We Have Now Reached The Limits Of The Hubble Space Telescope

The world’s greatest observatory can go no further with its current instrument set.

The Hubble Space Telescope has provided humanity with our deepest views of the Universe ever. It has revealed fainter, younger, less-evolved, and more distant stars, galaxies, and galaxy clusters than any other observatory. More than 29 years after its launch, Hubble is still the greatest tool we have for exploring the farthest reaches of the Universe. Wherever astrophysical objects emit starlight, no observatory is better equipped to study them than Hubble.

But there are limits to what any observatory can see, even Hubble. It’s limited by the size of its mirror, the quality of its instruments, its temperature and wavelength range, and the most universal limiting factor inherent to any astronomical observation: time. Over the past few years, Hubble has released some of the greatest images humanity has ever seen. But it’s unlikely to ever do better; it’s reached its absolute limit. Here’s the story.

From its location in space, approximately 540 kilometers (336 mi) up, the Hubble Space Telescope has an enormous advantage over ground-based telescopes: it doesn’t have to contend with Earth’s atmosphere. The moving particles making up Earth’s atmosphere provide a turbulent medium that distorts the path of any incoming light, while simultaneously containing molecules that prevent certain wavelengths of light from passing through it entirely.

While ground-based telescopes at the time could achieve practical resolutions no better than 0.5–1.0 arcseconds, where 1 arcsecond is 1/3600th of a degree, Hubble — once the flaw with its primary mirror was corrected — immediately delivered resolutions down to the theoretical diffraction limit for a telescope of its size: 0.05 arcseconds. Almost instantly, our views of the Universe were sharper than ever before.

Sharpness, or resolution, is one of the most important factors in discovering what’s out there in the distant Universe. But there are three others that are just as essential:

- the amount of light-gathering power you have, needed to view the faintest objects possible,

- the field-of-view of your telescope, enabling you to observe a larger number of objects,

- and the wavelength range you’re capable of probing, as the observed light’s wavelength depends the object’s distance from you.

Hubble may be great at all of these, but it also possesses fundamental limits for all four.

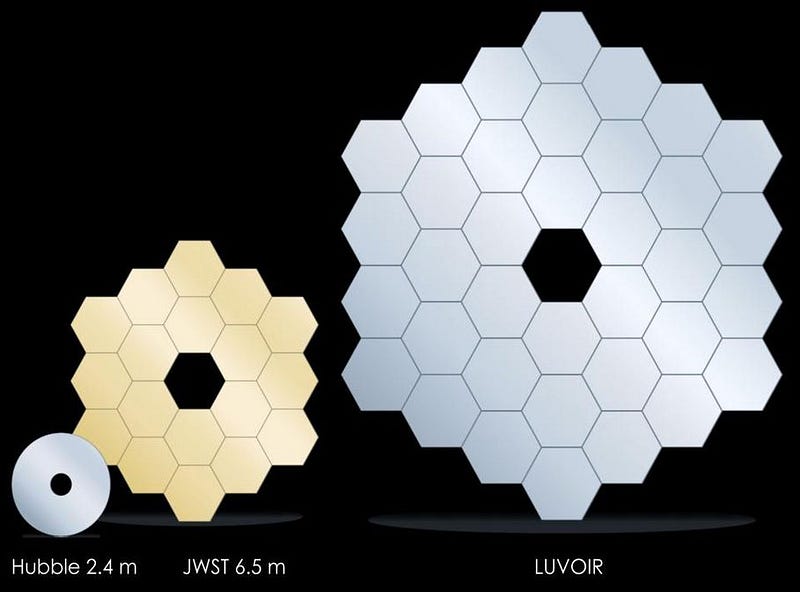

The resolution of any telescope is determined by the number of wavelengths of light that can fit across its primary mirror. Hubble’s 2.4 meter (7.9 foot) mirror enables it to obtain that diffraction-limited resolution of 0.05 arcseconds. This is so good that only in the past few years have Earth’s most powerful telescopes, often more than four times as large and equipped with state-of-the-art adaptive optics systems, been able to compete.

