The Pale Blue Dot Celebrates Its 29th Anniversary, Reminding Us How Small And Fragile We Are

From billions of miles away, a faint, single pixel shows us how precious and alone Earth truly is.

There are people alive today who can remember a time where no human-made creation had ever crossed the line from Earth’s atmosphere into space. Even today, it’s incredibly costly to launch a device into space, and it requires even more power than that to escape from the gravitational pull of our planet entirely. As the space race unfolded, humanity left the bonds of Earth’s orbit, walked on the surface of the Moon, and sent space probes to every other planet in our Solar System.

A couple of those spacecraft sent to the farthest reaches of space have now exited our Solar System: Voyager 1 and 2. On their way out, however, powered by their fading nuclear power sources, one of them took a look back at the planet that spawned its existence. On February 14, 1990, Voyager 1 captured this photo of Earth: the Pale Blue Dot. Our view of our home world has never been the same since.

In August and September of 1977, the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes were launched, with the purpose of studying the worlds of the outer Solar System. Voyager 2 was actually launched first: 16 days before its twin. While Voyager 2 wound up taking a grand tour of the Solar System, flying past the Uranian and Neptunian systems and photographing their atmospheres, moons, and rings up close, Voyager 1 took a vastly different path.

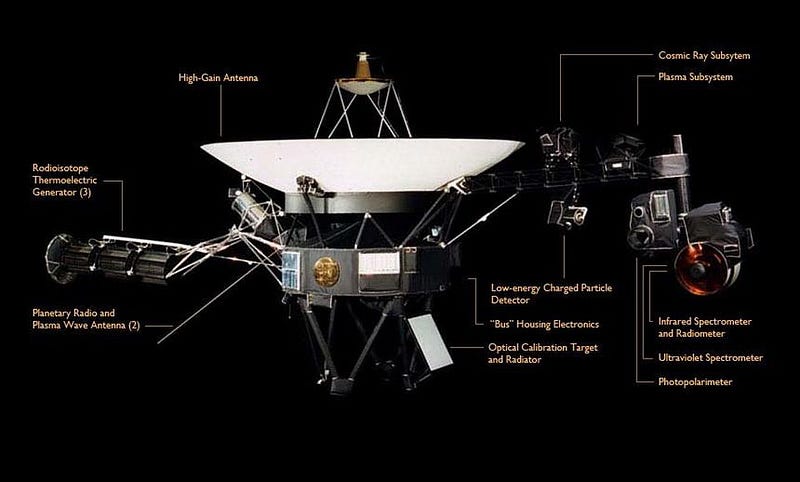

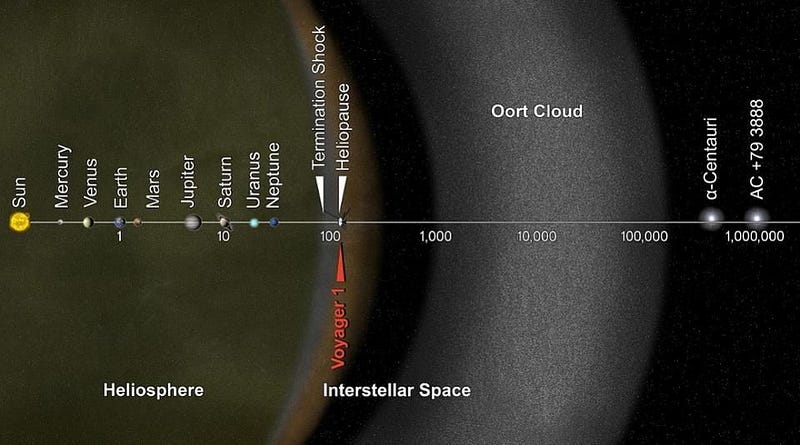

Its main objectives were to visit Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. After Voyager 1 studied the properties of these worlds, including their weather, magnetic fields, rings and satellites, it used the gravitational slingshot technique to achieve escape velocity from the Solar System. It is presently the most distant human-created object from Earth, at a distance of over 145 astronomical units: more than 3 times the distance from the Sun to Pluto.

Voyager 1 completed its main mission in 1980, and an extended mission was selected and enacted. Rather than remain in the plane of the Solar System, where the planets lie, it was decided to be thrust on a different trajectory: towards the constellation Ophiuchus and out of the Solar System. Owing to its final gravity assist, it was set up to become the most distant human-made object from Earth, a record which it achieved in 1998 and has held ever since.

