2014’s greatest meteor shower

This weekend, the Geminids arrive, and promise to be the best meteor shower of the entire year!

“Men of genius are often dull and inert in society; as the blazing meteor, when it descends to earth, is only a stone.” –Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Yet for that instant, that brief moment when a meteor blazes through our sky, it has the potential to be the brightest thing around, and the most spectacular sight that’s worth waiting, watching and braving the cold for.

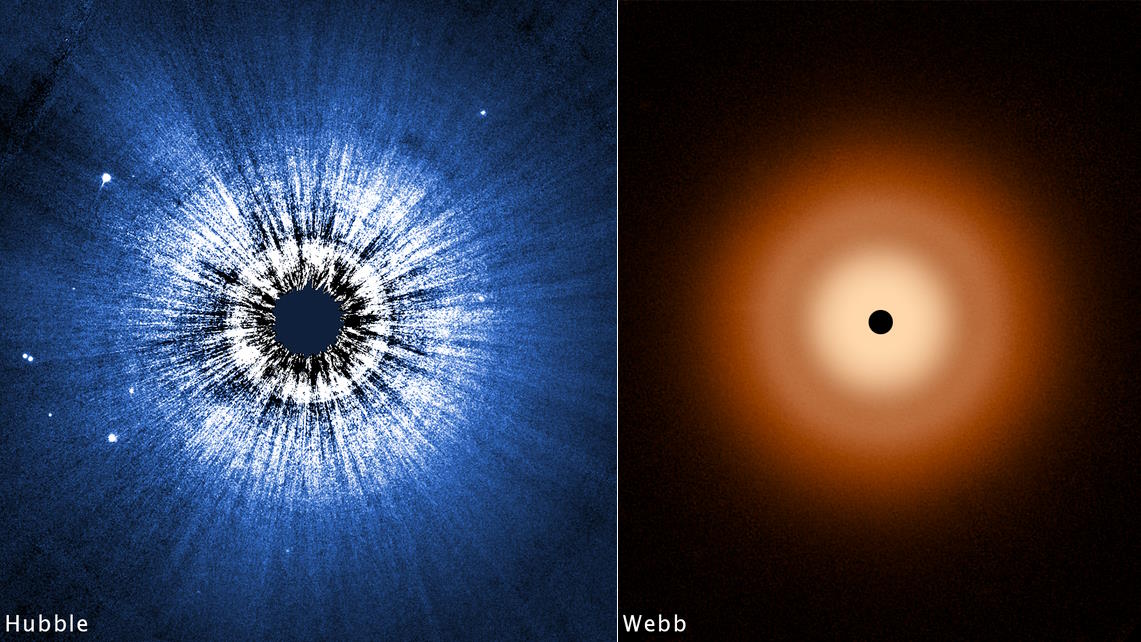

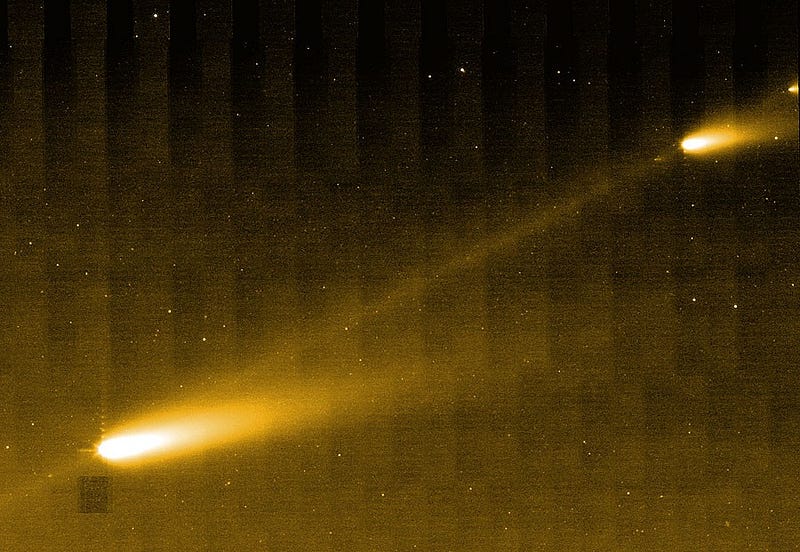

When you see a meteor, what you’re actually seeing is a bit of cosmic dust, usually no bigger than a pebble and often even smaller than a grain of sand, that broke off from a comet or asteroid that orbited a little too closely to the Sun. As the Sun’s energy heated up the orbiting body, and broke small fragments off of it, tiny little pieces of debris break off as well, leading and trailing the orbit of the main body.

