Throwback Thursday: Where is Everybody?

If stars, planets, and biological processes are so common in the Universe, then where is everyone?

“If the Universe Is Teeming with Aliens… Where Is Everybody?”

–Stephen Webb

As egocentric as we are, we know that we are but one planet of many orbiting our Sun. Special, yes, because we’re the only one in our Solar System with advanced, thriving, intelligent life (for now), but still just one planet around one star. We look up in the heavens, every point of light we see is another chance — another opportunity — for planets, for life, and even for intelligence.

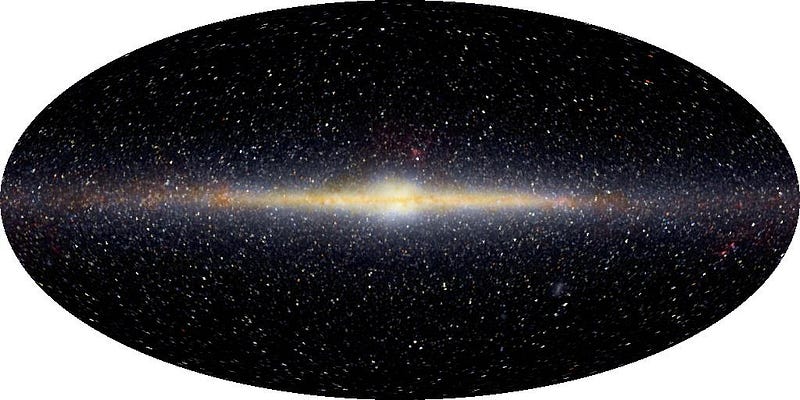

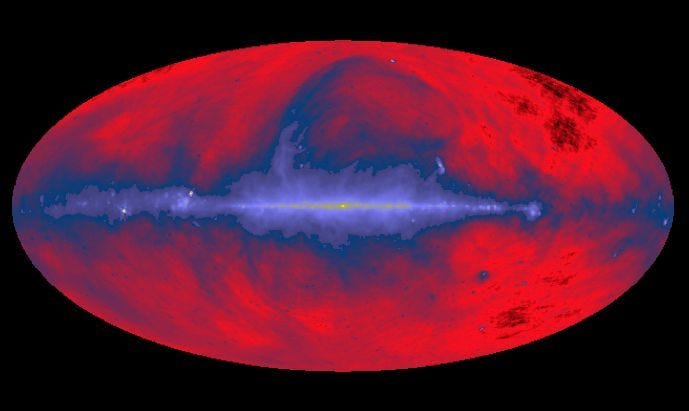

With hundreds of billions of stars (visible, above, in infrared wavelengths) in our galaxy alone, and literally trillions of planets around them, we have many, many chances for life to have evolved similarly to how it did here on Earth. With at least 200 billion galaxies in the Universe, it seems unfathomable to us that we would be alone as the only self-aware, intelligent, sentient lifeforms in the Universe.

And yet, the titular question of this article — where is everybody — is one of the most famous puzzles in modern science: Fermi’s Paradox. If the Universe is so conducive to life, and if there are so many opportunities for it within our galaxy alone, why isn’t there any evidence of extraterrestrial life?

Moreover, why haven’t we been visited by some extraterrestrial intelligence? After all, given the fact that our Universe is nearly 14 billion years old, while our galaxy itself is only a hundred-thousand light years from end-to-end, shouldn’t all of the potentially habitable planets have been visited, and colonized, by now?

The idea that this is, in fact, a paradox at all is predicated on a set of tacit assumptions that we made: that intelligent life — at least, as we understand it — is a relatively common occurrence in this Universe. If the chances are one-in-a-million that intelligent life arises on a planet, then surely there are millions of intelligent species in our galaxy alone. But what if the odds are much lower? Say, far less than one-in-a-trillion?

Then we’d be lucky if there were other intelligent lifeforms out there in the Universe at all, and it’d be incredibly unlikely to find another one in our isolated galaxy.

So that begs the question: Is there really anything paradoxical about the fact that — to the best of our knowledge — we’re thus far alone in the Universe?

Let’s take a look.

This is Earth, our home. So far, it’s the only place we know of that either harbors or has ever harbored life in the Universe, much less intelligent, sentient, self-aware and (possibly) capable-of-communicating-with-alien life. (Although the possibilities for this changing in the near future are tantalizing.)