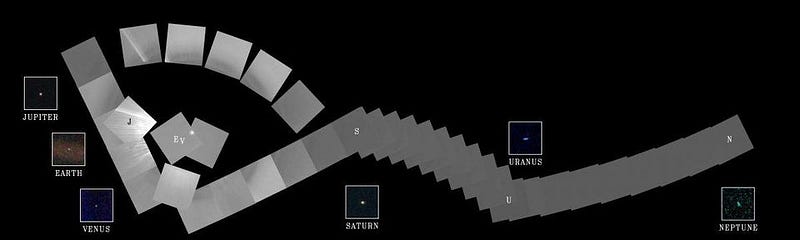

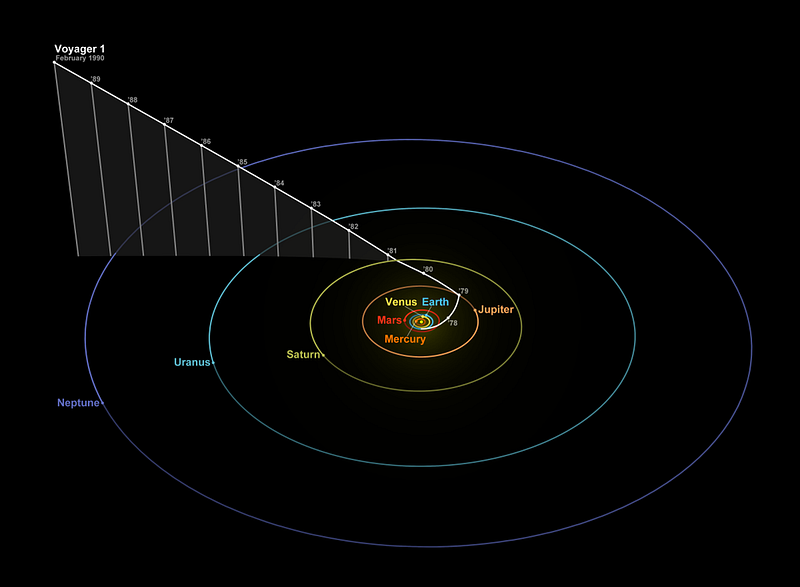

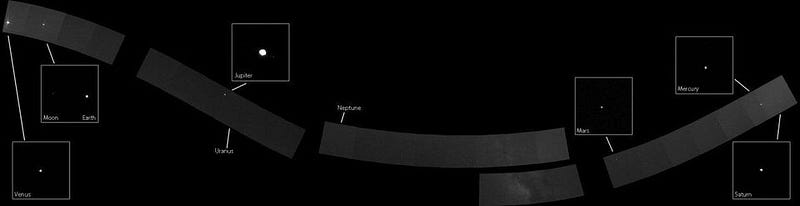

But on February 14, 1990, at the urging of Carl Sagan, Voyager 1 did something for which it had never been designed: it turned around and imaged the planets of the Solar System, one at a time, and transmitted that data back to Earth. From such a great distance — 6 billion kilometers, or 3.7 billion miles — it created a one-of-a-kind family portrait of our home that had never been seen before.

It’s hard to appreciate the scale of this image, or how tiny each of the planets are compared to the distances between them. To help you visualize it, I’ve written the numbers out, and you should remember that Voyager 1 is approximately 6,000,000,000 kilometers away from all the worlds imaged here.

First off, though, I want you to appreciate where Voyager 1 was physically located when these images were taken and stitched together, as it’s hard to appreciate the imaging work and the scale without a proper sense of where all these planets were located relative to Voyager 1, the Sun, and each other.

Here’s what this mosaic of images saw:

- The Sun is a whopping 1,400,000 kilometers across, which means it takes up 48″ (or 0.013°) as seen from Voyager 1 in this image: about the size Jupiter appears from Earth. This corresponds to about 24 pixels in the narrow-angle camera at this distance. Even with the darkest filter and shortest exposure times, it oversaturated all of Voyager 1’s cameras.

- Mercury, with a diameter of 4,900 km, is only 58,000,000 km from the Sun. It would take up just 0.17″ (or 0.05 pixels) as seen from Voyager 1, but was too close to the Sun to be imaged here.

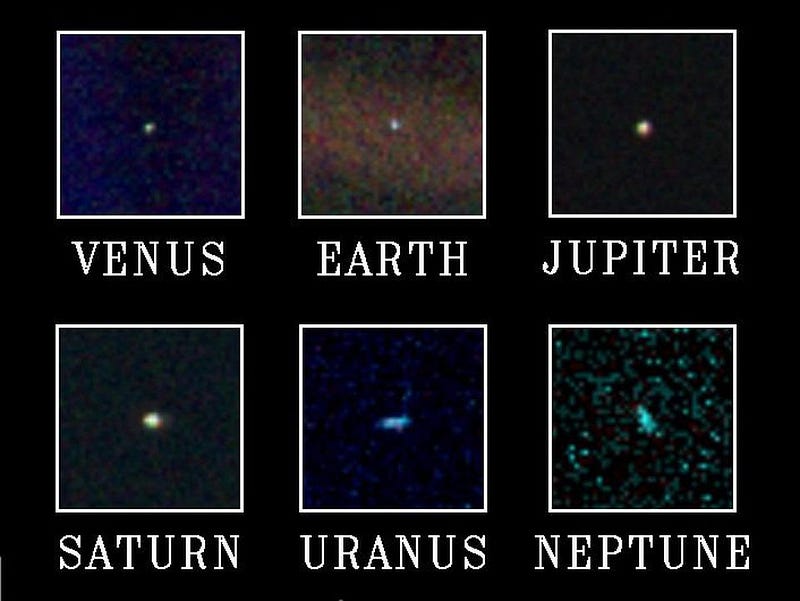

- Venus, with a diameter of 12,100 km, is larger, brighter, and farther from the Sun than Mercury, and takes up about 0.11 pixels.