To improve upon the resolution of Hubble, there are really only two options available:

- use shorter wavelengths of light, so that a greater number of wavelengths can fit across a mirror of the same size,

- or build a larger telescope, which will also enable a greater number of wavelengths to fit across your mirror.

Hubble’s optics are designed to view ultraviolet light, visible light, and near-infrared light, with sensitivities ranging from approximately 100 nanometers to 1.8 microns in wavelength. It can do no better with its current instruments, which were installed during the final servicing mission back in 2009.

Light-gathering power is simply about collecting more and more light over a greater period of time, and Hubble has been mind-blowing in that regard. Without the atmosphere to contend with or the Earth’s rotation to worry about, Hubble can simply point to an interesting spot in the sky, apply whichever color/wavelength filter is desired, and take an observation. These observations can then be stacked — or added together — to produce a deep, long-exposure image.

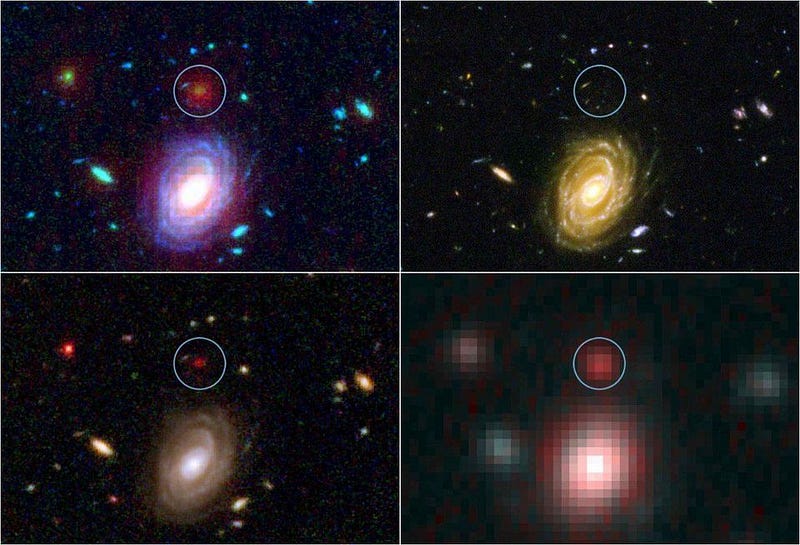

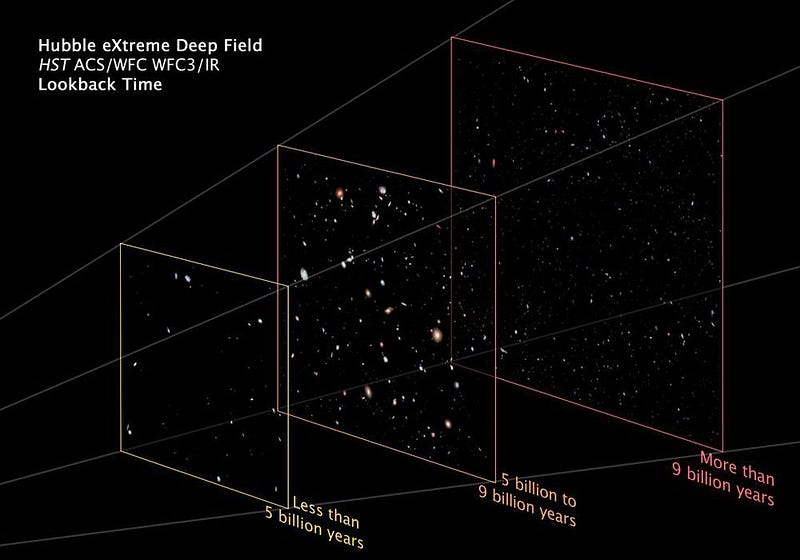

Using this technique, we can see the distant Universe to unprecedented depths and faintnesses. The Hubble Deep Field was the first demonstration of this technique, revealing thousands of galaxies in a region of space where zero were previously known. At present, the eXtreme Deep Field (XDF) is the deepest ultraviolet-visible-infrared composite, revealing some 5,500 galaxies in a region covering just 1/32,000,000th of the full sky.