We assume that if there are intelligent extra-terrestrials out there, they’ll be made of the same chemical elements we are. Not because it’s the only way for the Universe to store complex information, or because we think any other methods are prohibitive, but because this is something we understand. In science, we tend to be conservative and rely on the fact that we know at least one way that intelligent life can arise.

And if it works this way here, for us, perhaps it worked in a similar fashion elsewhere, too, for someone else. Other than the right elements (which are all over the galaxy and Universe by this point), what we need is actually pretty simple.

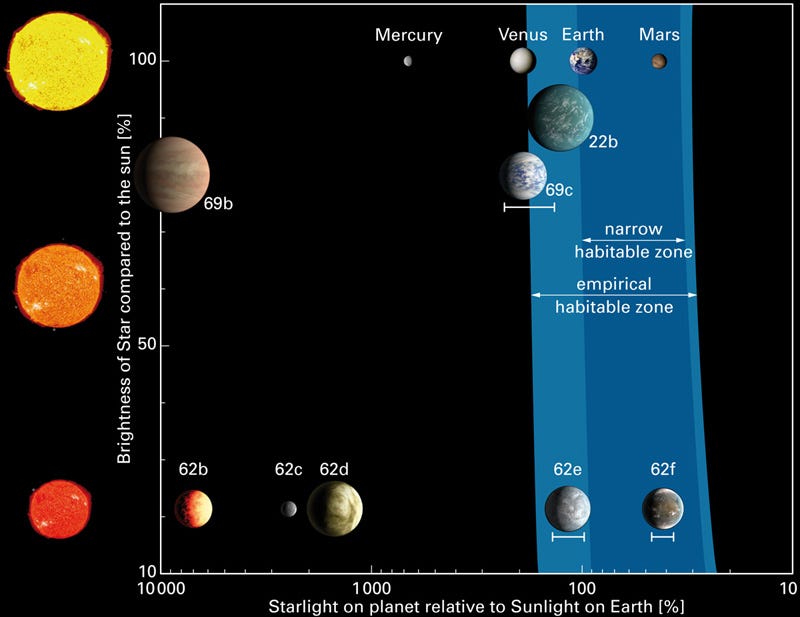

We need to be the right distance from the Sun in order to have liquid water. In other words, we need the temperature to be a particular value, and for that value to be relatively constant. If it were too cold, everything would freeze, and if too hot, everything would both boil and too many chemicals would spontaneously denature for complex life to sustain itself.

Fortunately, we’re not speculating about this like Frank Drake had to when he thought about this (and put forth his now-famous equation) fifty years ago. We know of thousands of planets that orbit around other stars now!

As best as we can tell — extrapolating what we’ve discovered to what we haven’t yet looked at or been able to see — there ought to be around one-to-ten trillion planets in our galaxy that orbit stars, and somewhere around forty to eighty billion of them are candidates for having all three of the following properties:

- being rocky planets,

- located where they’ll consistently have Earth-like temperatures,

- and that ought to support and sustain liquid water on their surfaces!

So the worlds are there, around stars, in the right places! In addition to that, we need them to have the right ingredients to bring about complex life. What about those building blocks; how likely are they to be there?

Believe it or not, these heavy elements — assembled into complex molecules — are unavoidable by this point in the Universe. Enough stars have lived and died that all the elements of the periodic table exist in fairly high abundances all throughout the galaxy.