- Earth, with a diameter of 12,700 km, is the famed “pale blue dot” imaged here. It takes up 0.12 pixels in Voyager 1’s narrow angle camera.

- Mars, with a diameter of 6,800 km, is too small and faint, and was lost due to the bright glare of the Sun. It would take up 0.07 pixels if it had been imaged.

- Jupiter, though, is huge: it has a diameter of 140,000 km. It takes up 4.8″ (or 2.5 pixels) in Voyager’s camera, and thus appears as more than 1 dot.

- Saturn is nearly as large: 116,000 km. Due to its relatively closer proximity to Voyager 1, it takes up the same angular size as Jupiter. Hints of its rings are visible.

- Uranus, although still a gas giant, is much smaller: 51,000 km. It appears as more than a single pixel only because of Voyager’s motion; it took up less than 1 pixel in the camera, and was on the wrong side of the Sun for quality imaging.

- Neptune, finally, is comparable to Uranus: 49,000 km in diameter, and suffers from the same problem as Uranus. It, too, is less than a pixel in Voyager’s camera.

But the most striking thing about these pictures is what Voyager 1 cannot see. In the single pixel that is Earth, all we can see is its average color and brightness. We cannot see its phase; we cannot see clouds, oceans, or continents; we cannot see our Moon. We cannot see the lights that illuminate our nighttime side. We cannot see our cities, monuments, or any signs of human activity. From 6 billion kilometers away, we are only a dot.

We have not even reached cosmic scales in this image. The Sun is still 8 million times brighter than the next brightest star, with the closest exoplanets approximately 1,000 times more distant than the ones in our Solar System. And still, even at such a close distance, there are no visible signs that anything of interest exists on planet Earth.

For thousands upon thousands of years, humans have warred with one another for control over the resources found on tiny, minuscule fractions of this world. Nations have risen and fallen; generations of people have been persecuted, enslaved, or victimized by genocide; individuals have strived to find friendship, love, and meaning amidst the struggle of existence.

At the same time, we are no longer limited by planet Earth itself. Through the advances of science, the development of technology, the spirit of collaboration and teamwork, and the pooling of our collective resources, we have not only come to comprehend the laws governing reality, but we’ve begun to both understand and explore the Universe around us. This pale blue dot is presently home to us all, but our descendants may yet venture farther than we ever will.

Today marks the 29th anniversary of the first-ever family portrait taken of the worlds in our Solar System, from as far away as we’ve ever ventured. The Voyager spacecraft, along with the Pioneers and New Horizons, all continue to speed away from our Sun, and all will eventually wind up in interstellar space. Voyager 1, to as far as we can extrapolate, will remain the most distant human-made object from Earth into the arbitrarily far future.

Yet it’s still operational even today. The family portrait it took on February 14th, 1990, was taken at the urging of Carl Sagan, and remains one of our most iconic views of our fragile home world ever to grace humanity.

20 years later, NASA’s Messenger mission, which is our most extensive mission to the Solar System’s innermost world, did its best to take a similar family portrait. With a better camera but much closer to the Sun, it was able to image the innermost six planets, as well as Earth’s and Jupiter’s large moons, but could not resolve Uranus or Neptune at their great distances.

A single composition from a single spacecraft that captures all 8 planets, along with the Sun, has still never been achieved. There is no scientific value attached to it, but sometimes, a single view that can bring us all together and make us appreciate how alone we truly are in the Universe is worth more than any new knowledge we can glean.

We are at a critical moment in the development of civilization. Our world has advanced to where we are today because of how we’ve invested in education, scientific inquiry, and exploration of the unknown. These are endeavors that have no clearly quantifiable return-on-investment; sometimes, you don’t find anything new when you venture into new territory.

But sometimes you do. 22 years before the Pale Blue Dot, Bill Anders became one of the first three humans to travel to and orbit the Moon. He took the iconic “Earthrise” photo, shown above. His words back then still resonate today:

We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.

As far as we know, there is no one else in the Universe yet aware of our presence. All signs indicate that we have yet to make contact with intelligence beyond our world. Now is the most important time to reinvest in the future of the human enterprise. Let us never forget what we are in the grand scheme of things. It is up to us to make the future of humanity the greatest one we are capable of creating.

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.