Of course, it took 23 days of total data taking to collect the information contained within the XDF. To reveal objects with half the brightness as the faintest objects seen in the XDF, we’d have to continue observing for a total of 92 days: four times as long. There’s a severe trade-off if we were to do this, as it would tie up the telescope for months and would only teach us marginally more about the distant Universe.

Instead, an alternative strategy for learning more about the distant Universe is to survey a targeted, wide-field area of the sky. Individual galaxies and larger structures like galaxy clusters can be probed with deep but large-area views, revealing a tremendous level of detail about what’s present at the greatest distances of all. Instead of using our observing time to go deeper, we can still go very deep, but cast a much wider net.

This, too, comes with a tremendous cost. The deepest, widest view of the Universe ever assembled by Hubble took over 250 days of telescope time, and was stitched together from nearly 7,500 individual exposures. While this new Hubble Legacy Field is great for extragalactic astronomy, it still only reveals 265,000 galaxies over a region of sky smaller than that covered by the full Moon.

Hubble was designed to go deep, but not to go wide. Its field of view is extremely narrow, which makes a larger, more comprehensive survey of the distant Universe all but prohibitive. It’s truly remarkable how far Hubble has taken us in terms of resolution, survey depth, and field-of-view, but Hubble has truly reached its limit on those fronts.

Finally, there are the wavelength limits as well. Stars emits a wide variety of light, from the ultraviolet through the optical and into the infrared. It’s no coincidence that this is what Hubble was designed for: to look for light that’s of the same variety and wavelengths that we know stars emit.

