Is Herd Immunity Possible With A Large Vaccine-Hesitant Population?

Here are the best answers science has to a myriad of commonly asked questions.

Over the past 12 months, the status of humans on planet Earth has changed dramatically. The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has, at the time of this writing:

- infected over a confirmed 121 million people worldwide,

- resulted in the deaths of at least 2.68 million people,

- and presently has over 20 million active infections,

with the United States of America leading the world in all three statistical categories. The year 2020 marks the first year since 1947 where 1% or more of all Americans that were alive at the start of the year died during that calendar year, and already over 186,000 Americans have died of COVID-19 during 2021.

The hope of many has been that the recent slew of developed vaccines will stop the virus in its tracks. With many vaccines having proven safe and effective in robust clinical trials — including the Moderna, Pfizer, and Johnson & Johnson vaccines — they’re now being mass produced, with the goal of eventually immunizing every adult, adolescent, and child who can be vaccinated. However, a large segment of the population is currently refusing the vaccine, imperiling the effort to stop the spread of COVID-19. Here’s the science of how herd immunity works (or doesn’t) in the face of a large, vaccine-hesitant population.

What is herd immunity? Herd immunity is a phrase that’s been used very often over the past year, but remains poorly understood by the general public. The idea is that a deadly disease, much like an apex predator, can easily overcome an individual, isolated prey animal, particularly if the animal is vulnerable or otherwise weak. The isolated and injured zebra stands little chance against a lion or a pack of lions; an immunocompromised individual similarly stands little chance against getting infected — and having that infection be potentially lethal — by a deadly disease.

However, even an injured, elderly, or otherwise infirm prey animal can survive a predator’s attack if the herd is around to protect it. By placing the strongest, most predator-resistant herd animals on the outskirts, where they’ll face off against the predators, the more vulnerable herd animals can survive in relative safety, due to the protection that the herd offers. The analogy starts here: with the idea that some herd animals are, in a sense, “immune” to those predators. Those herd animals offer a sense of protection to the weaker herd animals, and can keep the entire herd safe, including the injured, weakened, elderly, ill, or otherwise vulnerable members.

In human society, we have similarly vulnerable members. COVID-19 has, over the past year, become notorious for just how disproportionately lethal it is among the elderly, the immunocompromised, and the obese, among other comorbidities. In addition to that, there are some members of society right now that — depending on where they live — may not eligible for vaccination, as the vaccines have not yet been proven safe and/or effective in those specific populations. They include:

- children under the age of 16,

- people with certain specific pre-existing health conditions such as HIV/AIDS,

- and people who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

The idea of herd immunity is that if a high enough percentage of the population has what’s known as “sterilizing immunity” to a certain disease, their immunity can protect the otherwise vulnerable members of society from acquiring the disease. Sterilizing immunity means that a pathogen will not infect, cause illness in, or be transmissible by an immune individual. Some vaccines, like smallpox and measles, confer sterilizing immunity on the vaccinated; others, like the hepatitis B vaccine, will protect the vaccinated individual from ill effects, but the individual can still contract the illness and pass it along to others.

Can COVID-19 vaccines keep unvaccinated people safe? The reality of the situation is that the various vaccines that are out there today don’t provide 100% sterilizing immunity, but are at least substantially effective at preventing the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The extent to which it’s effective has not been fully quantified, but it appears that:

- the viral load experienced by vaccinated, infected individuals is significantly lower than the viral load experienced by unvaccinated, infected individuals,

- that the likelihood of viral transmission and of the severity of infection is directly related to the viral load one encounters,

- and that the immune response in vaccinated individuals increases over time once the final dose of a vaccine (or vaccine series, in the case of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines) is received.

In other words, the more people are vaccinated, and the longer it’s been since their last vaccine dose, the lower their viral load will be, even if they do carry an infection. This is important, because it is a way that each one of us can help. With each new person that gets vaccinated, we offer some additional level of protection to all individuals in our society, even those of us who are unvaccinated.

What about mutant strains and variants of the novel coronavirus? This is a good — and scary — question. Each time a living organism replicates, even a virus whose classification as “living” or “organism” is highly debatable, it does so by making a copy of the nucleic acids that determine its genetic code. Even with the error-checking mechanisms that have evolved over billions of years, mutations do occur from generation to generation.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there are only some ~30,000 base pairs in its entire genetic sequence, and a few select mutations can result in a novel strain that could be either:

- more or less deadly,

- more or less infectious,

- and more or less resistant to the immunities that various vaccines confer.

The way to suppress mutant strains and minimize the novel variants that will emerge is simple: prevent as many infections as possible. The more infections there are, the greater the number of new viruses that are created. These viruses can be passed onto other human hosts, and potentially create new variants, some of which may be vaccine-resistant to one or — in the worst imaginable scenario, all — of the immunities which the various vaccines confer.

What about the potentially deadly side effects associated with the vaccines? Unfortunately, this is a pervasive fear among the general population, despite the fact that it’s completely ill-founded. This is one of the major points of clinical trials: they exist to identify any possible ill-effects that will emerge from a vaccine. Can it induce an allergic reaction? Can it interfere with patients that possess certain comorbidities or risk factors? Will it cause cardiovascular events, pulmonary obstructions, organ failure, or other potentially deadly effects?

The vaccines that are available today — each and every one of them (except, arguably, for the Sinovac-developed CoronaVac) — have passed a series of rigorous, peer-reviewed, large-scale clinical trials, finding no risk factors that were greater among the vaccinated group than the non-vaccinated group. Nonetheless, there will be instances where people get the vaccine and then, seemingly immediately, get sick and/or die.

This is not a valid argument against getting a vaccine. Approximately 150,000 people die every day across the world, roughly two-thirds of which are from natural causes associated with old age. So long as those deaths occur at equivalent rates in vaccinated and unvaccinated populations, the scientific conclusion will be that there is no increased risk of mortality associated with getting the vaccine.

Other than that, you can expect that you may encounter some minor symptoms of illness when you get vaccinated: pain at the injection site, body aches, fatigue, headache, dehydration, fever and/or chills, etc. You should follow the advice of your medical professionals as far as how you cope with any symptoms that may arise. Don’t be alarmed, however; that’s simply your body having an immune response, which is a sign that the vaccine is working as expected.

So what percentage of people need to get vaccinated for us to reach herd immunity? This is the question that many people have been asking since the start of the pandemic, with many presuming that herd immunity would become inevitable once a certain percentage of the population have either been infected (and recovered) or vaccinated.

The short answer is, to be honest, doubly disappointing. We aren’t sure whether herd immunity can ever be reached for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and even if it can be reached, we don’t know what that percentage is, but it’s suspected to be a high number: greater than 70% of the population, and possibly as high as 90% or more.

Here are the reasons why.

Why might herd immunity be an impossibility? There are two primary reasons that cast doubt on the existence of herd immunity.

- The fact that the virus mutates, and that mutations might evade the immunity that either vaccines or prior infection confers.

- The fact that the immunity that either a vaccine or a prior infection confers may not be a very effectively sterilizing immunity.

Herd immunity, remember, is predicated on the assumption that there are immune individuals that can stop the spread of the disease: they cannot get infected and they cannot infect others.

The more infections there are, the greater the risk of mutations, and in particular of immunity-evading mutations. If the wrong combination of mutations occurs, it’s possible we could be right back at square one: where a new variant emerges that no one has immunity against. Just as some variants have emerged that appear to be deadlier than the original strain, the nightmare scenario is the emergence of a strain that’s both more contagious and more deadly than SARS-CoV-2, and that no one has effective immunity against.

Can outbreaks still occur if almost everyone has some type of immunity? The unfortunate answer is “yes,” and we need look no further than a very common illness for an example: measles. Measles, fortunately, is a disease that we have a safe and effective vaccine for, and that vaccine does provide a completely sterilizing immunity to those who receive it. The difficulty with measles as an infectious disease, however, is that it’s extremely contagious: more than three times as contagious, as measured by its R0, than SARS-CoV-2.

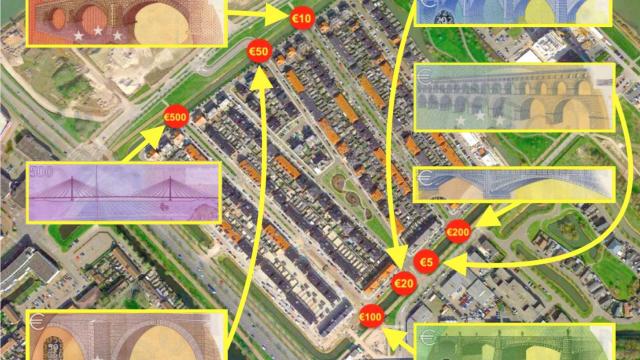

In practice, approximately ~95% of the population needs to be vaccinated against measles to provide herd immunity. In places where non-medical exemptions are granted — including religious or personal exemptions — enabling people who can be vaccinated to opt out, outbreaks and even local epidemics have ensued. Vaccine hesitant individuals have led to a resurgence of many diseases that could otherwise have been eradicated. That should be the goal: eradication of deadly diseases, and successfully vaccinating everyone who can medically be vaccinated is the most effective weapon against these illnesses.

So what should you do? At this point in time, the most effective set of measures you can take to protect your own health and the health of others is simple. First, you should get whatever approved vaccine (or course of vaccines) are available to you as soon as you’re able to get them. You should continue to wear masks and socially distance whenever out in public, and to continue to minimize contact with individuals — particularly unvaccinated individuals — from outside your own home. And, if at all possible, you should encourage those around you to do the same.

There is a war going on right now that most of us are aware of, but that nonetheless we cannot see: between an infectious virus and human beings. The best measures we can take, both collectively and individually, are to minimize the likelihood of infecting ourselves and others, as well as to minimize the severity of any possible infections. Vaccinations, social distancing, minimizing in-person contacts, and mask-wearing while in public are the best interventions we have to make that happen.

Now is a critical time in the battle against COVID-19, and our collective behaviors over the next few months will determine whether the pandemic is brought to an end by the time summer comes along, or whether this affliction remains with us for much longer: potentially for years to come. In the war between this infectious virus and human beings, may everyone who reads this choose the side of the humans.

Starts With A Bang is written by Ethan Siegel, Ph.D., author of Beyond The Galaxy, and Treknology: The Science of Star Trek from Tricorders to Warp Drive.