were shut down.

In 1963, Cobb went to Washington DC to testify at a congressional hearing about women astronauts. Despite having more than 7,000 hours of flight experience, she was not an official military test pilot, and only one of her flights took place in a jet aircraft; all the rest were in propellor-powered planes, of which she had flown sixty-four different types at the time. Despite the testimony of many advocating that women were just as fit for spaceflight as men, including John Glenn, who stated,

[M]en go off and fight the wars and fly the airplanes […] The fact that women are not in this field is a fact of our social order.

Despite the fact that exceptions had been made for other astronauts who didn’t meet all the prerequisite requirements (including Glenn himself), one was not granted for Cobb. A letter was drafted that questioned the requirements and made it as far as (then Vice-President) Lyndon Johnson’s desk, but was never sent to NASA. Later that year, Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space for the USSR. Meanwhile, NASA wouldn’t open its astronaut ranks to women until 1978.

After working as a consultant for NASA for a brief time, Cobb quit, feeling that she was having no impact at all and that she wasn’t in the one place she needed to be the most: the skies. She scrounged up an old twin-engine Aero Commander, and spent the next thirty years flying peaceful supply missions to South America, even being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1981 for her humanitarian efforts. She has been honored by the governments of five countries for her work: Brazil, France, Ecuador, Colombia and Peru.

In 1999, there was a campaign to finally send her into space, similar to the one that sent John Glenn into space to study the effects of spaceflight on aging and aged individuals. At 67, she would have been the oldest woman ever to fly in space. The campaign failed, and as of today, in 2014, Jerrie Cobb has still never left the bonds of Earth.

Two years ago, she was inducted into the United States National Aviation Hall Of Fame, her most recent accolade. But when I think of her, I think of the one thing she said that should resonate with anyone following their lifelong passion:

“I have a feeling that life is a spiritual adventure, and I want to make mine in the sky… it’s what I was born to do, my life won’t be complete until I fly in space.”

You deserve it, Jerrie. And at 83, you deserve the admiration of the entire world. Hopefully, it’s still not too late to achieve your greatest dream.

Read more about Jerrie Cobb at the Mercury 13 site, at the Jerrie Cobb Foundation, and a brief biography of her here. And leave your comments to this article at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs.