How we know the Universe is 13.8 billion years old

- If we count from the start of the hot Big Bang, we learn that the Universe is 13.8 billion years old, with only a very tiny (~1%) degree of uncertainty.

- But what gives us the right to call the start of the hot Big Bang “the beginning,” particularly if we now can confidently state that a period of cosmic inflation preceded it?

- The reality is that we have to make choices, and the start of the hot Big Bang is one of the earliest things we can be certain about. Here’s what the “age of the Universe” actually means.

According to the theory of the hot Big Bang, the Universe had a beginning. Originally known as “a day without a yesterday,” this is one of the most controversial, philosophically mind-blowing pieces of information we’ve come to accept as part of the scientific history of our Universe. Many detractors will reject it as being too in-line with certain religious texts, while others — perhaps more justifiably — note that in the modern context of cosmic inflation, the hot Big Bang only occurred as the aftermath of a previous epoch.

And yet, if you ask any cosmologist or astrophysicist who’s well-versed in the scientific story of our beginnings “How old is our Universe?” you always get the same answer: 13.8 billion years. Why is this, and when do we start counting? That’s what Denis Gaudet wanted to know, having written in to ask:

“Why do you start counting the age of the universe after 380,000 years have elapsed after the Big Bang?”

The time “380,000 years after the Big Bang” is of particular interest, but very few people mark that as the beginning of the Universe; it is the beginning of something important, however. Here’s what we can say about how old our Universe truly is.

The first thing you need to understand is that there are two different ways of measuring the age of the Universe since the start of the hot Big Bang.

- We can find “the oldest thing we know how to measure its age” and conclude that the Universe must be at least that old.

- We can use what we know about the theory that governs the Universe, general relativity, as well as our knowledge of what the Universe is made out of plus how fast it’s expanding today to calculate how long it’s been since the start of the hot Big Bang.

The first method isn’t exactly a measurement of how old the Universe is, but rather a sanity check: the Universe cannot be younger than the things in it, so when we find things in it and measure their ages, we conclude that the Universe must be at least that old.

As cosmology and astrophysics grew out of the far older sciences of astronomy and physics, it should come as no surprise that one of the things we’ve gotten very good at knowing the ages of are stars and large populations of stars. Here’s how that works.

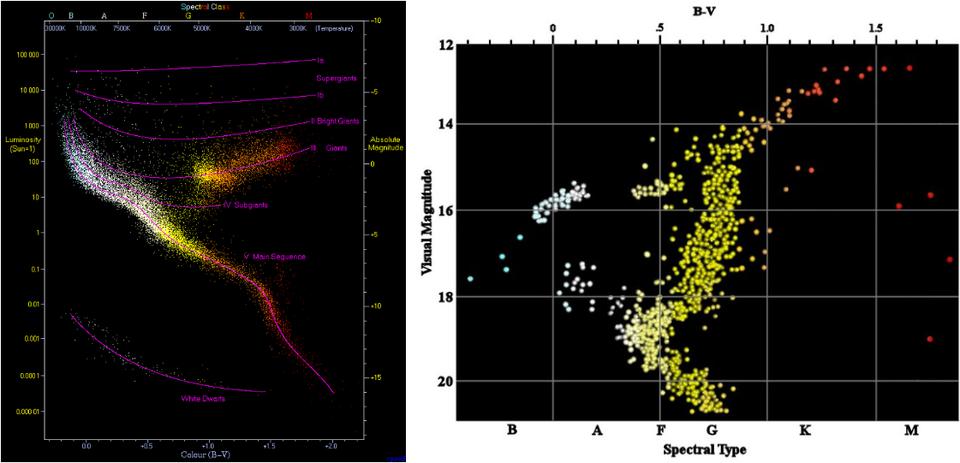

Whenever and wherever stars are born, which occurs whenever clouds of gas sufficiently collapse under their own gravity, they come in a wide variety of sizes, colors, temperatures, and masses. The largest, bluest, most massive stars contain the greatest amounts of nuclear fuel, but perhaps paradoxically, those stars are actually the shortest lived. The reason is straightforward: in any star’s core, where nuclear fusion occurs, it only occurs wherever temperatures exceed 4 million K, and the higher the temperature, the greater the rate of fusion.

