Throwback Thursday: Are asteroids dangerous?

Sure, they wiped out the dinosaurs, but do they really pose a risk to humans?

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” –H. P. Lovecraft

Human beings haven’t been around on Earth forever. In the grand scheme of things, we haven’t been around very long at all. Consider that animals like the duck-billed platypus and the koala have been in pretty much their current form for 50 million years — turtles and tortoises for ~200 million years — while humans have been around a few hundred thousand at most. Chances are, we’re not going to be around forever, either. It’s only a question of how and when we’re going to go out.

When you think about the question of how, we’re all aware that one of the ways that human life on Earth could end, conceivably, is the same way that the dinosaurs went down. A large enough asteroid striking Earth at a typically colossal speed — tens to hundreds of miles/kilometers per second — could catastrophically cause a mass extinction unseen on Earth in the past 65 million years. It’s an unsettling thought: that if a large enough space rock were randomly hurled in our direction, all life as we know it on our planet would be dramatically altered. And more importantly, for us, the entire human race would very likely be one of its casualties.

Even barring a disaster of species-killing proportions, large asteroid strikes are common enough that an ill-placed strike could be disastrous to a large portion of humanity. Take Barringer Crater (also known as Meteor Crater), for example. Formed just 50,000 years ago by the impact of a “city-killer” sized asteroid, it left a crater 1,200 meters (3,900 feet) in diameter. If comparable asteroid strike occurred over a densely populated area like New York City, London or Tokyo, millions of people could be killed, and at least hundreds of billions of dollars worth of damage would easily be done.

Considering the lack of an early warning system, and the difficulty of identifying all but the largest asteroids in advance (and even the larger ones, when they happen to come from the direction of the Sun), it’s not difficult to imagine almost the entire population of a metropolis wiped out in a single unfortunate stroke of bad luck.

This isn’t a never-gonna-happen even, either. You’re all very familiar with, quite recently, some major events that have occurred to remind us how devastating the Universe can be.

In 1908, a huge fireball descended over Russia, followed by a midair explosion. The heat and impact could be felt from up to 40 miles (65 kilometers) away, as people felt like their bodies were on fire and wereliterally knocked over. Nineteen years later, the site of the Tunguska Event was discovered, and for about 40 kilometers in all directions, the terrain was completely leveled.

About 80 million full-grown trees had been knocked over by an explosion estimated to have released the equivalent of 10 million tonnes of TNT exploding, or about 40% as much energy as the largest nuclear bomb ever detonated on Earth.

What’s truly frightening about this event is that it very likely occurred due to an asteroid that was a mere 100 meters (or 330 feet) in diameter, weighing “only” around 100,000 tonnes. This was probably about the same size — give or take a factor of two or three — as the asteroid that created Meteor Crater. But you’re probably far more familiar with an even more recent event.

Just two years ago, a 15 meter wide asteroid — of the type that we never saw coming — hit Earth’s atmosphere over Chelyabinsk, Russia, injuring over 1,000 people and causing significant property damage. Although this was maybe only 5% as powerful as the Tunguska event, it’s much more frightening because:

- it happened near a populated area,

- it’s a reminder of how random and frequent these events are,

- and if this had just happened to be a significantly larger asteroid, it could’ve wiped out all of Chelyabinsk, a city of over a million people!

Now, the idea that you could be killed by a space rock — or that all of humanity could be wiped out due to one — is no doubt terrifying. But humans are notoriously bad at estimating the risk due to infrequent but catastrophic events, and the only cure for that is quantitative science.

First off, I want you to think about all the humans that have ever lived for all the time that records have been kept. I want you to think about all the asteroids that have ever struck Earth in that time, and ask yourself about the odds of a human being struck by one. How many times, would you think, a human being has been hit by an asteroid here on Earth?

Have you made your guess?

The answer is one, and this is her: Ann Hodges of Alabama, struck by a meteor in 1954. So what’s with all the fear? Like I said earlier, there’s one type of risk-assessment that humans are really, really bad at: estimating the quantitative risk of a low-probability, high-consequence event. It’s the same reasoning behind why we sink so much money into the lottery, despite the odds, and it’s why it’s so easy for us to fall victim to fear-mongering around the issue of asteroid strikes. In fact, earlier today, cosmonaut and first human to walk in space, Alexey Leonov, said that asteroids are the greatest threat to humankind.

There’s good science behind asteroid tracking and risks, but it’s often very, very poorly presented to the world, and we all suffer as a result.

You see, the B612 Foundation has done some remarkable work tracking recent asteroid impacts on our planet, and has found that 26 asteroids have struck Earth since the year 2000. The “fear factor” here is that we didn’t see a single one coming, and were completely caught by surprise by each and every one.

