Messier Monday: A Cinco de Mayo Special, M4

Although we’re all under the same skies, those at Mexican latitudes will especially enjoy this one tonight!

“Rest is not idleness, and to lie sometimes on the grass under trees on a summer’s day, listening to the murmur of the water, or watching the clouds float across the sky, is by no means a waste of time.” –John Lubbock

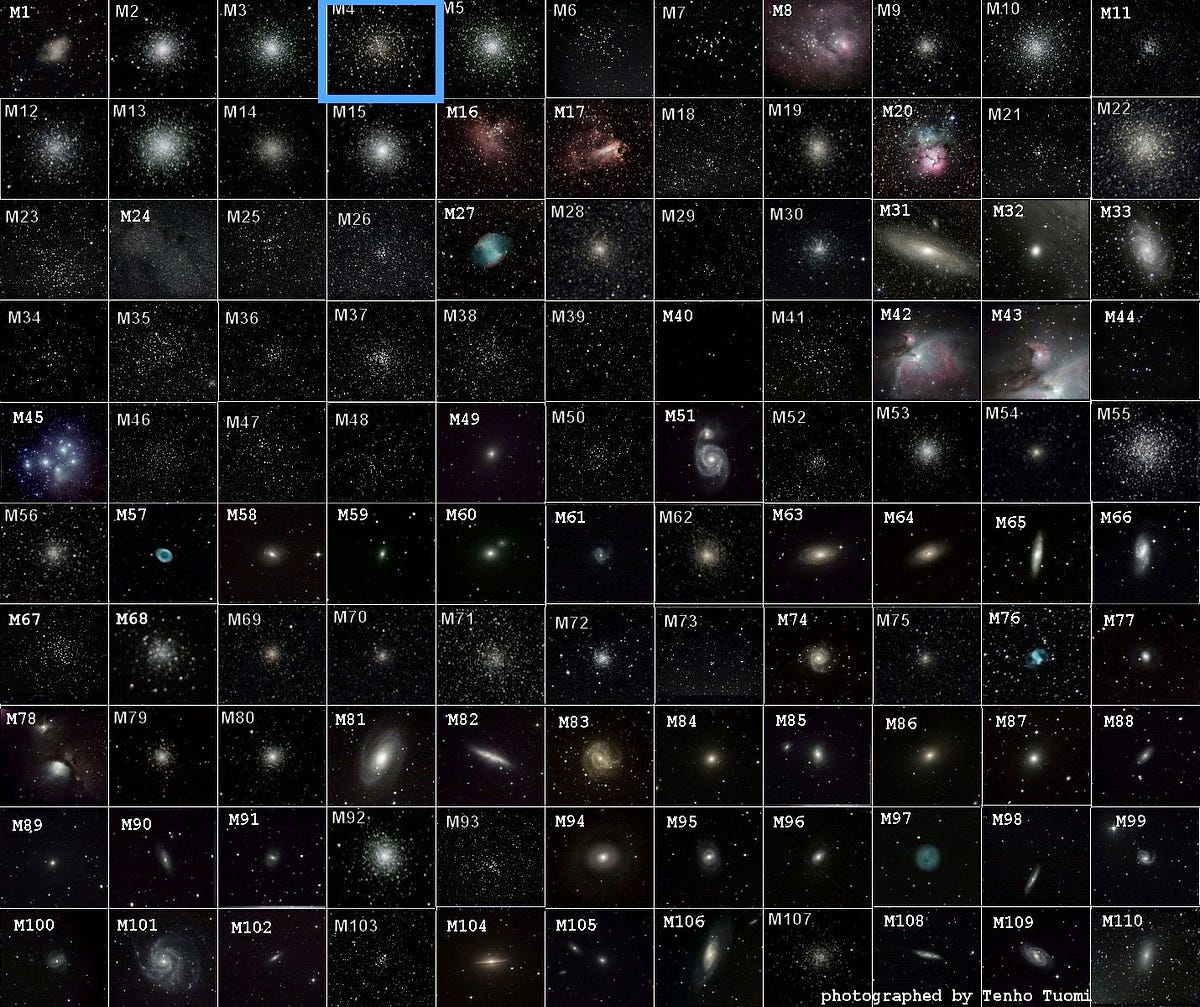

Each Monday since late 2012, we’ve been taking an in-depth look at one of the 110 deep-sky wonders that make up the Messier Catalogue, the first accurate catalogue of star clusters, galaxies and nebulae visible with only a modest telescope ever created. Although I normally showcase objects visible from my latitude (45° N) in the early part of the night, for today — cinco de Mayo (May 5th) — I thought it only appropriate to showcase an object that rises early (at 8 PM) at Mexican latitudes of 19° N, even though observers as far north as I am will have to wait an extra three hours.