So the most massive stars might have the most fuel available at the start, but that means they shine brightly as they burn through their fuel quickly. In particular, the hottest regions in the core will exhaust their fuel the fastest, leading the most massive stars to die the most quickly. The best method we have for measuring “How old is a collection of stars?” is to examine globular clusters, which form stars in isolation often all at once, and then never again. By looking at the cooler, fainter stars that remain (and the lack of hotter, bluer, brighter, more massive stars), we can state with confidence that the Universe must be at least ~12.5-13.0 billion years old.

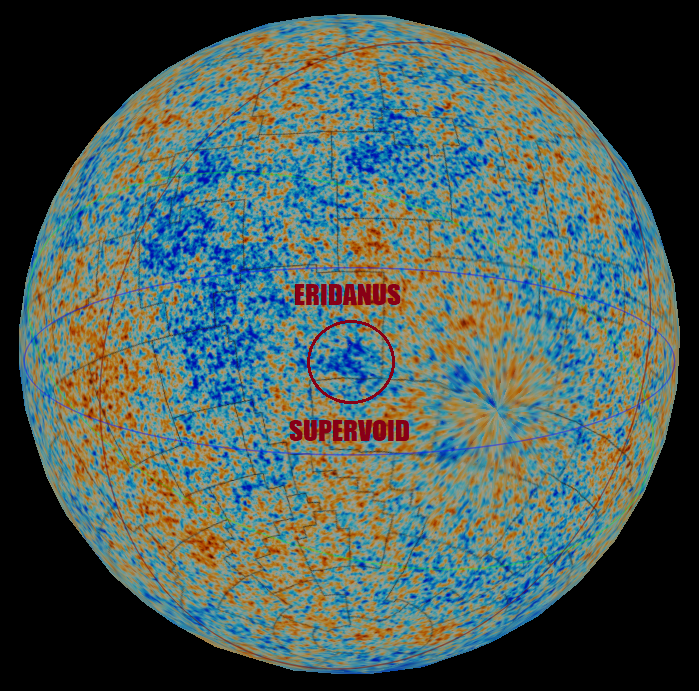

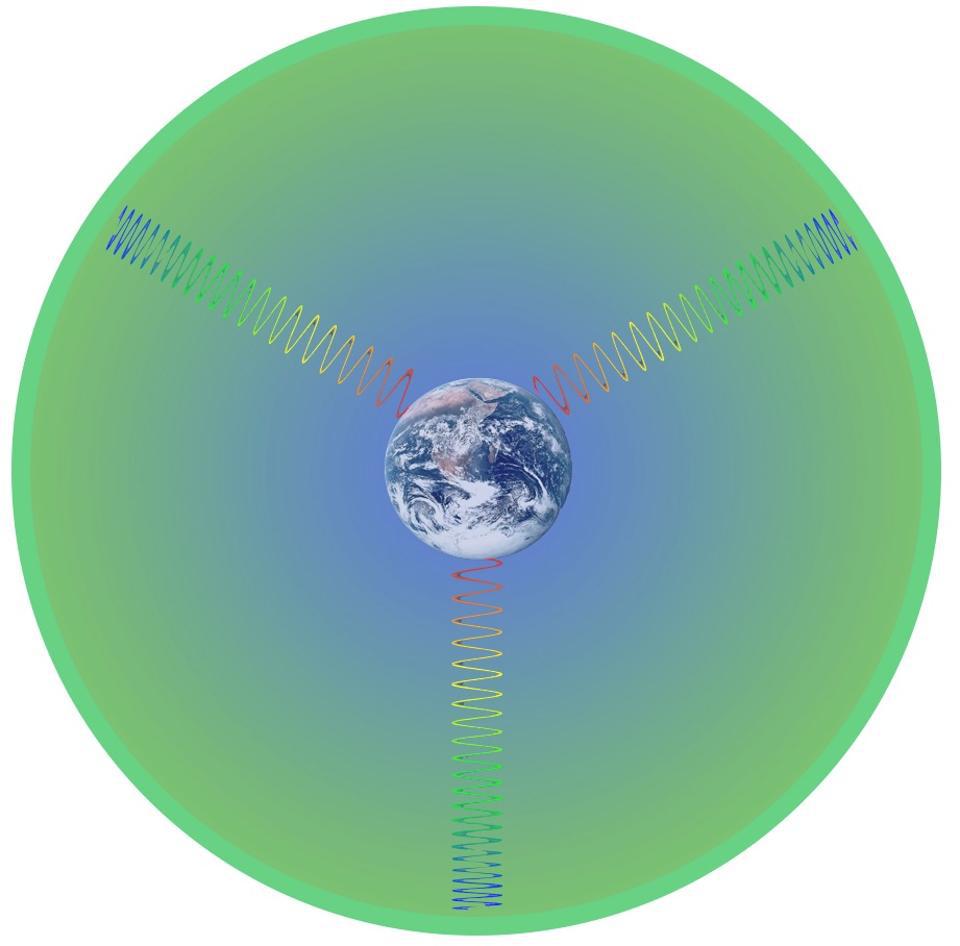

Similarly, we can take the known laws of physics, like general relativity, and apply them to the expanding Universe. That results in a set of equations — the Friedmann equations — that relate how the Universe has expanded over its history to how fast it’s expanding today and also the various forms of energy that are present inside of it. When we take the best suite of data that’s available, including from the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is made of the light left over from the Big Bang, and from all the large-scale clustering data we’ve collected, we get a straightforward answer that reveals our cosmic history to us.

We find that the Universe is made of:

- 68% dark energy,

- 27% dark matter,

- 4.9% normal matter,

- 0.1% neutrinos,

- 0.01% photons,

and not an appreciable amount of anything else. We also find that it’s expanding at a rate of 67 km/s/Mpc, which — when we combine all that information together — reveals a Universe that’s 13.8 billion years old, if we extrapolate all the way back to the instant of the Big Bang. Case closed?

Not entirely. There are three objections you can make, each with varying degrees of validity.

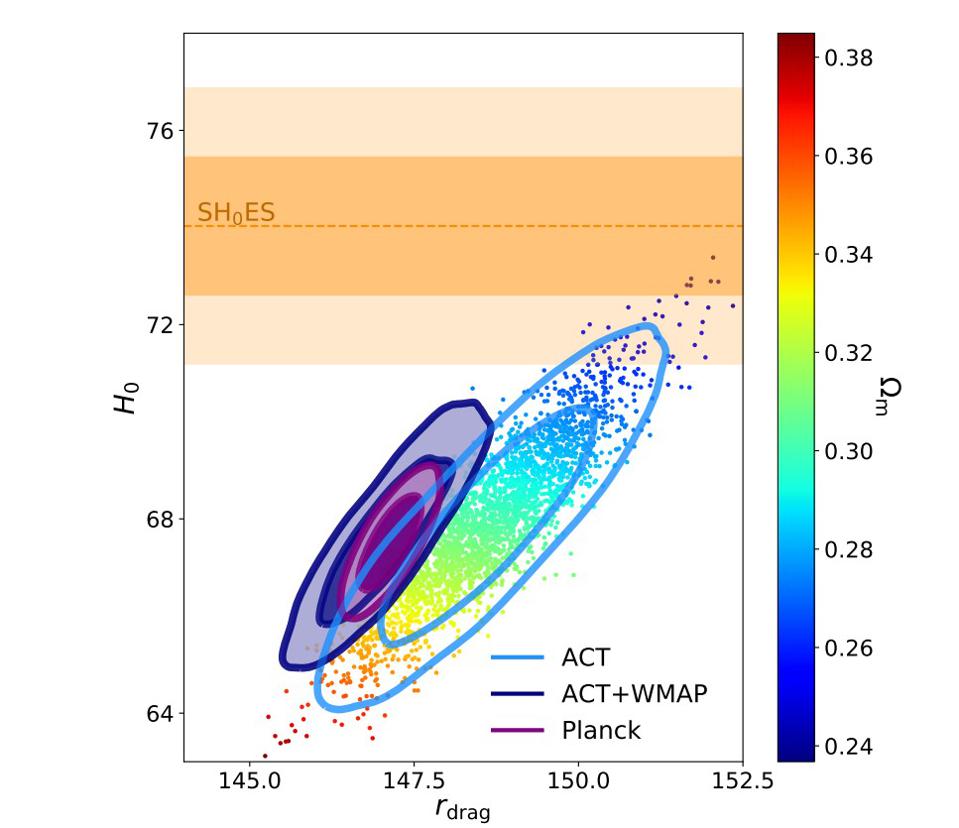

Objection #1: What about the Hubble tension, or the fact that different measurement methods give a value for the expansion rate that’s 74 km/s/Mpc, or 9% greater than the value quoted?

It’s true: if we measure an imprint from the early Universe, like how far away different maximal “peaks” in density are from one another in the expanding Universe, we get the earlier value of 67 km/s/Mpc with the Universe’s constituents mentioned above. But what if that method isn’t correct, or isn’t universally correct, and the late-time methods we use, such as the cosmic distance ladder, which give 74 km/s/Mpc, is correct instead?

You might think that this would imply a younger Universe, as “faster expansion” means it takes less time to trace the Universe back to a condition where all the matter and energy was shrunk down to a single point.

But it turns out there are degeneracies between various parameters in terms of “what makes up the Universe” and “how fast is the Universe expanding,” meaning that if the expansion rate is 9% greater, that forces us to slightly increase the amount of dark energy by a few percent, at the expense of dark matter, which decreases by about the same amount. The “age of the Universe” might shift a little bit, perhaps down to 13.6 billion years, but that’s not by very much at all. The “age” parameter is largely invariant to these changes.

Objection #2: Should we start counting from 380,000 years, where the CMB we observe was emitted, or some other milestone, instead of a nominal “t=0” corresponding to the moment of the Big Bang?

This is an interesting consideration, because it makes sense only to extrapolate as far back as your data allows you to be certain that the extrapolation is valid. However, there are two reasons why I wouldn’t only go all the way back to the CMB.

- We have two sets of signals that go back farther: the abundance of the light elements created from Big Bang nucleosynthesis, which takes place when only 3-4 minutes have elapsed since the hot Big Bang, and the signals from the cosmic neutrino background that imprint themselves into the CMB and the large-scale structure of the Universe, which were created and frozen-in when only ~1 second had elapsed since the hot Big Bang.

- When we count back billions of years — you know, 13.8 billion years — the uncertainty is in the last digit: the “8” in 13.8 billion. If you’re off by 380,000 years, or a few minutes or seconds for that matter, you won’t notice; that’s not significant compared to the 13.8 billion figure.

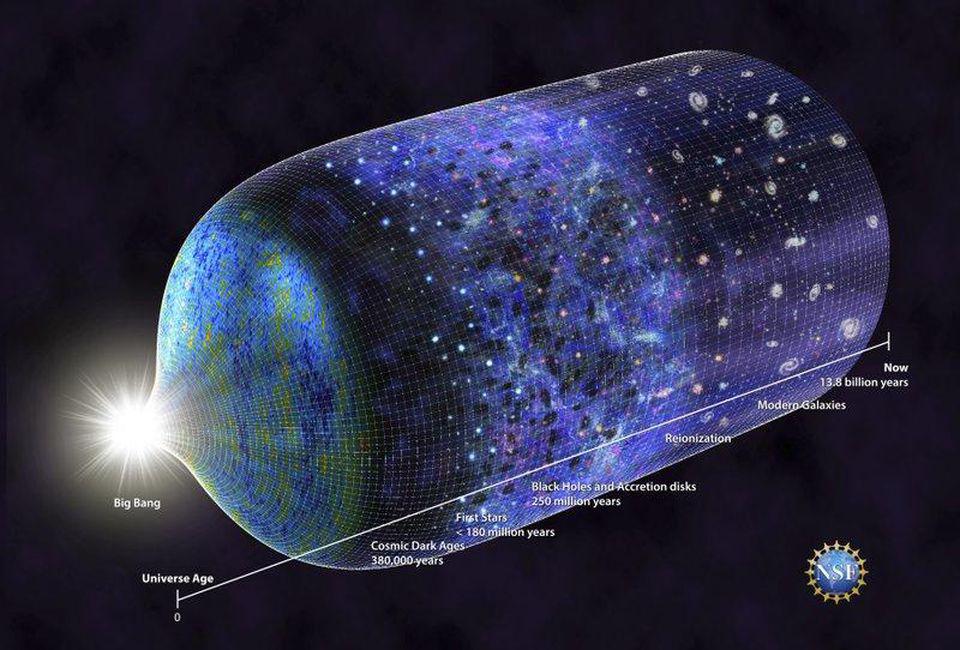

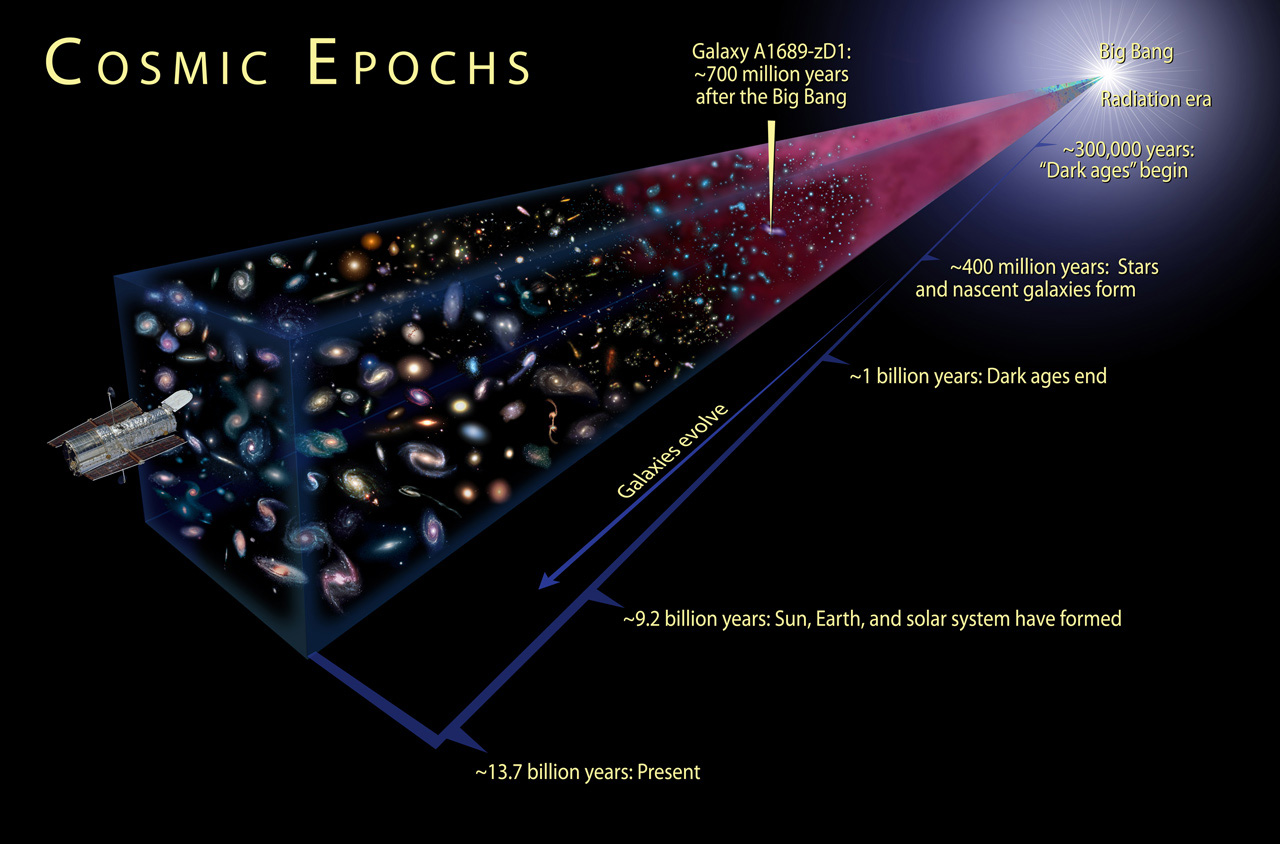

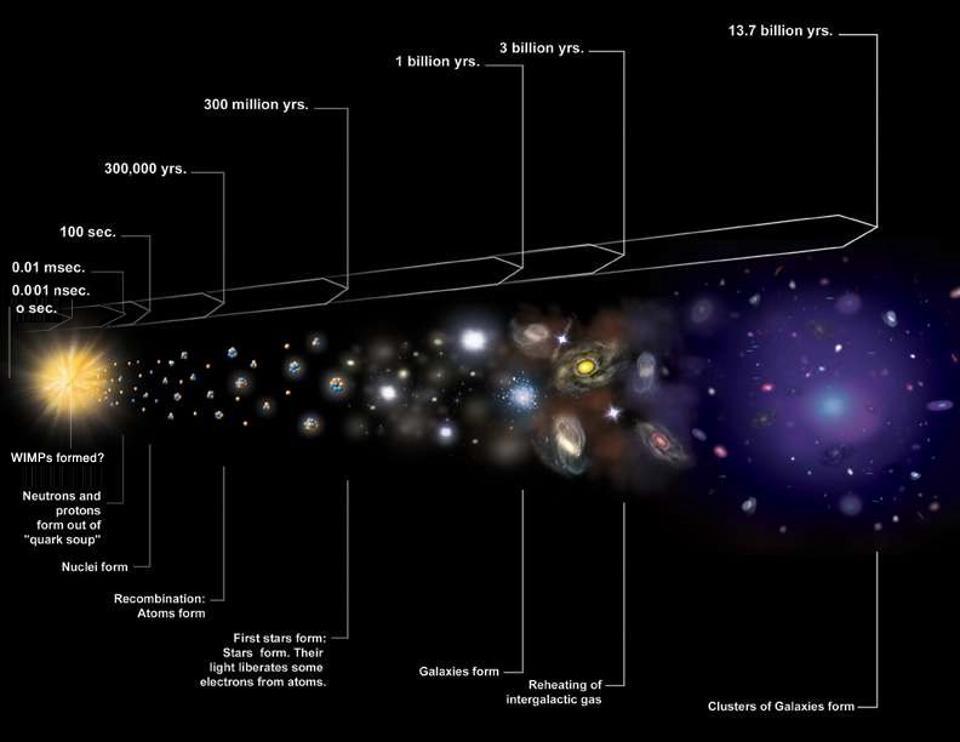

It’s true that there are many milestones that we can reach extrapolating back in time: the first galaxy clusters, the first galaxies, the first stars, the first neutral atoms, the first stable atomic nuclei, the first protons-and-neutrons, the first massive particles, etc., but if we go as early as possible, we know — to three significant figures, at least — that “13.8 billion years ago” is when the hot Big Bang began.

Objection #3: Okay, but the Universe didn’t really begin with the hot Big Bang; cosmic inflation preceded it. So why not start at the beginning of inflation?