It’s a well-known fact that city-killer asteroids, like the one that caused the Tunguska event or Meteor Crater, strike Earth anywhere between once every couple of millennia to possibly as frequently as once a century. In addition, even though we’ve discovered tens of thousands of asteroids, we’ve only observed an estimated 1% of the potentially severely damaging ones out there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66mHHaWtlt0

But how high is the risk, actually? Consider this analysis:

- With tens-of-thousands of city-killer-and-larger asteroids discovered,

- Even if that’s 1% of the total out there, meaning there are millions,

- Even if we assume that they all wind up hitting Earth eventually, and

- Even if the rate of city-killers hitting Earth is the most pessimistic estimate of once-per-century,

- That means there will be no asteroids left in the Solar System, because they all will have struck Earth, in another few hundred million years.

Think someone’s overestimated something there? Yeah, me too. Let’s take a look with the flaws in our fear-based reasoning.

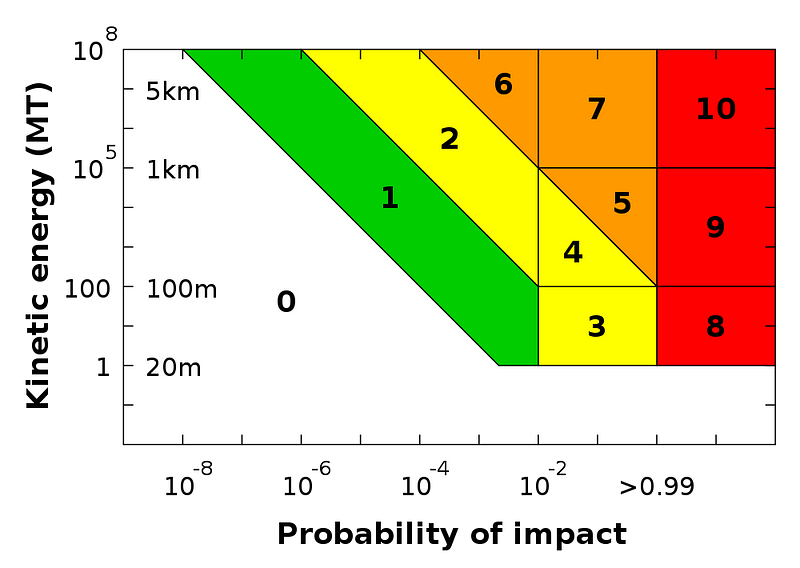

First off, anything as small as any of these 26 asteroid strikes observed since 2000 rates a zero on the Torino Scale: the scale we’ve devised for measuring the threat of an asteroid to humans. Fortunately for all of us, we have a wonderful defense shield against the small, frequent asteroids that interact with our world: the atmosphere!

An asteroid smaller than about 10 meters (33 feet) that hits the atmosphere will not make it down to the Earth’s surface, nor will it affect anything that happens on the ground in any meaningful or destructive way.

All you get is a brilliant flash of light, known colloquially as a shooting star for tiny ones, or as a bolide (to astronomers, with apologies to geologists) for the larger ones!

Second off, the actual rate of city-killers striking Earth appears to be much less frequent than once-a-century, and that the vast majority of city-killers that do strike Earth occur either over the ocean (and away from heavily populated coastal regions, where they could cause a devastating tsunami) or over extremely sparsely populated regions. It’s estimated that even if a city-killer struck the Earth in a random location, it would have approximately an 80% chance of killing no one. Remember that 70% of the Earth’s surface is water, and the greatest land areas on Earth — by country — are taken up by Russia and Canada, which are largely unpopulated over most of their land mass.

And finally, it is true that the more massive the asteroid gets, the more catastrophic its damage is going to be. Taking the entire Solar System into account, and modeling asteroid strikes as occuring completely randomly (including ones that would end all life on the planet), you can estimate your odds of dying from an asteroid strike in any given year.

Want to know what those odds are? One-in-70,000,000. On average.

Now you know me: I’m a huge fan of astronomy, astrophysics and space exploration. I absolutely believe that we should be building optical and infrared telescopes to learn more about our Solar System and the asteroids in it, as well as the Universe beyond it.

But I think “fear of getting wiped out” or “fear of a catastrophic asteroid strike” are terrible reasons for doing so. And — I want to be clear here — the reason I think it’s terrible to act out of fear is not some sort of machismo; it’s because this is quantitatively something that’s very unlikely to negatively affect humanity in any appreciable way.