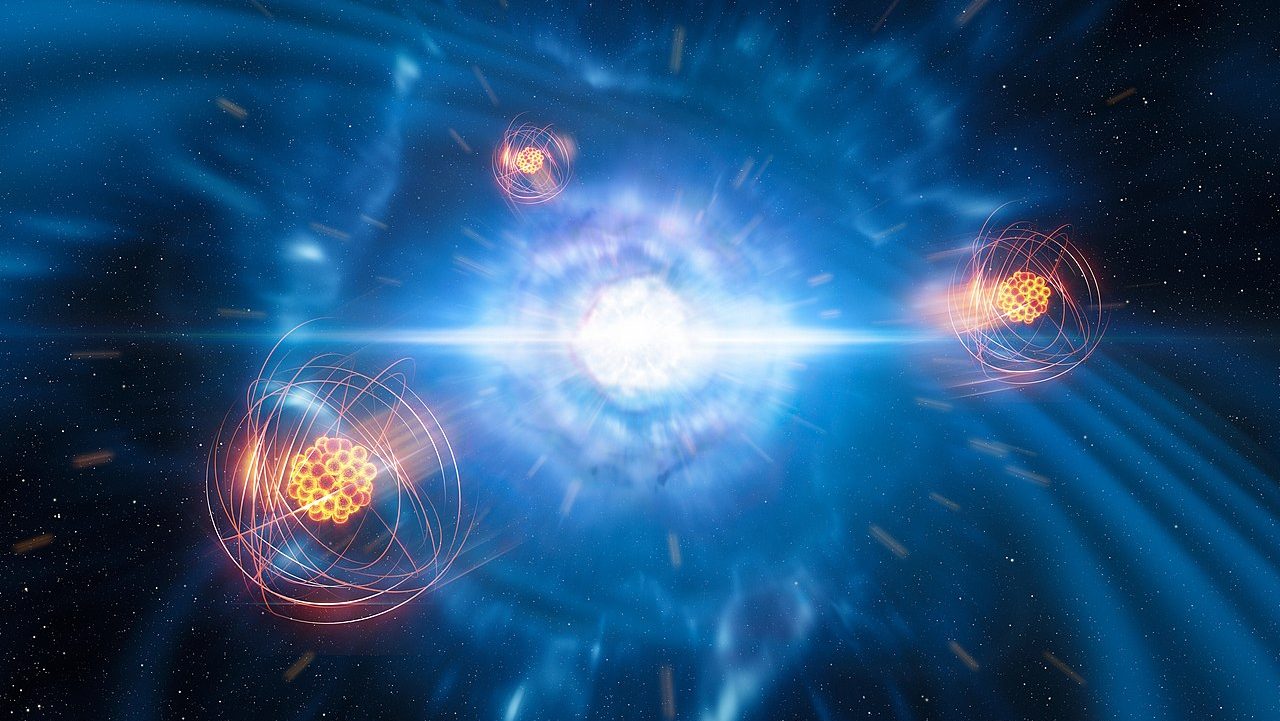

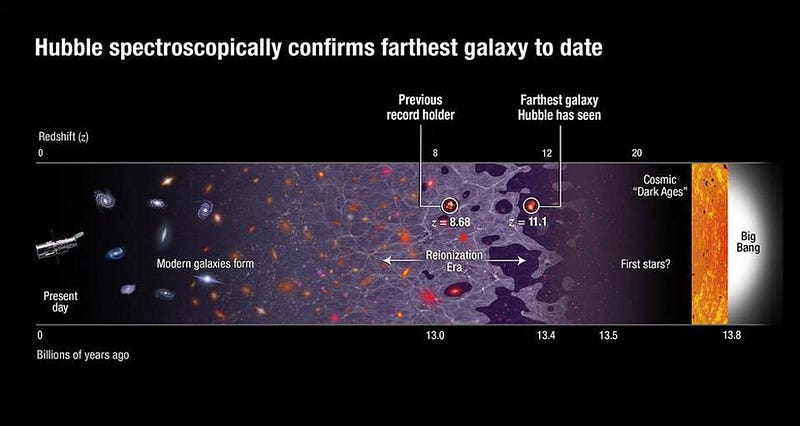

But this, too, is fundamentally limiting. You see, as light travels through the Universe, the fabric of space itself is expanding. This causes the light, even if it’s emitted with intrinsically short wavelengths, to have its wavelength stretched by the expansion of space. By the time it arrives at our eyes, it’s redshifted by a particular factor that’s determined by the expansion rate of the Universe and the object’s distance from us.

Hubble’s wavelength range sets a fundamental limit to how far back we can see: to when the Universe is around 400 million years old, but no earlier.