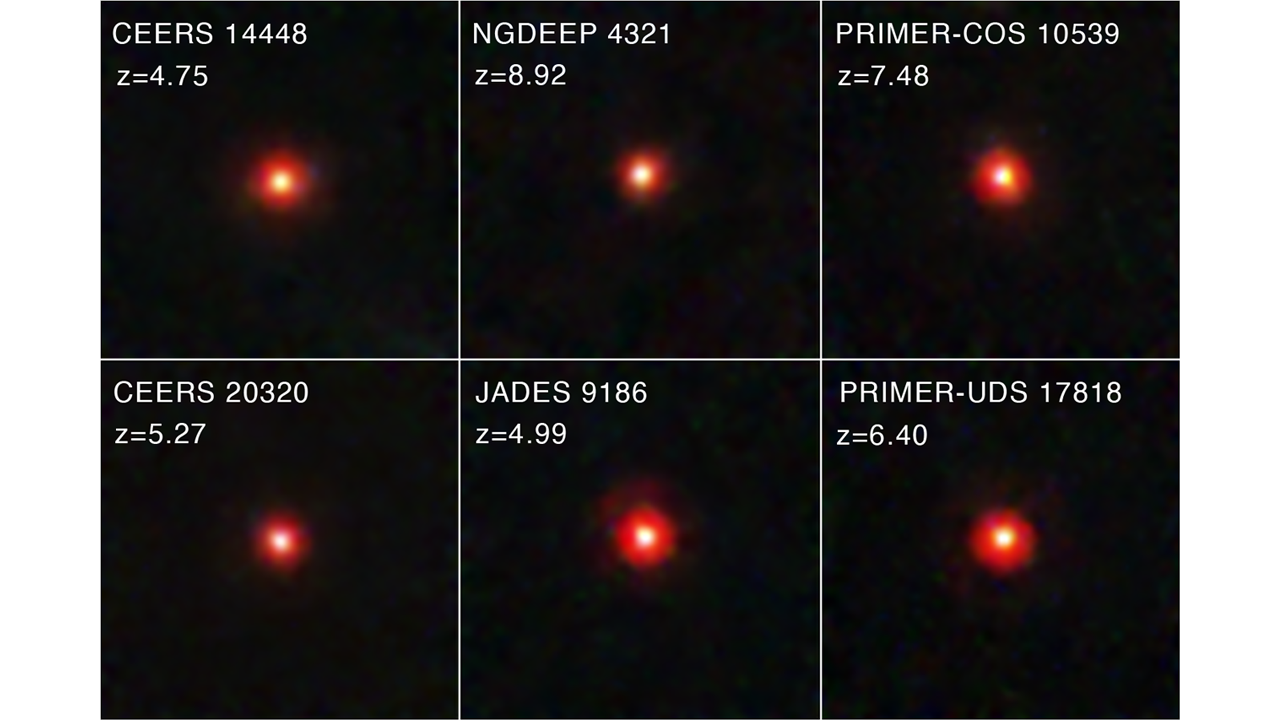

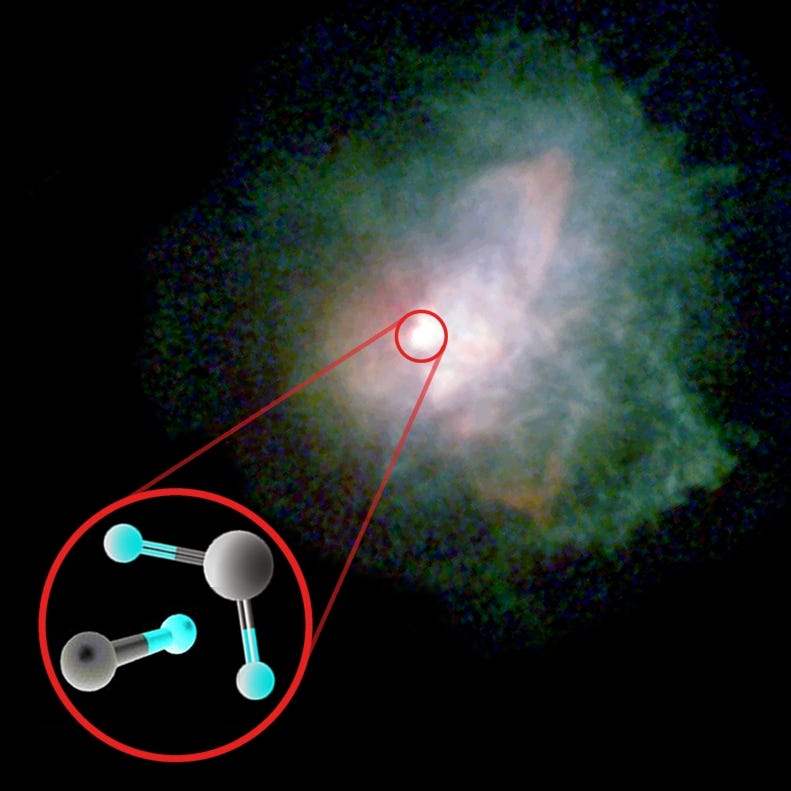

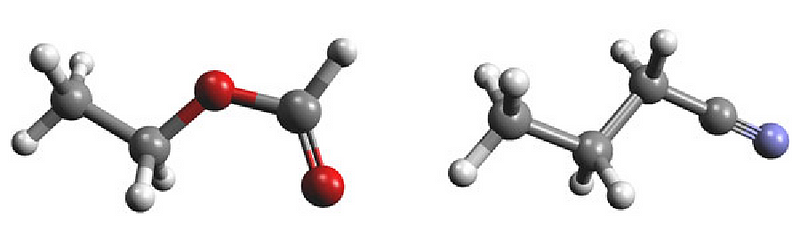

But are they assembled correctly? Taking a look towards the heart of our own galaxy is molecular cloud Sagittarius B, shown at the top of this page. In addition to water, sugars, benzene rings and other organic molecules that just “exist” in interstellar space, we find surprisingly complex ones.

Like ethyl formate (left) and n-propyl cyanide (right), the former of which is responsible for the smell of raspberries! Molecules just as complex as these are literally in every molecular cloud, protoplanetary disk and stellar outflow that we’ve measured. So with tens of billions of chances in our galaxy alone, and the building blocks already in place, you might think — as Fermi did — that the odds of intelligent life arising many times in our own galaxy is inevitable.

But there is a big difference between an organic molecule and an intelligent lifeform. On Earth alone — the one place where we know it worked — it took over four billion years and a slew of unlikely events to bring us about.

What was it that needed to happen, and what are the odds of it happening? Let’s go through it, both liberally and conservatively, and see what we get.

First, we need to make life from non-life. This is no small feat, and is one of the greatest puzzles around for natural scientists in all disciplines: the problem of abiogenesis. At some point, this happened for us, whether it happened in space, in the oceans, or in the atmosphere, ithappened, as evidenced by our very planet, and its distinctive diversity of life.

But thus far, we’ve been unable to create life from non-life in the lab. So it’s not yet possible to say how likely it is, although we’ve taken some amazing steps in recent decades. It could be something that happens on as many as 10-25% of the possible worlds, which means up to 20 billion planets in our galaxy could have life on them. (Including — past or present — others in our own Solar System, like Mars, Europa, Titan or Enceladus.) That’s our optimistic estimate.