You see, from any point on Earth, only half of the night sky is visible at any given time. After the Sun sets, different slices of the celestial skies become visible as the night goes on, providing skywatchers with a chance to glimpse a variety of stars, constellations and deep-sky objects. For today’s Messier Monday, even though the Moon will be out and illuminating the sky, it’s still a fantastic occasion to view open and globular star clusters, and that’s why Messier 4 makes the perfect object for tonight.

Let’s take a look at how to find it.

Those of you — like me — who live at high northern latitudes might be used to using the Big Dipper as your main point-of-reference, following the “arc” of the dipper’s handle to the bright orange giant Arcturus, and then “speeding on” to prominent blue Spica. But from more southerly latitudes, the Big Dipper isn’t a reliable sight; in fact, the famed Southern Cross will be visible in the South at about 10 PM from Mexico tonight!

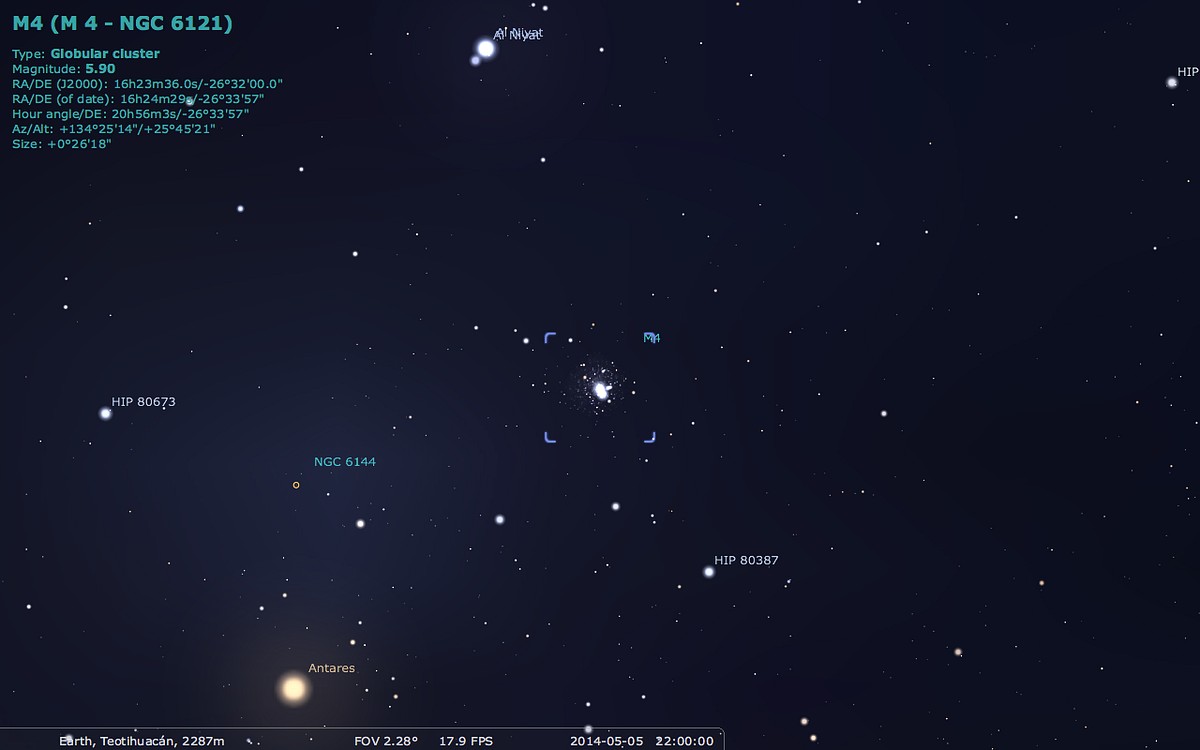

Instead, you’ll want to find another very bright giant — Antares, the 15th brightest star in the night sky — which can be found tonight (although this is temporary, as planets wander!) by jumping from Mars to Spica to Saturn and then down to Antares, the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius.

