Ask Ethan: How Do Hawking Radiation And Relativistic Jets Escape From A Black Hole?

If nothing can escape from beneath the event horizon, where do these phenomena come from?

The most important feature of a black hole is that it has an event horizon: a region of space where the gravitational field is so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape from it. How, then, do we explain the matter and radiation that we both see and predict should come from them? That’s what Russell Sisson wants to know, as he asks:

Everything you read about a black indicates that “nothing, not even light, can escape them”. Then you read that there is Hawking radiation, which “is blackbody radiation that is predicted to be released by black holes”. Then there are relativistic jets that “shoot out of black holes at close to the speed of light”. Obviously, something does come out of black holes, right?

Matter and radiation can definitely come towards us, originating from the black hole’s location. But does that mean something escapes from a black hole? Let’s find out!

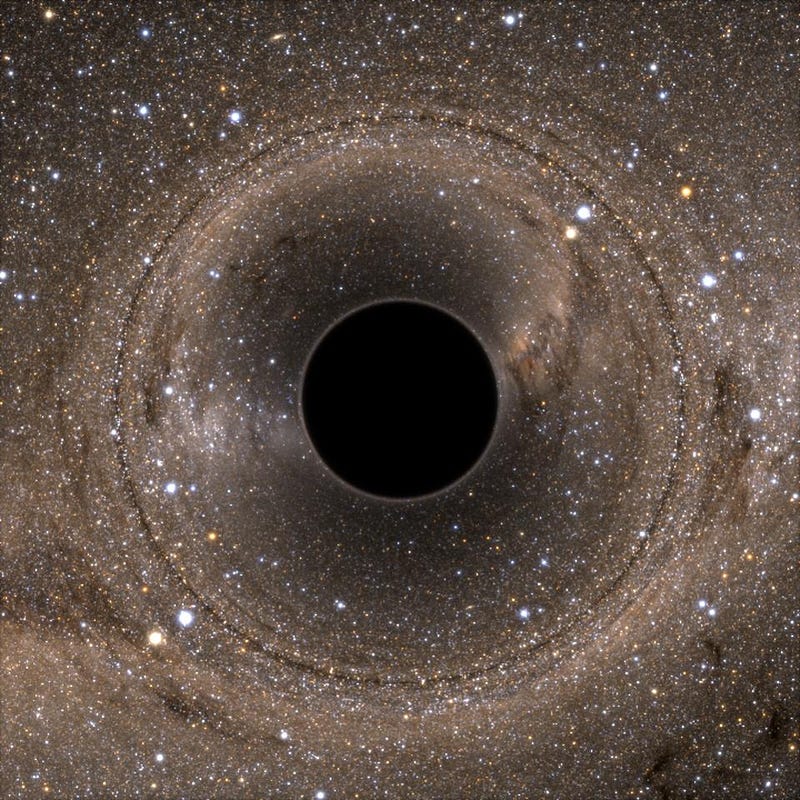

When we talk about a black hole, it’s important to recognize what we mean. If you put enough mass together in a small enough volume of space, the curvature of spacetime will become so large that a ray of light, no matter what direction it propagates in, will inevitably arrive back at the central singularity. The escape velocity — or the speed at which you’d need to move to overcome the black hole’s gravitational pull — is greater than the speed of light. A consequence of this is that there’s a critical region, or an event horizon, where once you cross inside of it, you can never get out. Things that are inside the event horizon always hit the singularity; things that are outside can either escape or fall in, dependent on their properties.

There are, though, real particles and radiation, both observed and theorized, that does originate from a black hole. Accretion disks are a spectacular example. Imagine you’re a particle outside of a black hole’s event horizon, but gravitationally bound to it. The strong gravitational pull will cause you to move in an elliptical orbit, where your fastest speed corresponds to your closest approach to the black hole. So long as you don’t cross the event horizon, you shouldn’t ever fall in. Occasionally, if there are enough particles in orbit, you’ll interact with the other ones, experiencing inelastic collisions and friction. You’ll heat up, be compelled to move in a more circular orbit, and eventually emit radiation.

This radiation doesn’t come from inside the black hole, but from the matter orbiting outside the event horizon.

