Ask Ethan: Can we turn Einstein’s equations into Newton’s law?

- Back in 1915, Einstein put forth his most ambitious idea: the general theory of relativity, combining gravity with relativity to create an entirely new conception of our Universe.

- And yet, in most conventional circumstances, the predictions of Einstein’s theory are indistinguishable from that of its predecessor: Newton’s law of universal gravitation.

- Is it possible, then, to somehow reduce Einstein’s equations down to Newton’s equations? Or are they so fundamentally different that the task is utterly impossible?

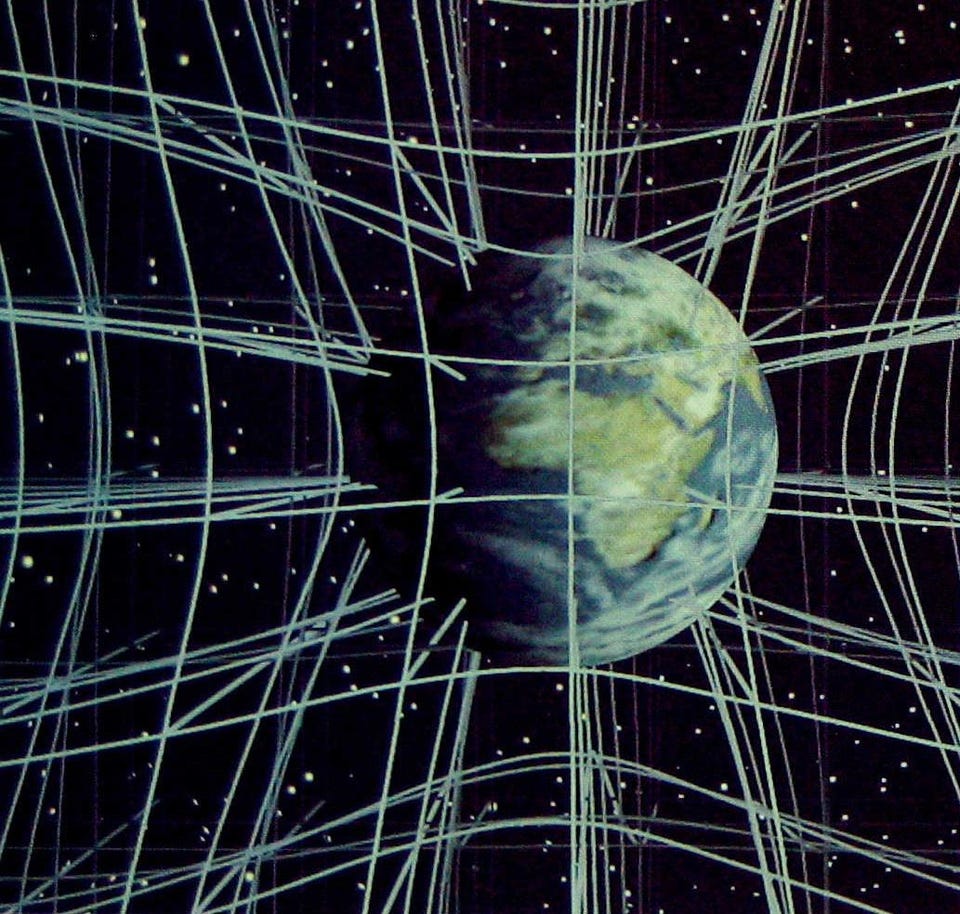

Although Einstein is a legendary figure in science for a large number of reasons — E = mc², the photoelectric effect, and the notion that the speed of light is a constant for everyone — his most enduring discovery is also the least understood: his theory of gravitation, general relativity. Before Einstein, we thought of gravitation in Newtonian terms: that everything in the universe that has a mass instantaneously attracts every other mass, dependent on the value of their masses, the gravitational constant, and the square of the distance between them. But Einstein’s conception was entirely different, based on the idea that space and time were unified into a fabric, spacetime, and that the curvature of spacetime told not only matter but also energy how to move within it.

Despite these conceptual differences, in nearly all practical cases, Einstein’s equations and Newton’s law of universal gravitation yield identical predictions. Does that imply that Einstein’s equations can somehow be collapsed, or reduced, down to Newton’s laws? It’s what James Raymond wants to know, asking:

“It seems like an amazing coincidence that Einstein’s equations give almost exactly the same result as Newton’s law of gravity. Popular lectures on gravity never seem to address this. I suspect it is not a coincidence. Is it possible to make a tiny change in Einstein’s equations to make them collapse to Newton’s law?”

It’s a great question, and one with a very nuanced answer. Yet, we can modify Einstein’s equations to recover Newton’s law. But no, it’s not a “tiny” change; it requires ignoring the most Einsteinian aspect of the theory of all: the principle of relativity itself. Here’s what it all means.

Newton’s law of universal gravitation is perhaps the best place to start: because it’s so apparently simple and straightforward. It simply says, as the equation above illustrates, that any two objects in the Universe, so long as they each have a mass (m1 and m2), and are separated by a certain distance (r), will attract one another (the negative sign) with a force that’s as strong as the gravitational constant (G) multiplied by both masses (m1 and m2) but divided by the distance squared (r²) separating both masses from one another. The nice thing about this is that it’s very easy to calculate: most high school students eventually learn how to do it with ease.

This force then causes those objects to accelerate, because the same force, F, that arises from gravitational attraction also appears in Newton’s other famous equation: F = ma, or equal to mass times acceleration. For most applications we can imagine, Newton’s laws work great. But that’s only because, in our everyday experience, we’re dealing with:

- distances that are relatively large,

- masses that are relatively small,

- and speeds that are negligibly little compared to the speed of light.

If you change any (or, worse, all) of these assumptions, then Newton’s equations no longer do a good job of describing the Universe. That’s when we need to move on to Einstein’s general relativity.

The fundamental idea of general relativity is this: that matter and energy tells spacetime how to curve, and that curved spacetime, in turn, tells matter and energy how to move. Although you might have heard this many times before, when Einstein first put it forth in 1915, it represented a revolutionary new view of the Universe. Four years after Einstein put his ideas forth, they were put to the test during a total solar eclipse: where the bending of starlight coming from light sources behind the eclipsed Sun agreed with Einstein’s predictions and not Newton’s. In the more than 100 years since, general relativity has passed every observational and experimental test we have ever concocted.