But it could be far fewer than that as well. Was life on Earth likely? In other words, if we performed the chemistry experiment of forming our Solar System over and over again, would it take hundreds, thousands, or even millions of chances to get life out once? Conservatively, let’s say it’s only one-in-a-million, which still means, given the pessimistic end of 40 billion planets with the right temperature, there are still at least 40,000 planets out there in our galaxy alone with life on them.

It seems hard to fathom — given this — that there isn’t a wild diversity of intricate life out there in the Universe, having had billions of years to evolve into creatures that would no doubt put our imaginations to shame. Once life gets “under the skin” of a planet, so to speak, it’s hard to imagine an event short of a planetary ejection, a stellar collision, or the end-of-life of the parent star ending all life on that world. We’ve had many catastrophes occur in the history of the Earth, but not only did life survive, the newly opened ecological niches only seemed to accelerate the evolution of more complex, differentiated creatures.

But we want something even more than that; we’re looking for large, specialized, multicellular, tool-using creatures. So while, by many measures, there are plenty of intelligent animals, we are interested in a very particular type of intelligence. Specifically, a type of intelligence that can communicate with us, despite the vast distances between the stars!

So how common is that? From the first, self-replicating organic molecule to something as specialized and differentiated as a human being, we know we need billions of years of (roughly) constant temperatures, the right evolutionary steps, and a whole lot of luck. What are the odds that such a thing would have happened? One-in-a-hundred? Well, optimistically, maybe. That might be how many of these planets stay at constant temperatures, avoid 100% extinction catastrophes, evolve multicellularity, gender, become differentiated and encephalized enough to eventually learn to use tools.

But it could be far fewer; we are not an inevitable consequence of evolution so much as a happy accident of it. Even one-in-a-million seems like it might be too optimistic for the odds of human-like animals evolving on an Earth-like world with the right ingredients for life; I could easily imagine that it would take a billion Earths (or more) to get something like human beings out just once. Because at the end of the day, here’s what we need to do.