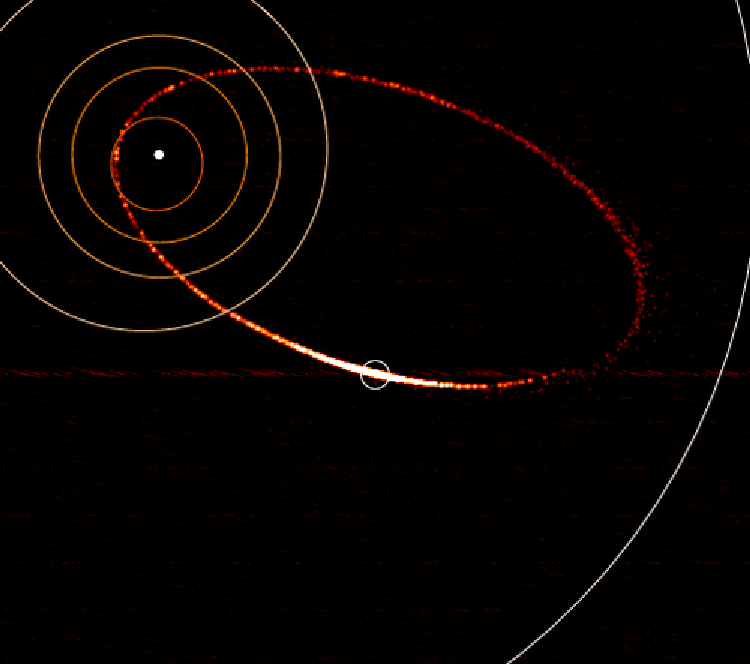

Over enough time and enough orbits, that debris trail gets stretched out along the entire elliptical path.

And when Earth has the good fortune to cross that elliptical path, our great spheroidal world crashes through that debris field! Not only do we move at some 30 kilometers-per-second relative to the Sun, but these little dust grains are moving even faster in their highly elliptical orbit. Even though these particles may be incredibly tiny and low in mass, remember that the formula for kinetic energy is ½ m v^2. So even if your “m” is small, if your “v” is large enough, you can wind up with tremendous amounts of energy!

Another really nice thing about meteor showers is that, as the Earth passes through the debris stream, it always collides with these tiny particles in the same region of the sky. Even though they streak across it in all directions, they always appear to originate from the same location: we call this a radiant. If you keep your eyes loosely focused on one particular location in the sky, and keep an eye out for streaks of light emanating from that place, that’s how you’ll catch the greatest number of meteors.

Well, this coming weekend — and Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights in particular — the Geminids are at their peak. They might not be as famous as some other meteor showers, like the Leonids or the Perseids, but this year, they deserve to be! You see, there are a few things that determine how spectacular a meteor shower display is:

- How dark your skies are. If there’s no moon out, that’s the best.

- How close the Earth is to the middle of the comet/asteroid’s debris stream.

- And how thick that debris stream actually is.

In the case of the Geminids this year, we’re set up for something spectacular.

For one, the Moon reached its full phase all the way back on December 6th, and so it won’t even rise until well after midnight. Since the radiant of the Geminids is right near the star Castor, rising in the northeast at around 7 PM in most places, viewing should be spectacular from about 7 PM until midnight. (Or even later, if you can brave the cold!)

For another, the Geminids don’t originate from a long-period comet, but rather from a relatively close-in asteroid: Asteroid 3200 Phaethon! With an orbital period of only 1.43 Earth-years, 3200 Phaethon is never very far from the Sun, and is always close enough that ices can melt and tides can stretch this rocky body. It also gets very close to the Sun, coming halfway between Mercury and the Sun at closest approach! Therefore, it’s constantly losing mass with every orbit, meaning that its debris stream gets thicker and more dense each and every year!

The Geminids are a relatively new meteor shower: they were only observed for the first time in 1862, where the displays were incredibly weak. Back in the 19th century, you were lucky to see 10 meteors an hour during the Geminids, similar to the flop of this year’s new shower: the Camelopardalids.

But the Geminids are a flop no longer!

Since the Geminids were first discovered, they’ve been intensifying annually. In recent years, the Geminids have been producing over 100 meteors per hour, and this year they’re expected to peak Saturday night, with rates somewhere between 120 and 160 meteors per hour! The only people who’ll have a better view than we do if we have clear skies are the astronauts on board the ISS!

So get out there and look towards the northeast after sunset if you’ve got any sort of clear skies at all; the spectacular rewards will all be worth it. And not only that, but you just might see quite a show! 2011 was a record setting year for the Geminids, with a maximum rate of 198 meteors per hour at peak, and a waning moon that year. This year, the moon has waned even farther, and 3200 Phaethon has had two more passes near the Sun since then. If we’re lucky (no promises), we just might break the record this year!

And if for some reason you can’t get outside or your skies are just clouded out, the Virtual Telescope Project has an online stream for you to observe over your computer, which isn’t a bad consolation prize.

But assuming you have at least one clear night from Friday to Sunday, make the time. We have every reason to hope, so if you’ve got a chance this weekend, get out there, turn off your holiday lights and look up. If you can find Castor in the night sky, give it just five minutes. After you’ve seen a flurry of meteors, you might discover that five minutes simply isn’t enough. And if it touches you the same way it touches me, you might never look at the night sky the same way again.

Leave your comments at the Starts With A Bang forum on Scienceblogs!