Although it’s by far the brightest star in its vicinity, there are also a number of naked-eye stars close by. The quite prominent Al Niyat (σ Scorpii), for instance, is just two degrees away back towards Spica, and is bright blue in contrast to the red Antares. If you’re looking with a wide-field eyepiece, a pair of binoculars or a low-powered telescope, Messier 4 can be found roughly in between these two stars, just slightly (maybe 0.5°) south/west of the imaginary line connecting them.

And make no mistake about it: this is a spectacular object even through very modest instruments! Messier 4, out of all 29 of the globular clusters identified by Messier himself, is the closest one to us, and the only one Messier was able to resolve into individual stars. He described it thus:

Cluster of very small [faint] stars; with an inferior telescope, it appears more like a nebula; this cluster is situated near Antares & on its parallel.

To Messier, this globular cluster might have looked something like this.

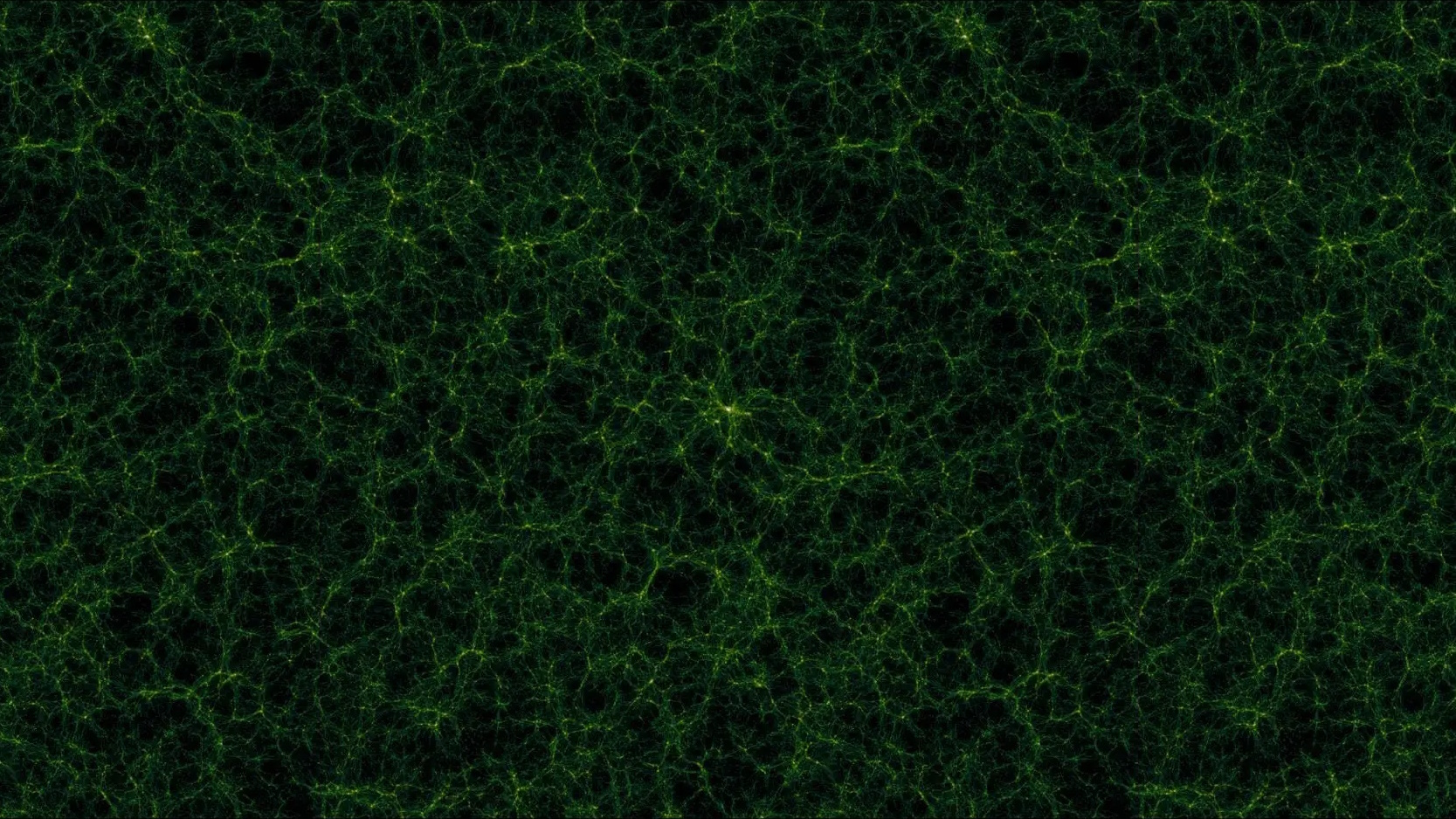

Located a distance of just 7,200 light-years away, this dense cluster of stars has a mass of around 67,000 Suns, and completes an orbit every 116 million years that takes it from just 2,000 light years from the galaxy’s center all the way to 20,000 light years away. Twice per orbit, it passes through the plane of the galaxy, and each time, gravitational interactions likely strip it of some of its stars, meaning it was very likely larger and more massive in the past!

By looking at the individual stars inside, we find that the amount of heavy elements present — things like Carbon, Oxygen, Silicon and Iron — are far less abundant than they are in our Sun: there’s just 8.5% as much Iron, for example. The reason for this is that globular clusters (like Messier 4) are some of the oldest structures in the Universe, formed very shortly after the Big Bang and stripped of potentially star-forming gas subsequently.

Messier 4 is no exception, with an estimated age of 12.2 billion years, which explains why there are so few blue-white stars inside. This age means that the stars present inside were formed most recently in an episode occurring just 1.6 billion years after the Big Bang, when the Universe was only 12% its current age, and what remains today is what’s left after more than twice the age Sun and over 100 orbits of this cluster, where it passed through the galactic plane an estimated 210 times!