We need for the alien species to broadcast a signal of sufficient magnitude in a particular manner that it can be detectable above the cosmic background of the Universe. That could be in the radio — which would require an amazing array of radio telescopes to detect — or it could be in another wavelength of light or by another method entirely. We need a little bit of luck in that both civilizations — the one sending the signals and the one receiving it — need to conceive of the same method to find one another.

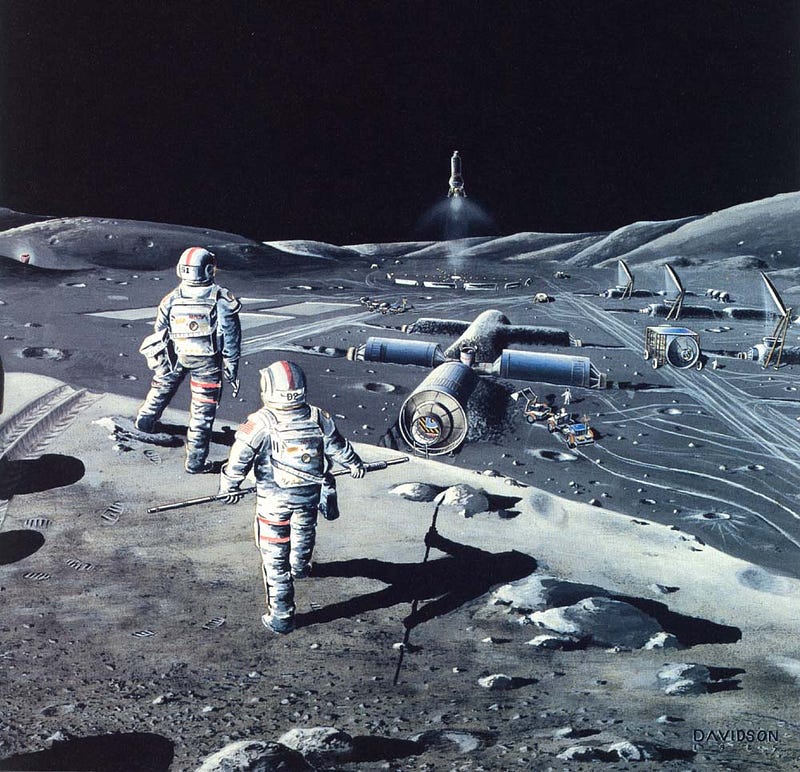

Unless, of course, one of them masters interstellar travel, and simply makes the journey to say “hello” to the other.

If we take the optimistic estimate of the optimistic estimate above, perhaps 200 million worlds are out there capable of communicating with us, in our galaxy alone. But if we take the pessimistic estimate about both life arising and the odds of it achieving intelligence, there’s only a one-in-25,000 chance that our galaxy would have even one such civilization.

And we’re not done yet.