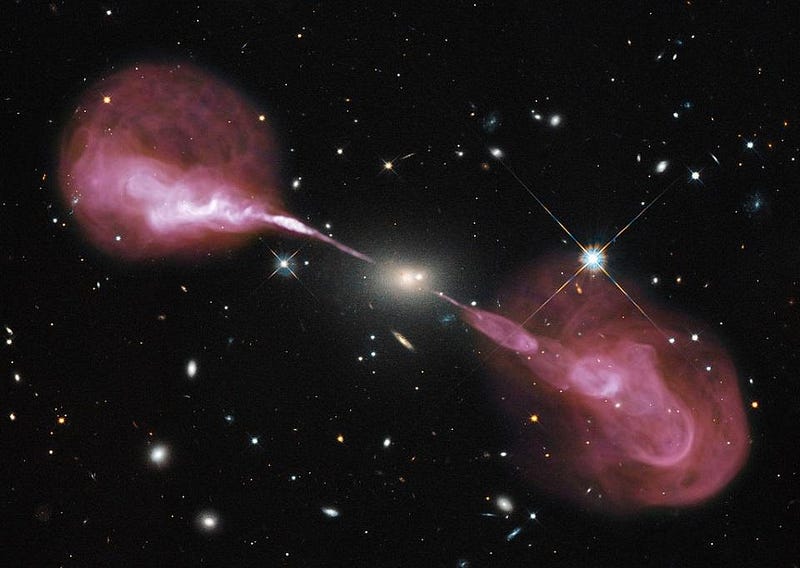

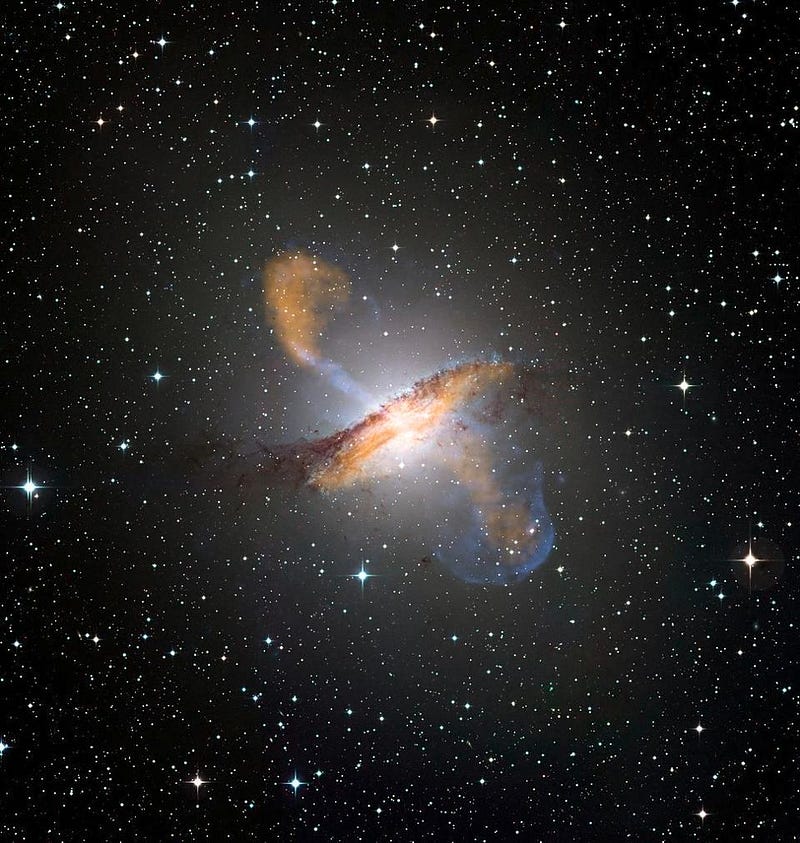

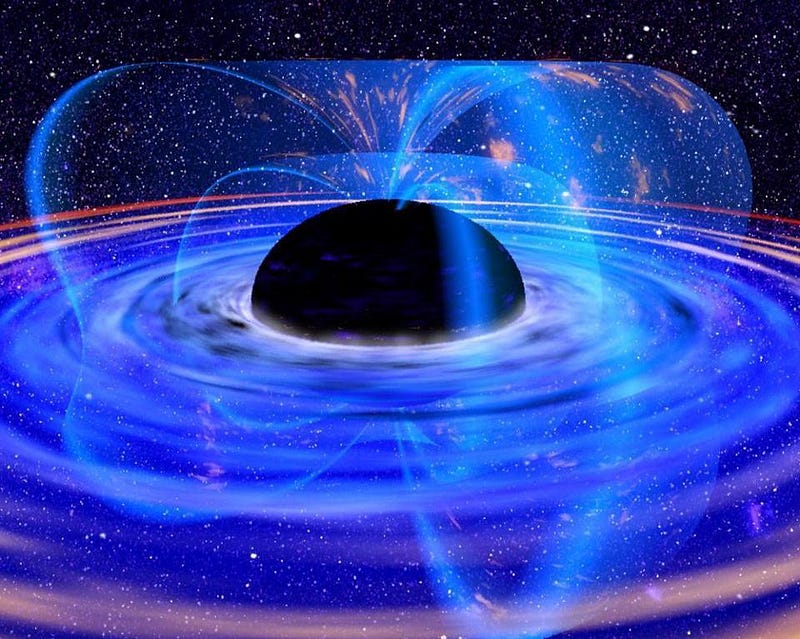

Sure, some of the matter will eventually lose enough energy that it will cross over to the inside of the event horizon, arriving at the singularity and increasing the mass of the black hole. But there’s a lot going on in the vicinity of the black hole. There are charged particles of different signs and magnitudes traveling very rapidly: moving close to the speed of light. Charged objects in motion create magnetic fields, and that causes many of the ionized matter particles to be accelerated in a helix-shape, away from the plane of the accretion disk. These accelerating particles are the origin of relativistic jets, producing showers of particles and radiation when they collide with the material farther away from the black hole.

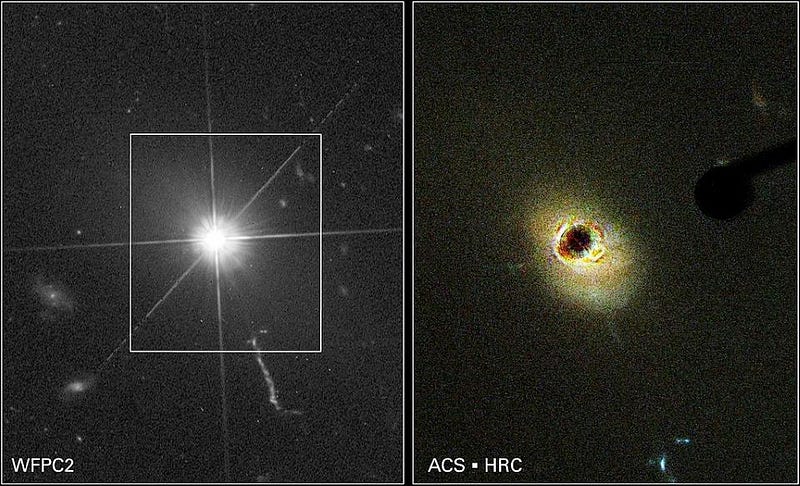

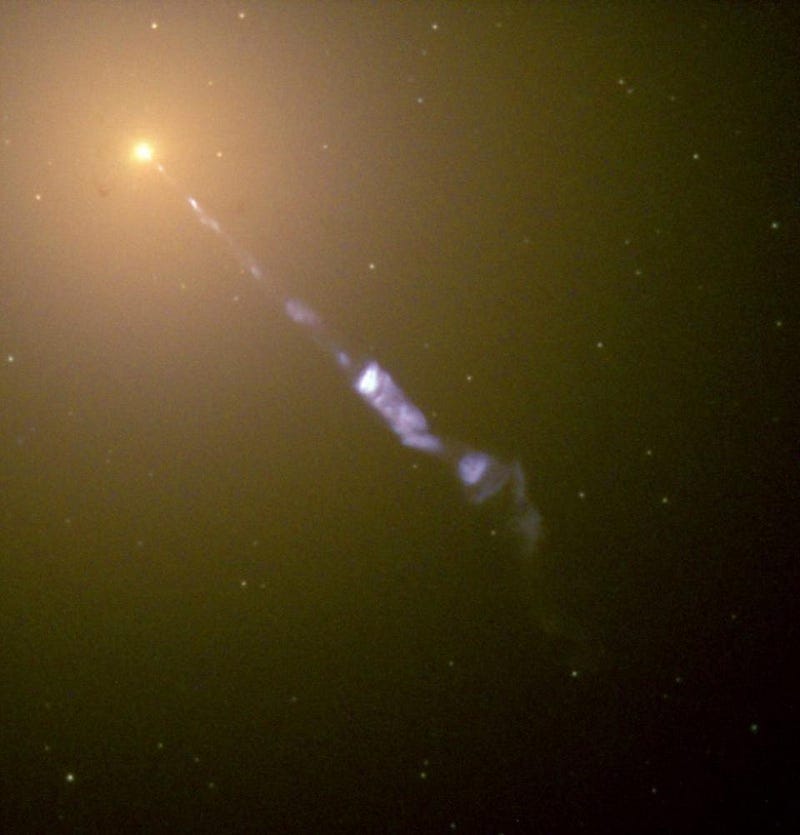

Relativistic jets are a remarkable sight, and in some cases, are so brilliant that they actually appear in visible light. The galaxy Centaurus A has a jet in both directions that becomes large, diffuse and spectacular; the galaxy Messier 87 has a single, collimated jet that extends for over 5,000 light years. Both of these are caused by an active, supermassive black hole that’s many times larger than even the four-million-solar-mass monstrosity at the center of the Milky Way.

For accretion disks and relativistic jets, these are phenomena that are observable around black holes, but nothing is coming from inside the black hole and getting out. For Hawking radiation, however, things get a little more complicated. In theory, you can imagine a black hole that was truly in the vacuum of space, with no matter, radiation, or other masses around it. If the black hole weren’t there, all you’d have was the vacuum of flat, uncurved space governed by the fundamental laws of the Universe. But if you put the black hole there, you have curved space, an event horizon, and the laws of physics. And a consequence of that is that you get omnidirectional radiation with a blackbody spectrum to it: Hawking radiation.

The problem with conceptualizing Hawking radiation is the following: all of the radiation originates from outside the event horizon, but the only place to draw energy from is the mass inside the black hole itself. For every quantum of energy (E) released in the form of Hawking radiation, the mass of the black hole (m) has to decrease by an equivalent amount. How much is that? By exactly the amount that Einstein’s most famous equation predicts, E = mc2. But how, then, can radiation from outside a black hole be caused by mass that’s inside a black hole, particularly if nothing can escape the event horizon?

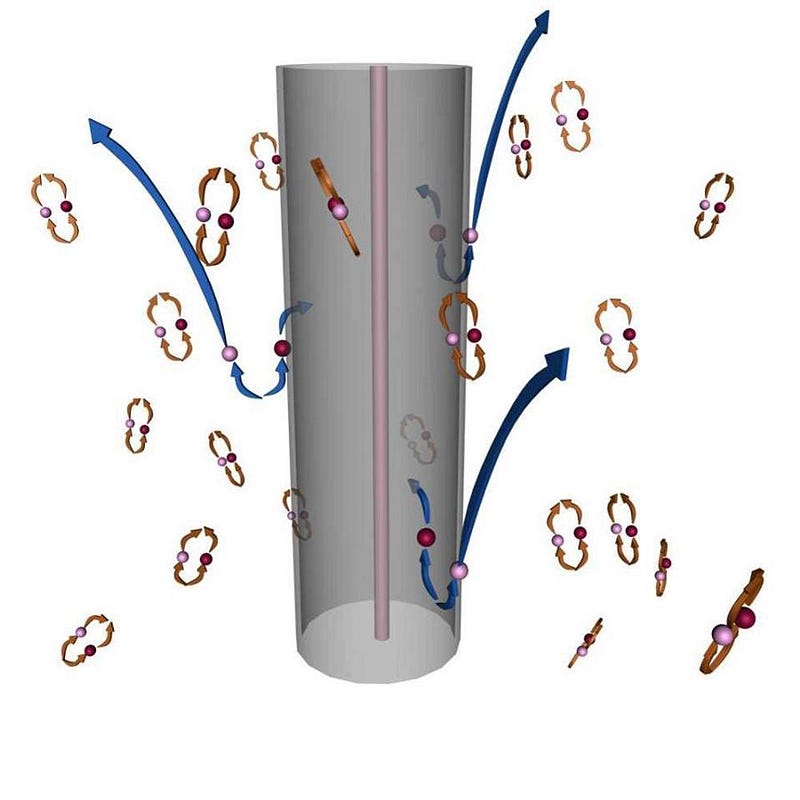

The most common explanation — given by Hawking himself — is also the most wrong. One of the ways you can visualize vacuum energy, or the energy inherent to space itself, is with particle-antiparticle pairs. Empty space, because its zero-point energy is a positive value (rather than zero), can’t be visualized as altogether empty; you need something to occupy it. Combining this fact with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, you arrive at a picture where matter-and-antimatter pairs pop into existence for a very brief amount of time, before annihilating away back into the nothingness of empty space. When one member is outside the event horizon but the other falls in, the “outside” one can escape, carrying energy away, while the “inside” one carries negative energy and decreases the mass of the black hole.

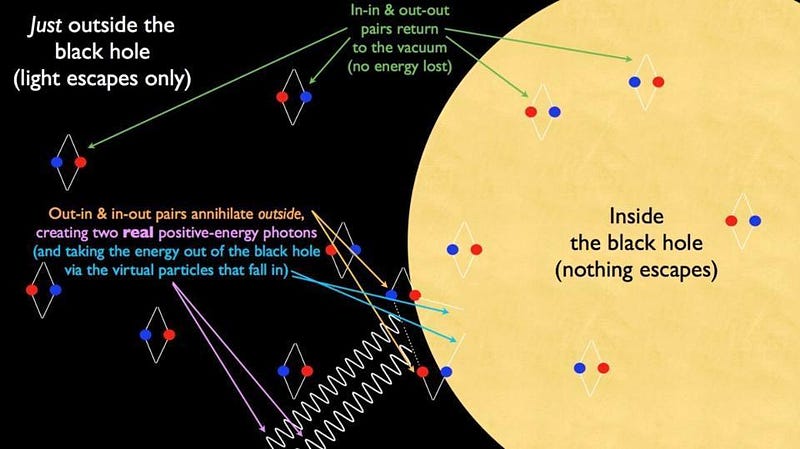

First off, this visualization is not for real particles, but virtual ones. They are calculational tools only, not physically observable entities. Second, the Hawking radiation that leaves a black hole is almost exclusively photons, not matter or antimatter particles. And third, most of the Hawking radiation doesn’t come from the edge of the event horizon, but from a very large region surrounding the black hole. If you must adhere to the particle-antiparticle pairs explanation, it’s better to try and view it as a series of four types of pairs:

- out-out,

- out-in,

- in-out, and

- in-in,

where it’s the out-in and in-out pairs that virtually interact, producing photons that carry energy away, where the missing energy comes from the curvature of space, and that in turn decreases the mass of the central black hole.

But the true explanation doesn’t lend itself very well to a visualization, and that troubles a lot of people. What you must calculate is how the quantum field theory of empty space behaves in the highly-curved region around a black hole. Not necessarily right by the event horizon, but over a large, spherical region outside of it. Performing the quantum field theory calculation in curved space yields a surprising solution: that thermal, blackbody radiation is emitted in the space surrounding a black hole’s event horizon. And the smaller the event horizon is, the greater the curvature of space near the event horizon is, and thus the greater the rate of Hawking radiation.

Under no circumstances, however, can we conclude that anything crosses the event horizon from inside to out. Hawking radiation comes from the space outside of the event horizon, and propagates away from the black hole. The loss of energy lowers the mass of the central black hole, eventually leading to total evaporation. Hawking radiation is an incredibly slow process, where a black hole the mass of our Sun would take 10⁶⁷ years to evaporate; the one at the Milky Way’s center would require 10⁸⁷ years, and the most massive ones in the Universe could take up to 10¹⁰⁰ years! And whenever a black hole decays, the last thing you see is a brilliant, energetic flash of radiation and high-energy particles.

These final decay steps, which won’t occur until long after the final star has burned out, are the last gasps of energy the Universe has to give off. In it’s own way, it’s the Universe itself trying, one final time, to create an energy imbalance and an opportunity for the creation of complex structures. When the last black hole decays, it will be the Universe’s final attempt to say the same thing it said at the start of the hot Big Bang, “Let there be light!”

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!

Ethan Siegel is the author of Beyond the Galaxy and Treknology. You can pre-order his third book, currently in development: the Encyclopaedia Cosmologica.