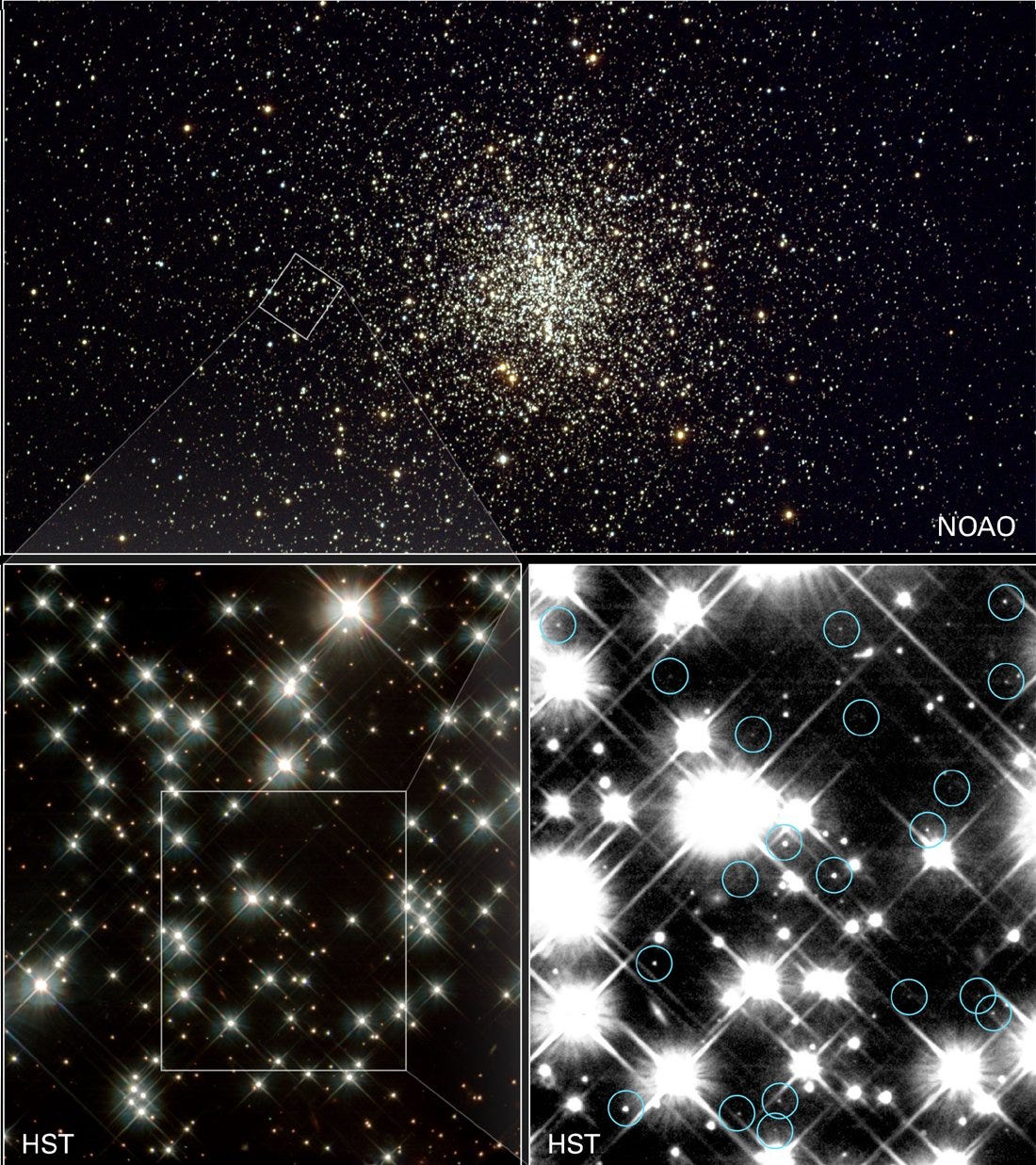

Because this cluster is so old, you might expect there would be a large number of white dwarfs and neutrons stars inside; remnant from prior generations of stars that burned through all of their fuel and died many billions of years ago. Not only are there pulsars (spinning neutron stars) located inside, but Messier 4 is one of the most prolific known sources of white dwarf stars. Thanks to the Hubble Space Telescope, we’ve been able to identify huge numbers of them scattered among the other stars inside.

This is only possible because of Messier 4’s close proximity to us! With tens of thousands of stars in a region of space just 75 light years in diameter, this is actually one of the less concentrated globular clusters around, but that doesn’t mean what’s actually inside isn’t spectacular!

Imagine, if you will, a pulsar (spinning neutron star) orbiting a white dwarf, with a huge gas giant planet 250% the mass of Jupiter in there as well. This exact system has been discovered (and is located in the green circle, above), and is known as PSR B1620-26. The white dwarf inside that circle is 13 billion years old, meaning it likely pre-dates the final episode of star formation that occurred in this globular!

Whether you take in the entire cluster in a wide-field view or just narrow in on the core area, there’s a spectacular beauty in any dense, globular cluster of stars that’s unlike any other structure in the Universe.

Normally, I’d show you the Hubble image last, as it’s normally the most spectacular. But in the particular case of this globular cluster, its present location near Antares, a red giant that’s creating its own nebula of gas around it, and Al Niyat, a blue giant blowing off gas as well, means that wide-field views highlighting the spectacular color differences simply blow all other views away.

This is one of the brightest, nearest globulars visible from Earth, and I can think of no better way to celebrate the night of cinco de Mayo than with this spectacular deep-sky wonder! And if you need more targets to tickle your fancy, why not take a look back at all the previous Messier objects we’ve examined:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back again next week for another deep sky wonder and another tale of a piece of our nearby Universe, only here on Messier Mondays!

Have a comment? Leave it at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!