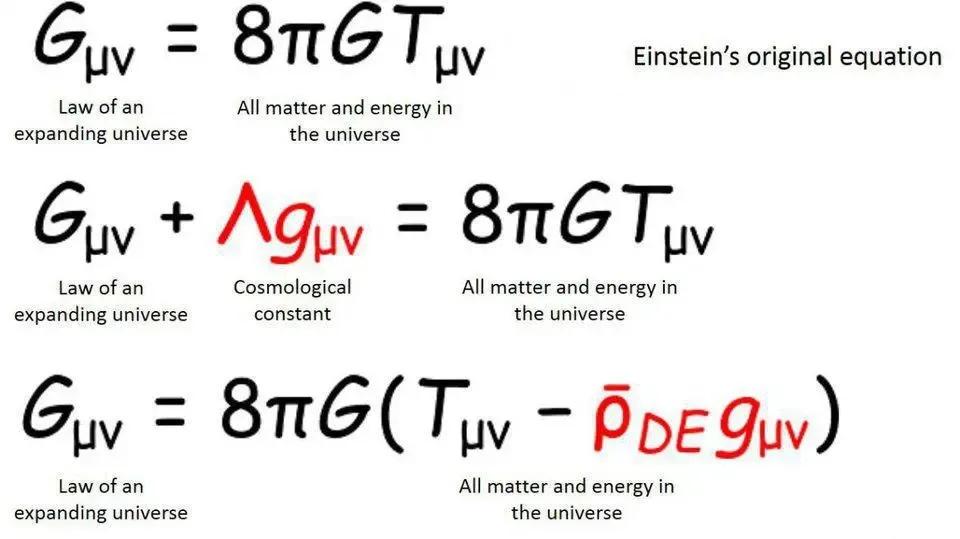

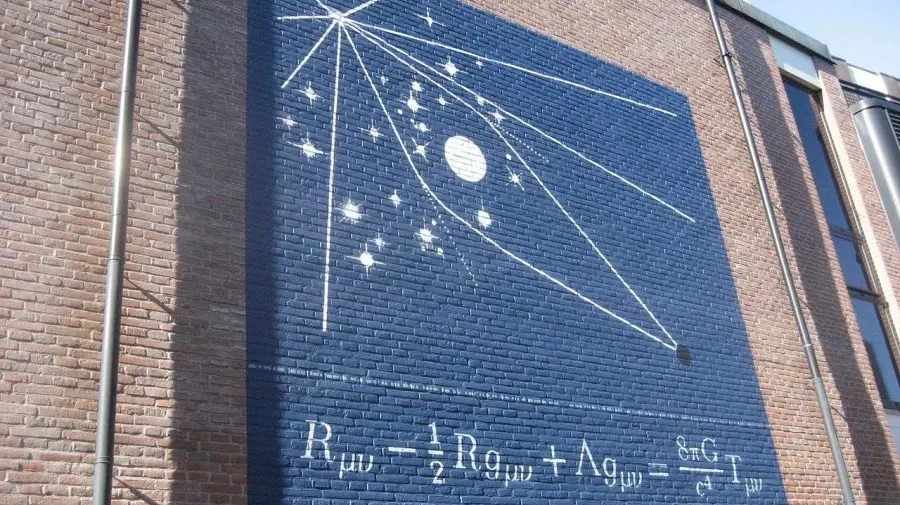

The Einstein equations, shown above, look pretty simple, in that there are only a few symbols present. But it’s quite complex.

- The first one, Gμν, is known as the Einstein tensor and represents the curvature of space.

- The second one, Λ, is the cosmological constant: an amount of energy, positive or negative, that is inherent to the fabric of space itself.

- The third term, gμν, is known as the metric, which mathematically encodes the properties of every point within spacetime.

- The fourth term, 8πG/c4, is just a product of constants and is known as Einstein’s gravitational constant, the counterpart of Newton’s gravitational constant (G) that most of us are more familiar with.

- The fifth term, Tμν, is known as the stress-energy tensor, and it describes the local (in the nearby vicinity) energy, momentum, and stress within that spacetime.

These five terms, all related to one another through what we call the Einstein field equations, are enough to relate the geometry of spacetime to all the matter and energy within it: the hallmark of general relativity.

You might be wondering what is with all those subscripts — those weird “μν” combinations of Greek letters you see at the bottom of the Einstein tensor, the metric, and the stress-energy tensor. Most often, when we write down an equation, we are writing down a scalar equation, that is, an equation that only represents a single equality, where the sum of everything on the left-hand side equals everything on the right. But we can also write down systems of equations and represent them with a single simple formulation that encodes these relationships.

E = mc² is a scalar equation because energy (E), mass (m), and the speed of light (c) all have only single, unique values. But Newton’s F = ma is not a single equation but rather three separate equations: Fx = max for the “x” direction, Fy = may for the “y” direction, and Fz = maz for the “z” direction. In general relativity, the fact that we have four dimensions (three space and one time) as well as two subscripts, which physicists know as indices, means that there is not one equation, nor even three or four. Instead, we have each of the four dimensions (t, x, y, z) affecting each of the other four (t, x, y, z), for a total of 4 × 4, or 16, equations.

Why would we need so many equations just to describe gravitation, whereas Newton only needed one?

Because geometry is a complicated beast, because we are working in four dimensions, and because what happens in one dimension, or even in one location, can propagate outward and affect every location in the universe, if only you allow enough time to pass. Our Universe, with three spatial dimensions and one time dimension, means the geometry of our Universe can be mathematically treated as a four-dimensional manifold.

In Riemannian geometry, where manifolds are not required to be straight and rigid but can be arbitrarily curved, you can break that curvature up into two parts: parts that distort the volume of an object and parts that distort the shape of an object. The “Ricci” part is volume distorting, and that plays a role in the Einstein tensor, as the Einstein tensor is made up of the Ricci tensor and the Ricci scalar, with some constants and the metric thrown in. The “Weyl” part is shape distorting, and, counterintuitively enough, plays no role in the Einstein field equations.