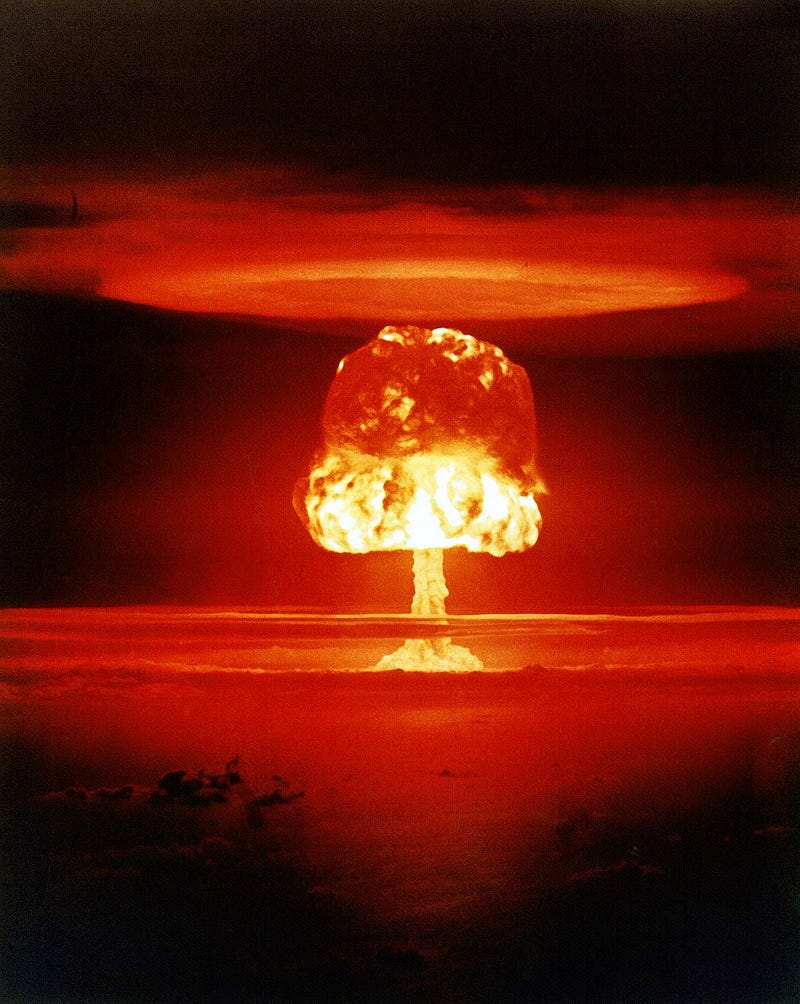

Because human haven’t been around forever, and we won’t be around forever. And for that matter, neither will humanity’s equivalent on another world.

Whether it’s nuclear war, natural disasters, or a slow poisoning of our own environment, at some point there won’t be humans on Earth any longer. For what percent of our star’s lifetime will humans be around? Or, of all the civilizations that may have existed over the history of the Universe, what are the chances that there are aliens out there now, capable of communicating with us?

Our Universe has been around for some 13.8 billion years, and we’ve only had this capability — to search the galaxy for other extraterrestrials, to transmit our own signals, and to begin to leave the Earth — for less than a hundred of them. Human beings (in our current evolutionary form) have only been around for a little over a hundred thousand years, or about 0.001% of the history of the Universe. Optimistically, perhaps we will thrive for millions of years before we either evolve into something completely different or destroy ourselves. But, pessimistically, we may only be around — in our able-to-communicate-phase — for a few hundred years from the time we first began to truly search for life.

Taking the millions-of-years estimate and our prior optimistic figure, that means there may be as many as 20,000 civilizations ready to communicate with us right now in the Milky Way galaxy.

But taking the pessimistic number and applying our pessimistic estimate of life arising and human-like intelligence evolving? There’s only about a 10% chance of there being one Earth-like world, today, with a species like us on it, in all the galaxies in the entire Universe.

Regardless of whether the optimists or the pessimists are closer to being right, there is no paradox. If the pessimists are even close to right, it’s because there isn’t anybody out there for us to talk to. And if the most optimistic of the optimists are right, there’s still almost nobody out there for us to talk to! Even if there are tens of thousands of civilizations in our galaxy, right now, that still means that the nearest one is likely to be many hundreds (if not thousands) of light-years away.

But, despite the long odds, we have to look.

There’s too much to know, too much to gain, and too much to learn for us to not ask these questions. Any civilization that talks to us will likely have been around — as you can tell from the estimates — in a technologically more advanced state than us for thousands or years, if not hundreds of thousands (or more). When you think of all the social and political problems that we’ve solved (and are solving now) just over the past few hundred years, and the hurdles we have coming up over the next few hundred (including population, pollution, energy, resource management, human rights, and more), you must immediately realize that any civilization that talks to us has likely already solved those problems.

So where is everybody? If they exist at all, they’re very far away.

But even if we side with the most pessimistic estimates, we still expect that life, in some form or another, is sure to be close by. We wouldn’t be doing justice to the curious, investigative nature of humanity — the very nature that’s led us this far — if we stopped looking now. After all, as Carl Sagan so beautifully said,

I guess I’d say if it is just us…

seems like an awful waste of space.

If the answer turns out to be that there isn’t anyone else, perhaps it’s up to humanity to change that, and seed life on other worlds. And if there is somebody else, well, I want to know! Don’t you?

Head on over to our comment forum at Scienceblogs and weigh in with your opinion, comments, questions and thoughts!