Why you should always question your perceptions

- Our perceptions can easily be fooled.

- It’s important to question your perceptions before using them as a basis for beliefs, judgments, and even memories.

- Collaboration and questioning your first impressions can help you better analyze your perceptions for biases and assumptions.

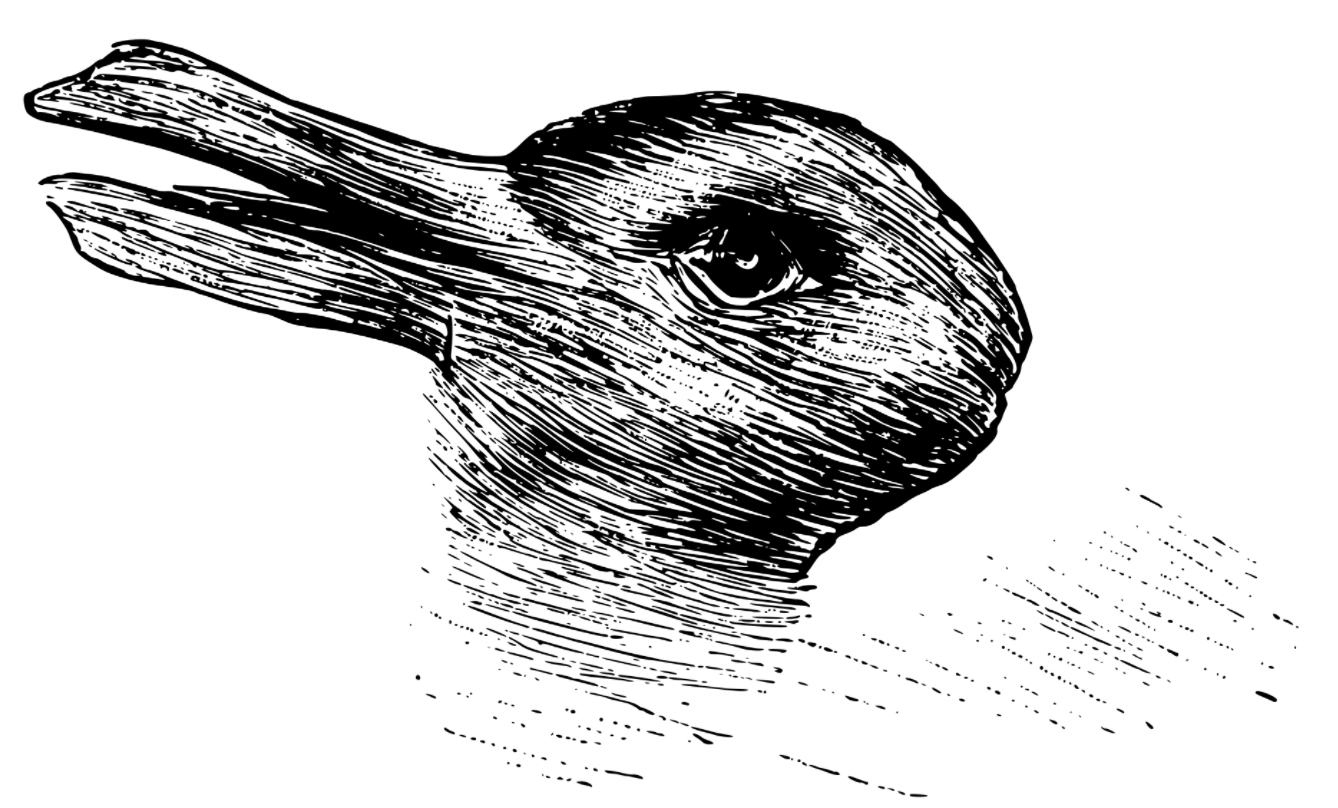

Optical illusions are alluring. People enjoy revealing the hidden rabbit (or duck) in the image below. They’re amused to discover that they can see a triangle where there isn’t one, or chaotic stirrings in an image that doesn’t move. And few seem capable of visiting the Leaning Tower of Pisa and resisting the urge to take a picture of themselves propping it up.