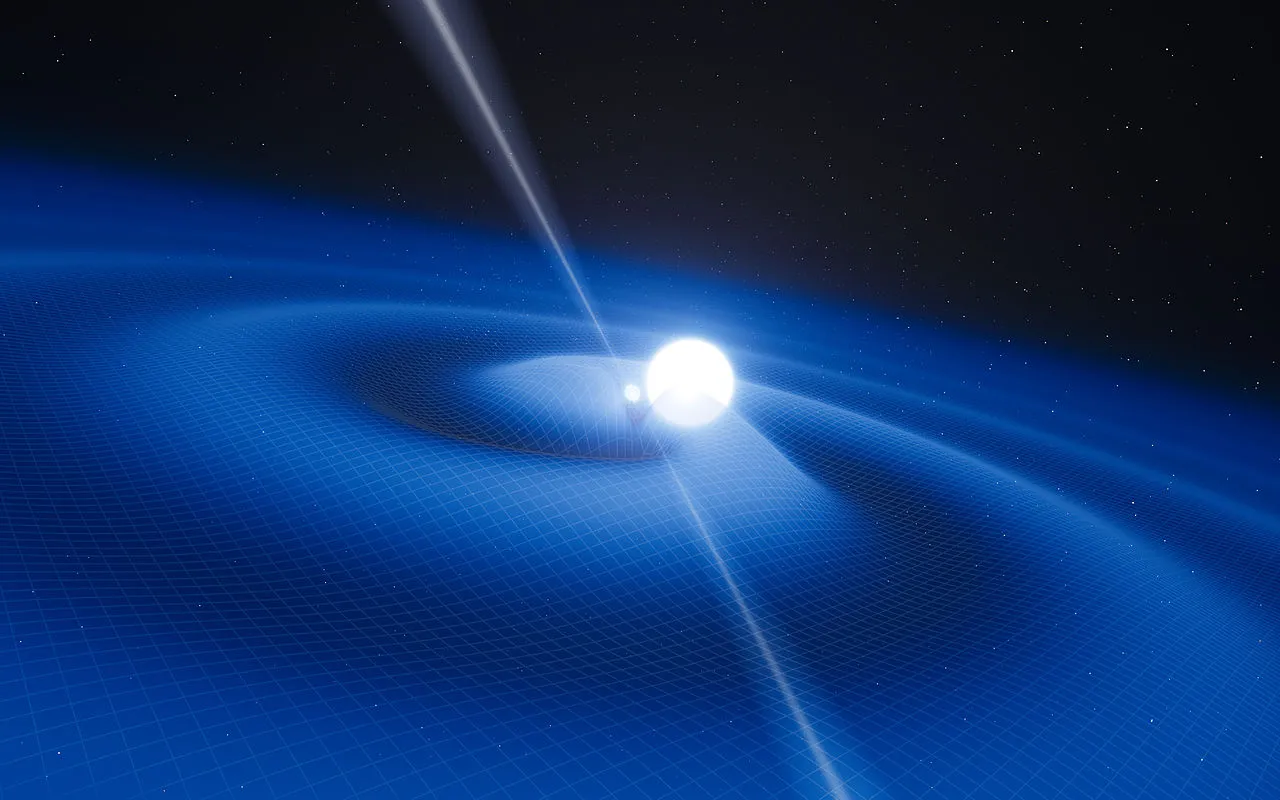

Credit: Tonia Klein/NANOGrav

The Einstein field equations are not just one equation, then, but rather a suite of 16 different equations: one for each of the “4 × 4” combinations. As one component or aspect of the universe changes, such as the spatial curvature at any point or in any direction, every other component as well may change in response. This framework, in many ways, takes the concept of a differential equation to the next level.

A differential equation is any equation where you can do the following:

- you can provide the initial conditions of your system, such as what is present, where, and when it is, and how it is moving,

- then you can plug those conditions into your differential equation,

- and the equation will tell you how those things evolve in time, moving forward to the next instant,

- where you can plug that information back into the differential equation, where it will then tell you what happens subsequently, in the next instant.