Now you’re speaking my language. This one trips me up, too, because I know that going back 13.8 billion years to the hot Big Bang doesn’t quite take us back to the true beginning. Instead, it takes us back to an assumption that we used to think might be valid, but that we’re certain no longer is: that you could extrapolate our expanding-and-cooling Universe back, using the components of the Universe we have today, to a state where we had:

- arbitrarily hot temperatures,

- arbitrarily high densities,

- and where our 92-billion-light-year diameter Universe, today, was all contracted down into a single point.

This idea, that the start of the hot Big Bang corresponds to a singularity, was once taken as a given from perhaps the 1920s, when the Big Bang was first conceived, to the 1970s. But in the 1970s, we started to notice some peculiar properties that didn’t seem to align with the notion of extrapolating the hot Big Bang to those arbitrarily hot, dense, energetic, and small states.

For example, we saw that the Universe was spatially flat: where it was as though the expansion rate and the total amount of matter-and-energy in the Universe were perfectly balanced, down to the atom. That’s certainly possible within the Big Bang paradigm, but is in no way predicted. We also saw that the Universe had the same properties — including temperatures and densities — in regions that couldn’t have communicated or exchanged information with one another since the start of the hot Big Bang. And, for another, we didn’t see any leftover high-energy relics, like the kinds we might expect if the Universe ever did reach those ultra-hot states.