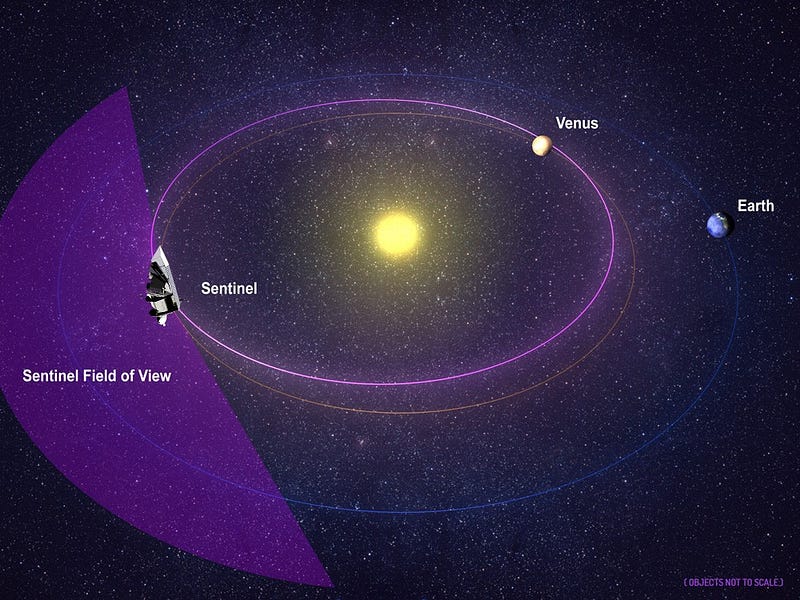

It’s possible that we’ve slightly underestimated our risks, and I think it’s a good idea to fly the asteroid-finding Sentinel Mission that the B612 Foundation is planning. But we shouldn’t be flying it out of fear; the last thing we need is for people to be unfoundedly afraid of the Universe! (You have a much greater risk of dying from a lightning strike, plane crash, earthquake, dog bite or accidental fireworks discharge than you have of dying from an asteroid strike.)

What’s the breakdown of the one-in-70,000,000 chances of us dying? Let’s dive into the numbers.

Odds that are heavily weighted like this are among the most difficult for humans to intuit. We get a planet-killer asteroid — the kind that wiped out the dinosaurs — once every few hundred million years; the largest events are the most destructive but also the most unlikely. Your “one-in-70,000,000” chances of death factor these catastrophes in very heavily. If we get hit by the Earth-killer this year, all 7 billion of us go down, game over.

But what if we don’t?

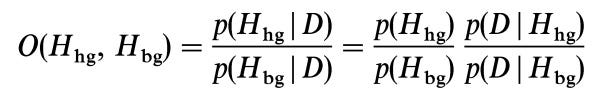

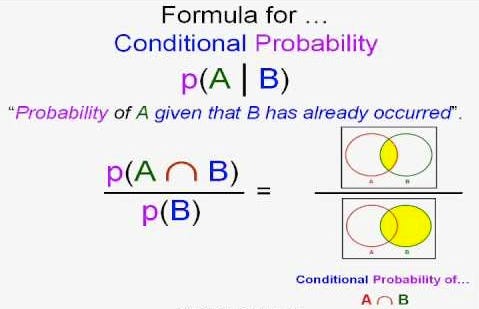

You might instead want to look at conditional probability: what are your chances of dying if the Earth-killer doesn’t hit this year? It’s much lower: somewhere around half those odds. City-killers are much more frequent, but much less destructive. They might take out a million people once every ten-to-hundred thousand years (when we get unlucky with their location), but much fewer during most strikes, which probably occur only every few hundred years. There are asteroids in-between city-killers and planet-killers, but those probably hit once every hundred thousand-to-a million years as well. So on average there are probably 100 people (assuming our world’s population remains level at 7 billion indefinitely into the future) who’ll die every year from asteroid strikes, but that’s going to be heavily skewed towards years where there’s a city-killer or larger asteroid hitting the Earth.

Most years, no one dies of asteroid strikes, and in the years where someone does die, it’s going to be far fewer than 100 people who do. But when the wrong year comes along, lots more than 100 people will die, and over long enough timescales, that will average out to about 0.0000014% of the world’s population dying of an asteroid strike every year.

So provided that there’s no killer asteroid coming, and there’s no reason to believe that there’s a city-killer coming our way in the next year, decade or our lifetime, there is a risk, but the risk is small and quantified. Even if it does happen, the odds that it will cause tremendous amounts of death or damage is small as well. Realistically, the odds are tiny that any asteroid strike will happen to humanity in our lifetimes, our children’s lifetimes, or their children’s children’s children’s lifetimes. Each year that passes sees roughly a 0.0000005% chance of a species-threatening asteroid coming our way, while real threats — environmental, medical and political (i.e., war) — could literally wipe us off the face of the Earth in the blink of an eye.

So don’t fear the asteroids! The reason to do this type of science is for knowledge, not for fear. I know that many of you think that so long as we invest in science, the reason doesn’t matter, but I give our world more credit than that. If we want to build a world that values and appreciates science, we have to be honest about what it is, what it does, and what the scientific enterprise is all about.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs.