Why the diabolical earworm “Baby Shark” is so popular

The difference between a song people can’t get enough of and a song nobody cares about is…well, no one really knows. And it’s not for lack of trying. Musicians, musicologists and music theorists, statisticians, analysts, and even psychologists have tried for years to figure out the formula. Now they’ve got the slide rules and metronomes out again for a children’s song whose videos have collectively been viewed a jaw-dropping 3.3 billion times. The song is so simple it seems like it couldn’t possibly be the object of such adoration, and yet there it is. “Baby Shark” is a reminder of music’s perplexing hold on the human spirit.

The Baby Shark phenomenon

The song itself appears to be based on a well-worn nursery and camp song going back at least a decade, if not further. It’s not completely dissimilar to the French singalong “Bébé Requin.”

“Baby Shark” began its swim to the top in a 2014 South Korean video from Pinkfong, an educational platform that’s produced thousands of videos for kids. The company’s spokesperson explains to Quartz how the song was composed: “We took a fresh twist and re-created on a traditional singalong chant with our Pinkfong’s Baby Shark.” Pinkfong also added a snippet of Dvorak’s New World Symphony to the front for dramatic effect.

Warning: The song is desperately catchy.

(Pinkfong)

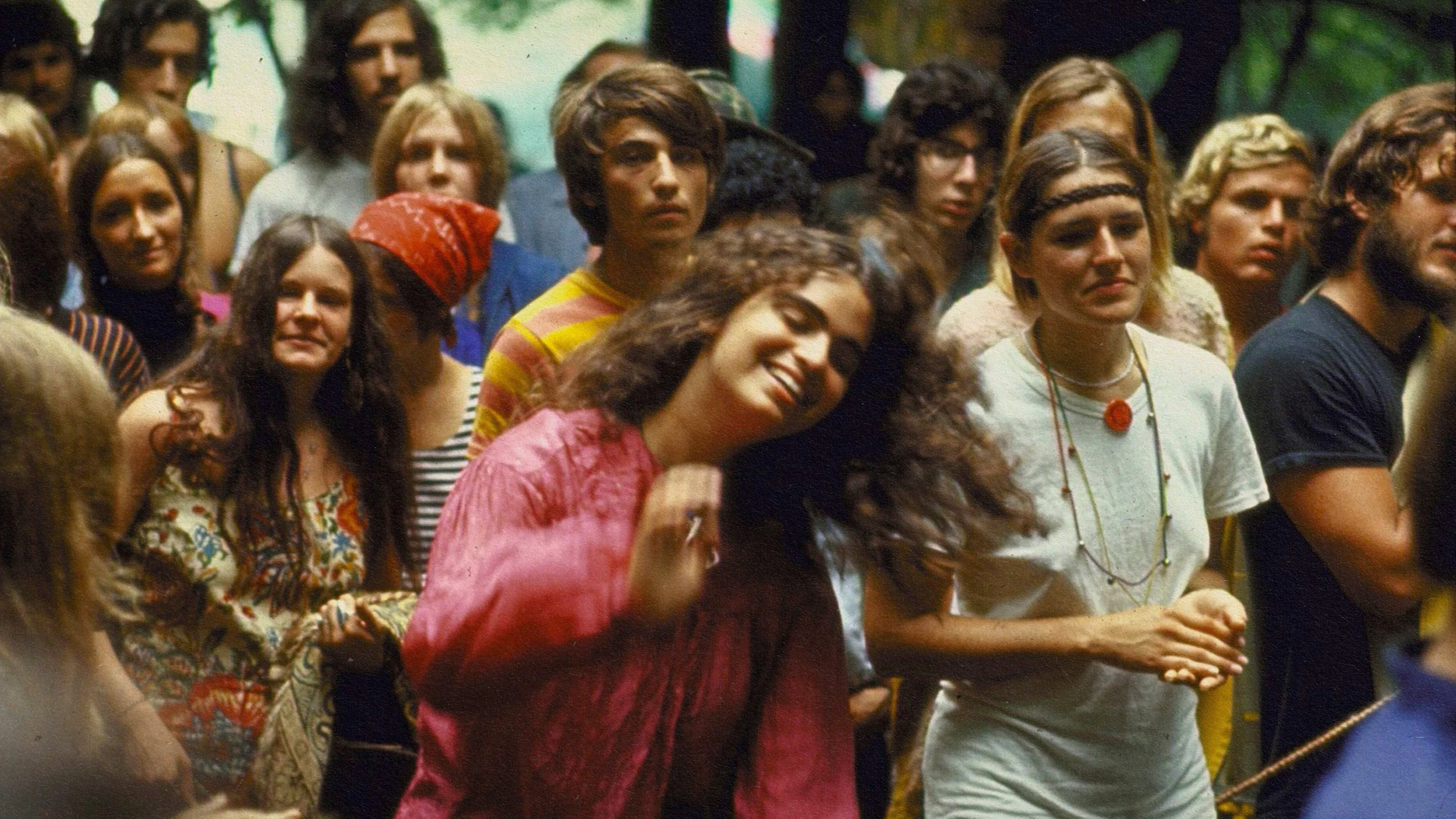

In the summer of 2017, the song suddenly took off in Indonesia when the hashtag #BabySharkChallenge got fans to making their own “Baby Shark” dance videos, complete with childishly simple hand gestures to act out the lyrics. The most popular “Baby Shark Dance” is from Pinkfong itself, and has been watched 1.6 billion times.

(Pinkfong)

All of which brings to mind two questions:

- What is it about this silly little song that makes it so mindbogglingly popular?

- How do I get the evil thing out of my head?

Two undeniable secret ingredients of a popular song

Derek Thompson, author of “Hit Makers: The Science of Popularity in an Age of Distraction,” recently spoke with Big Think about the factors that go into making a hit song. He’s given it a lot of thought, and what he says makes sense with “Baby Shark.”

Repetition: The God particle of music

Thompson spoke with musicologist at the University of California San Diego, Diana Deutsch, and she shared an epiphany she had listening to herself speak one evening at home. The insight revealed a signal difference between speech and music: Repetition. She noted that steadily repeating any short spoken phrase over and over eventually begins to sound like music.

It’s not a new idea that popular music incorporates a great deal of repetition, but the fact is that it gets to us. At its heart – it’s rhythm – and we like it. It can get us excited, and it can be as primally comforting as being rocked back and forth by a loving parent.

Certainly, “Baby Shark” has repetition in spades, with each line being so similar. There’s also that string of six repeated “doos.”

Surprise

Thompson also cites David Huron of San Diego to Ohio State University in Columbus Ohio, who has performed experiments with mice in which playing a note for a rodent subject caused it to turn its head toward the sound. The mouse would continue to do this until it essentially lost interest in the note, or became dishabituated to it. Playing a different note re-engaged the mouse, even to the extent that returning to the first note saw the mouse react to it with renewed interest. Huron experimented with different series of notes. He worked out that to keep the mouse engaged for the longest time with the fewest notes, Note 1, Note 1, Note 2, Note 1, Note 2, Note 3, repeat, will do the trick.

As Thompson notes, if one looks at the most successful popular song structures, you see a similar, refresh-the-listener stratagem at work.

One of the most enjoyable aspects of playing music is that it so captures your attention while playing, and this is true as well for listening to it. Every new thing we hear grabs our attention all over again, dishabituating us and keeping us interested. This may well be part of why music so powerfully engages us – it continually demands our attention.

Any kind of surprise can be effective: A surprising lyric, an unexpected chord change, a sound, even a mistake. One of the most popular albums of the 1990s, for example, was Alanis Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill, in which Morissette and her producer Glen Ballard wisely decided not to tidy things up too much, leaving in some pitchy vocal phrases and unexplored idea fragments. It had the effect of somehow making the music more alive so that it jumped right out of listening systems and into millions of people’s lives.

In the case of “Baby Shark,” the song keeps the kids’ attention by giving each four-line verse a different beginning, such as “baby shark, “mommy shark,” “daddy shark,” etc. This demands that kids stay alert and be ready to sing along with what comes next. There’s no habituation possible here if you want to keep up.

Is there a formula?

A while back we wrote about an experiment conducted by the C&G Baby Club and the Grammy® award-winning Imogen Heap, in which they attempted to develop a formula for composing and recording a song that babies would love. What they worked out were five requirements:

- The song needed to be in a major key.

- The song needed a simple, repetitive melody.

- The song needed to contain little surprises to delight baby and keep her/him on her/his teeny toes, including drum rolls, key changes, and upward portamenti (pitch glides).

- The song needed to be very uptempo, since babies hearts beat fast.

- The song needs to have an engaged and energetic female lead vocal, recorded in front of a baby if possible.

So, how does “Baby Shark” fare? Not bad. Four out of five:

- Check

- Check

- Check

- Check

- Nope.

Here’s the song Heap and C&G built from this recipe.

One of the great mysteries

Even with all this thought and analysis, who could’ve predicted what’s happened with “Baby Shark?” What makes one piece of music work and another fail remains mysterious, and proof that this is true can be found in the fact that very few artists can pump out hit after hit. And when they do, it doesn’t usually last long because what they do seems less and less surprising, and their fans eventually habituate to their music. Unless they keep changing. Ever wonder why each Beatles album was so different than the last?