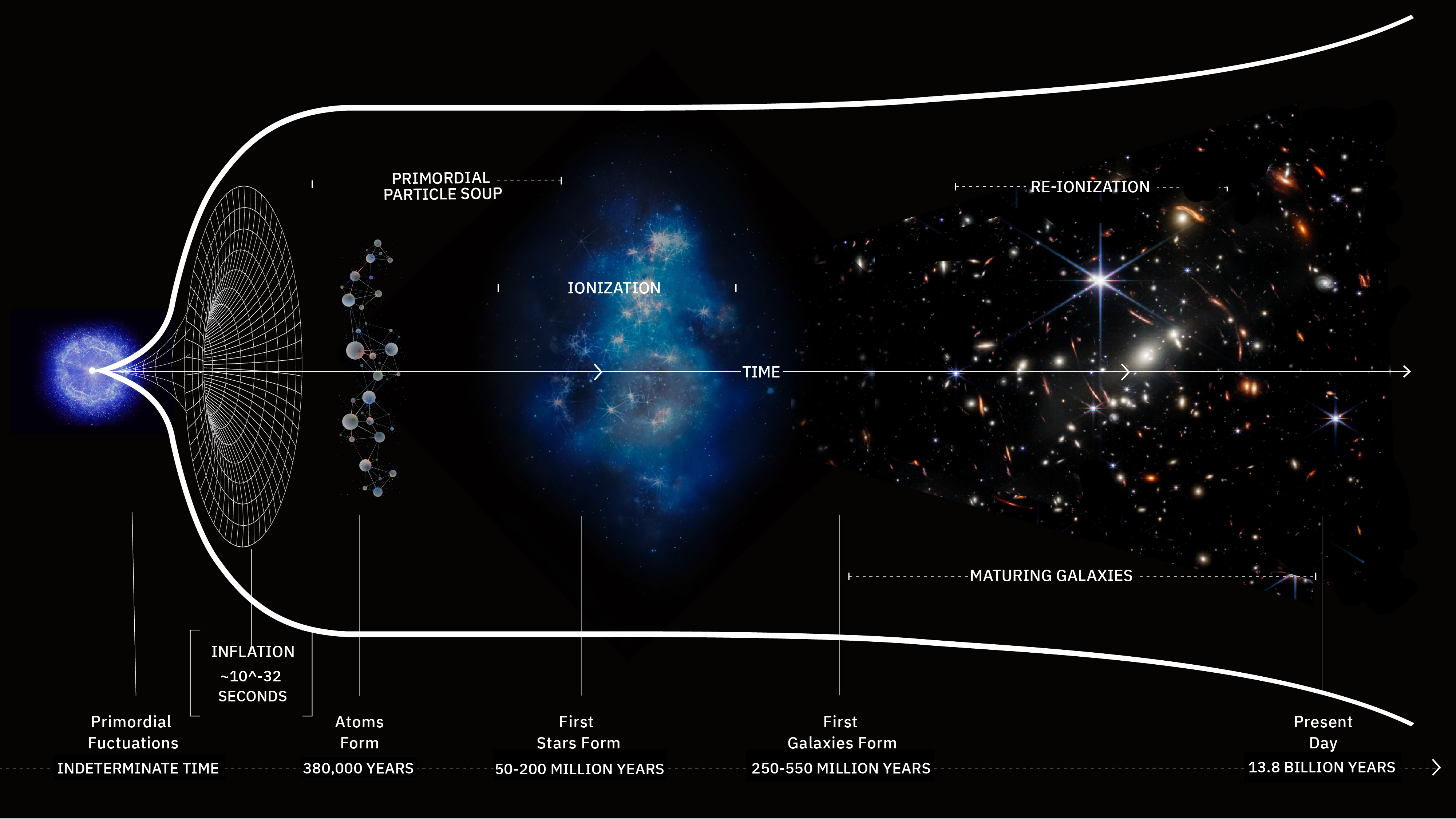

One possibility that emerged was that the Universe, before the hot Big Bang, was preceded by a period of exponential expansion that set up and gave rise to the conditions we observe. The Universe would be flat because inflation stretched it so it was indistinguishable from flat, irrespective of what it was before. It would be the same temperature in all directions because those now-disparate regions once overlapped, but inflation drove them apart. And there would be no high-energy relics because the Universe never achieved those arbitrarily high temperatures, but only reheated, after the end of inflation, to a finite temperature that was below the Planck scale.

What set inflation apart from other speculations, however, was its ability to make predictions that differed from the hot Big Bang’s if there were no inflation. Many of these predictions have been borne out by later observations, including:

- the prediction of an almost scale-invariant spectrum of density fluctuations, with a slight tilt to it,

- where all of the fluctuations would be adiabatic, and not isocurvature, in nature,

- including the existence of fluctuations on scales larger than the cosmic horizon set by the speed of light,

- and where the Universe reached a maximum temperature, as indicated by the CMB, that was well below the Planck scale.

All of these predictions have been subsequently confirmed, implying that there was a period of exponential expansion prior to the start of the hot Big Bang.

But how long did that period last, and what came before it?