It is a tremendously powerful framework and is the very reason why Newton needed to invent calculus in order for things like motion and gravitation to become understandable scientific fields. In fact, F = ma is itself a differential equation, as if you give the initial positions, speeds, and masses of all the objects in a system at any moment in time, Newton’s laws can tell you what the positions and speeds of those objects will be at any point in the future.

Einstein’s differential equations are different, however. When we begin dealing with general relativity, it is not just one equation or even a series of independent equations that all propagate and evolve in their own dimension. Instead, because what happens in one direction or dimension affects all the others, we have 16 coupled, interdependent equations, and as objects move and accelerate through spacetime, the stress-energy changes and so does the spatial curvature.

However, these “16 equations” are not entirely unique! First off, the Einstein tensor is symmetric, which means that there is a relationship between every component that couples one direction to another. In particular, if your four coordinates for time and space are (t, x, y, z), then:

- the “tx” component will be equivalent to the “xt” component,

- the “ty” component will be equivalent to the “yt” component,

- the “tz” component will be equivalent to the “zt” component,

- the “yx” component will be equivalent to the “xy” component,

- the “zx” component will be equivalent to the “xz” component,

- and the “zy” component will be equivalent to the “yz” component.

All of a sudden, there aren’t 16 unique equations but only 10.

Additionally, there are four relationships that tie the curvature of these different dimensions together: the Bianchi identities. Of the 10 unique equations remaining, only six are independent, as these four relationships bring the total number of independent variables down further. The power of this part allows us the freedom to choose whatever coordinate system we like, which is literally the power of relativity: every observer, regardless of their position or motion, sees the same laws of physics, such as the same rules for general relativity.

Credit: NASA & ESA

There are other properties of this set of equations that are tremendously important. In particular, if you take the divergence of the stress-energy tensor, you always, always get zero, not just overall, but for each individual component. That means that you have four symmetries: no divergence in the time dimension or any of the space dimensions, and every time you have a symmetry in physics, you also have a conserved quantity.

In general relativity, those conserved quantities translate into energy (for the time dimension), as well as momentum in the x, y, and z directions (for the spatial dimensions). Just like that, at least locally in your nearby vicinity, both energy and momentum are conserved for individual systems. Even though it is impossible to define things like “global energy” overall in general relativity, for any local system within general relativity, both energy and momentum remain conserved at all times; it is a requirement of the theory.

Newton’s theory only conserves energy and momentum under those low-speed conditions that don’t occur very close to a large mass, however. You can only get Newton’s equations back from Einstein’s equations by ignoring 15 of the 16 components of Einstein’s tensor: only the first (tt) element, the “energy” element, can be non-zero, and that’s only a good approximation with small masses, large distances, and low speeds.

Another property of general relativity that is different from most other physical theories is that general relativity, as a theory, is nonlinear. If you have a solution to your theory, such as “what spacetime is like when I put a single, point mass down,” you would be tempted to make a statement like, “If I put two point masses down, then I can combine the solution for mass #1 and mass #2 and get another solution: the solution for both masses combined.”

That is true, but only if you have a linear theory. Newtonian gravity is a linear theory: the gravitational field is the gravitational field of every object added together and superimposed atop one another. Maxwell’s electromagnetism is similar: the electromagnetic field of two charges, two currents, or a charge and a current can all be calculated individually and added together to give the net electromagnetic field. This is even true in quantum mechanics, as the Schrödinger equation is linear (in the wavefunction), too.

But Einstein’s equations are nonlinear, which means you cannot do that. If you know the spacetime curvature for a single point mass, and then you put down a second point mass and ask, “How is spacetime curved now?” we cannot write down an exact solution. In fact, even today, more than 100 years after general relativity was first put forth, there are still only about ~20 exact solutions known in general relativity, and a spacetime with two point masses in it still is not one of them.

Originally, Einstein formulated general relativity with only the first and last terms in the equations, that is, with the Einstein tensor on one side and the stress-energy tensor (multiplied by the Einstein gravitational constant) on the other side. He only added in the cosmological constant, at least according to legend, because he could not stomach the consequences of a universe that was compelled to either expand or contract.