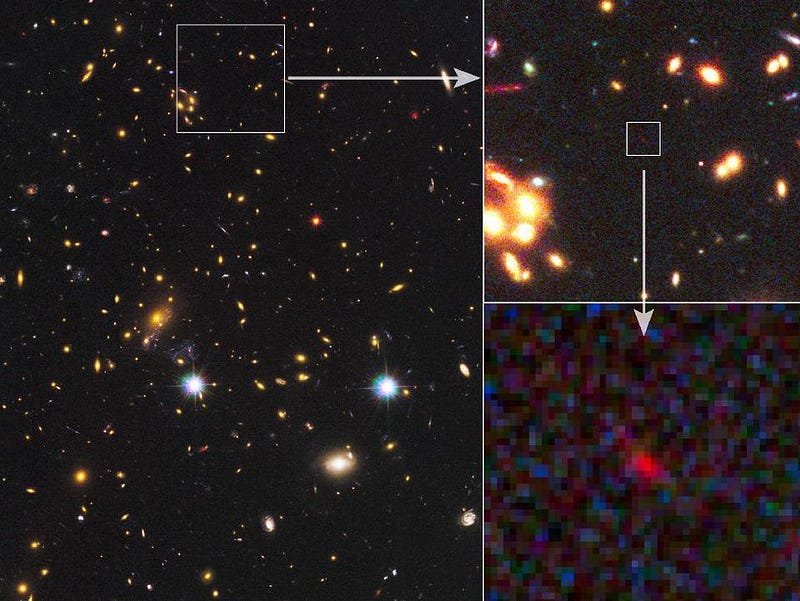

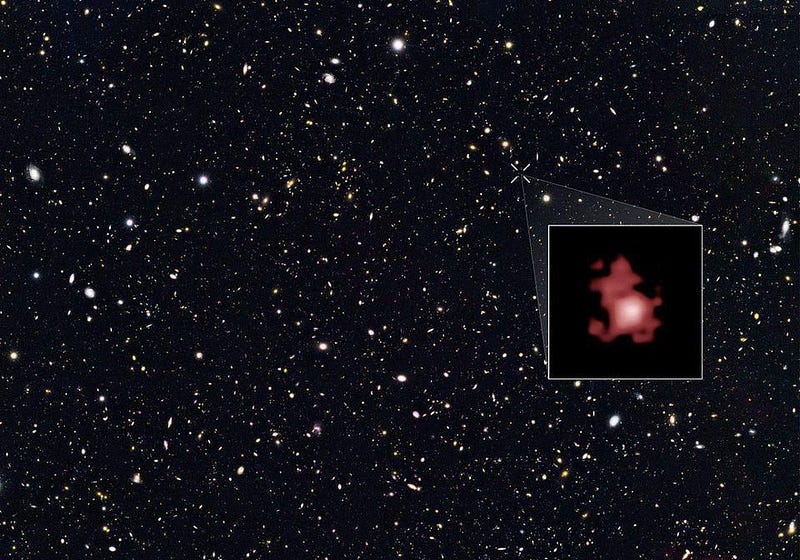

The most distant galaxy ever discovered by Hubble, GN-z11, is right at this limit. Discovered in one of the deep-field images, it has everything imaginable going for it.

- It was observed across all the different wavelength ranges Hubble is capable of, with only its ultraviolet-emitted light showing up in the longest-wavelength infrared filters Hubble can measure.

- It was gravitationally lensed by a nearby galaxy, magnifying its brightness to raise it above Hubble’s naturally-limiting faintness threshold.

- It happens to be located along a line-of-sight that experienced a high (and statistically-unlikely) level of star-formation at early times, providing a clear path for the emitted light to travel along without being blocked.

No other galaxy has been discovered and confirmed at even close to the same distance as this object.

Hubble may have reached its limits, but future observatories will take us far beyond what Hubble’s limits are. The James Webb Space Telescope is not only larger — with a primary mirror diameter of 6.5 meters (as opposed to Hubble’s 2.4 meters) — but operates at far cooler temperatures, enabling it to view longer wavelengths.

At these longer wavelengths, up to 30 microns (as opposed to Hubble’s 1.8), James Webb will be able to see through the light-blocking dust that hampers Hubble’s view of most of the Universe. Additionally, it will be able to see objects with much greater redshifts and earlier lookback times: seeing the Universe when it was a mere 200 million years old. While Hubble might reveal some extremely early galaxies, James Webb might reveal them as they’re in the process of forming for the very first time.

Other observatories will take us to other frontiers in realms where Hubble is only scratching the surface. NASA’s proposed flagship of the 2020s, WFIRST, will be very similar to Hubble, but will have 50 times the field-of-view, making it ideal for large surveys. Telescopes like the LSST will cover nearly the entire sky, with resolutions comparable to what Hubble achieves, albeit with shorter observing times. And future ground-based observatories like GMT or ELT, which will usher in the era of 30-meter-class telescopes, might finally surpass Hubble in terms of practical resolution.

At the limits of what Hubble is capable of, it’s still extending our views into the distant Universe, and providing the data that enables astronomers to push the frontiers of what is known. But to truly go farther, we need better tools. If we truly value learning the secrets of the Universe, including what it’s made of, how it came to be the way it is today, and what its fate is, there’s no substitute for the next generation of observatories.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.