For the first question of how long it lasted, that’s a question where we only have a lower limit, but there is no upper limit set by data. Inflation must have resulted in the Universe “doubling” in size at least a few hundred times, but if each “doubling” only takes something like 10-35 seconds, then that only tells us that the Universe must have undergone inflation for at least ~10-32 seconds. It could have lasted nanoseconds, seconds, years, trillions of years, googols of years, or even longer before ending and giving rise to the hot Big Bang.

But the answer is also, “It probably didn’t go on for an infinite amount of time,” when it comes to inflation. Although there may be loopholes that allow us to avoid an initial singularity, there are some very compelling theorems that strongly suggest that inflation arose from a pre-inflationary state that may have been singular. It’s unknown what the physical mechanism was that started it off, or if our presently understood laws of physics even apply to those early times.

But one thing is for certain: when we talk about the “age of the Universe,” we’re talking about the “age of the Universe that we can observe,” which includes the Universe going back to the start of the hot Big Bang and the tiny fraction-of-a-second over which the final moments of inflation left an imprint on our Universe. There was almost certainly more inflation before the final piece of it that left observable signals for us to see, and there was almost certainly something else before the onset of inflation, but how long they lasted, what they were like, and what caused them to begin are not questions that science has answered. The Universe we observe is 13.8 billion years old, but what came before it (and for how long) is still firmly in the realm of speculation.

Ethan is on medical leave until May 6th. Please enjoy a republication of this article from the Starts With A Bang archives!