And yet, the cosmological constant itself would have been a revolutionary addition even if nature turned out not to have a non-zero one (in the form of today’s dark energy) for a simple but fascinating reason. A cosmological constant, mathematically, is literally the only “extra” thing you can add into general relativity without fundamentally changing the nature of the relationship between matter and energy and the curvature of spacetime.

The heart of general relativity, however, is not the cosmological constant, which is simply one particular type of “energy” you can add in but rather the other two more general terms. The Einstein tensor, Gμν, tells us what the curvature of space is, and it is related to the stress-energy tensor, Tμν, which tells us how the matter and energy within the universe is distributed.

In our universe, we almost always make approximations. If we:

- ignored 15 out of the 16 Einstein equations and simply kept the “energy” (tt) component,

- while making sure you only dealt with low speeds that were small compared to the speed of light,

- and large distance separations between objects,

- and also small masses relative to the distances in question,

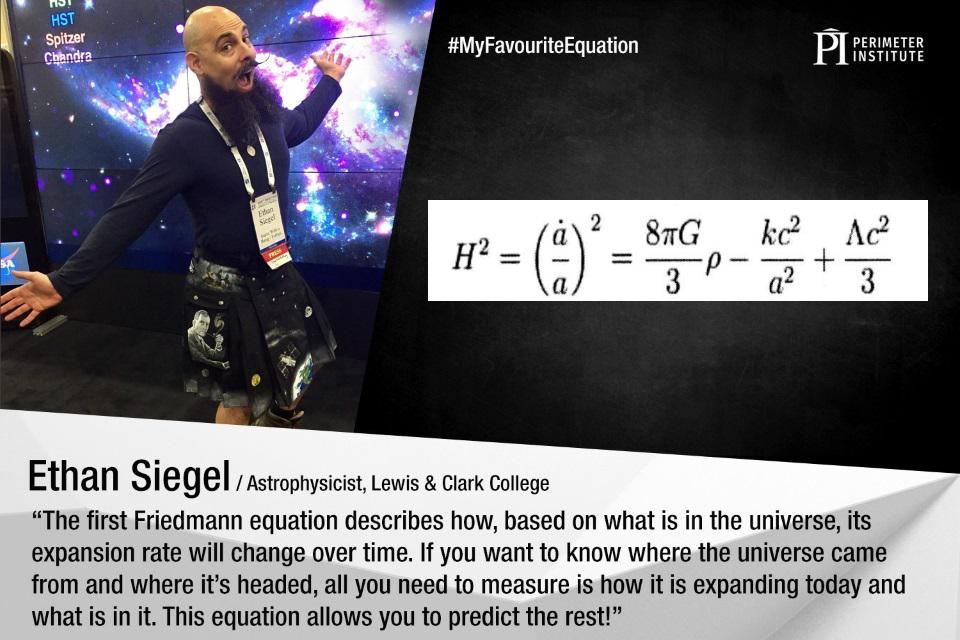

you would then recover the theory it superseded: Newton’s law of gravitation. If you instead made the Universe symmetric in all spatial dimensions and did not allow it to rotate, you’d get an isotropic and homogeneous universe, one governed by the Friedmann equations (and hence required to expand or contract). On the largest cosmic scales, this latter model actually seems to describe the Universe in which we live: not a Newtonian one.

But you are also allowed to put in any distribution of matter and energy, as well as any collection of fields and particles that you like, and if you can write it down, Einstein’s equations will relate the geometry of your spacetime to how the universe itself is curved to the stress-energy tensor, which is the distribution of energy, momentum, and stress. If there actually is a “theory of everything” that describes both gravity and the quantum Universe, the fundamental differences between these conceptions, including the fundamentally nonlinear nature of Einstein’s theory, will need to be addressed. Given their vastly dissimilar properties, the unification of gravity with the other quantum forces remains one of the most ambitious dreams in all of theoretical physics, but one divorce is certainly final: that of general relativity with Newtonian gravity. So long as it’s the curvature of spacetime that tells matter and energy how to move, and the distribution of matter and energy that determines the curvature of spacetime, Newton will forever be relegated to being an only sometimes-useful approximation.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!