Yet there’s a sinister undertone to these playful visuals. That being: The human mind is easily fooled. Light, the angle of observation, mental shortcuts, and expectations can disfigure our perceptions of objective reality. That goes for anything that relies on perception as a potential source of evidence, such as your beliefs, judgments, and memories. For Amy Herman, art historian and author of Visual Intelligence, these and other quirks in perception signal a need for us to be more cognizant of our limitations and actively assess what we (think) we see.

Missing what’s right in front of you

In an interview with Big Think+, Herman noted how she begins her visual intelligence classes by showing her students the dress.

In case you’re lucky enough not to remember, the dress was a viral internet phenomenon in which people argued over the color of a dress. Some swore it was a black-and-blue dress, others a white-and-gold one. Some even proposed that various hues of red, silver, and brown were part of the mix.

One of the most shared tweets of the moment was by Taylor Swift when she said the whole affair left her feeling “confused and scared.” (Ah, 2015, when the scariest online dustup was about evening wear.)

Herman’s point isn’t to relitigate a social media turf war. It’s that we can’t rely on our immediate perceptions, as even a picture of a dress can prove a barrier between us and objective reality. And, of course, we’re rarely dealing with something as simple as fabric.

“While this is a dumb dress, I don’t really worry about whether you see it as white and gold or blue and black. My concern is when you’re sitting in the meeting, you’re in the operating room, you’re questioning a suspect and two of you walk away with a fundamentally different perception of what you just observed. That’s my concern,” Herman told us.

Test your perception

Herman then shows her class the image below and asks, “Do you see something definitive and unequivocal in this photograph that you could describe to someone who wasn’t looking at it? What is it?”

Try it for yourself:

At this point, Herman noted, a hand or two will go down. She then starts providing hints:

- What you’re looking at is a mammal.

- It walks on four legs.

- It’s a domesticated animal.

Did you figure it out? It’s a cow. Specifically Renshaw’s cow. Dr. Samuel Renshaw used images like these to study perception and used his findings to develop visual exercises to help World War II Navy pilots discern enemy craft quickly and accurately.

If you saw the cow right away, great. If you didn’t, consider how much easier it was to spot that sneaky bovine once you read Herman’s clues. Still can’t see it? Try asking someone else if they can help you define its outline. Once you see it, you won’t be able to unsee it.

Herman’s takeaway for her classes: “It’s very complex what the brain sees and doesn’t see. How do we approach situations when two people see things very differently?”

Question your perceptions

Herman’s exercise suggests two takeaways for how to improve your assessment faculty. The first is that assessment requires practice and a willingness to probe beyond your initial impression.

People are partial to making quick observations and giving them undue weight. Psychologists call this the first-impression bias. For example, if you didn’t see Renshaw’s cow right away, you may have dismissed it as a splotch. While that assessment is understandable, it doesn’t offer a pathway to effective analysis.

And just as an assumption may prevent you from seeing the cow, cognitive biases can blind you to meaningful information or changes to a situation. For example, you may discredit a coworker’s competency if they make a bad first impression, or you may stick with a stock long after its downturn if the initial performance was positive. In both cases, the initial impression should be reassessed as more information comes in.

Broaden your perception through collaboration

The second takeaway is that collaboration is critical to proper assessment. Everyone has their limitations and mental blind spots. Collaboration allows you to tap into others’ perceptions to bolster your assessment prowess.

You could argue cow or no cow, white-and-gold dress or black-and-blue, all day. Or you can realize that perception is full of assumptions on your part. By actively seeking information from others, you gain a fuller understanding of reality.

In the case of Renshaw’s cow, collaboration can be as simple as asking someone to trace the cow’s outline. And while the case of the dress seems like a matter of opinion, it’s not. Through research, collaboration, and some Photoshop know-how, it is possible to solve the puzzle. (And for the record, the dress was black-and-blue.)

All of this is to say, by dedicating yourself to practicing better assessment techniques and making a point to question your perceptions, you can improve your understanding of your perception, how others view the world, and what’s really out there.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Amy Herman’s expert class for your organization, request a demo.