Where in the body we feel all those feels

“Subjective feelings are a central feature of human life, yet their relative organization has remained elusive.” This is the opening sentence of a new study that sought to identify, classify, and categorize for the first time the range of human feelings. The study’s Finnish authors — Lauri Nummenmaa, Riitta Hari, Jari K. Hietanen, and Enrico Glerean — have published their conclusions in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

“Feelings,” like the word in Finnish, “tunteet,” carries arguably too wide a meaning. It encompasses a range of things, including positive and negative emotions, thought processes, physical sensations, types of discomfort, and a need to achieve some physical state, as in when you experience both a feeling of hunger and then its satisfaction. The researchers charted all of these, distilling them down to 100 “core” feelings.

The study’s methodology

The primary source of data in the study was the set of responses from 1,026 subjects who filled out online questionnaires that were divided into three parts:

- For each of the 100 feelings, they were asked to rate the feeling’s intensity, or salience, in terms of mental experience, bodily sensation, emotion, and controllability

- They were asked to subjectively identify the similarity between multiple feelings

- They were asked to identify where in their bodies they experienced each of the 100 feelings

The researchers then looked for neural similarities between feelings that participants had grouped together, using the NeuroSynth meta-analysis database. The database is culled from 9,821 brain-imaging studies.

When all of this data was collated, the authors were able to create five feeling clusters:

- positive emotions — including happiness, love, pride, relaxation, and sympathy

- negative emotions — including anger, fear, disgust, shame, and loneliness

- cognitive processes — including thinking, daydreaming, reasoning, estimating and remembering

- somatic states and illnesses — including coughing, itching, shivering, having a toothache, and pain

- homeostatic states — including hunger and thirst on one hand, and eating and drinking on the other

The lines between clusters are perhaps not always as clear as one might like, thanks again to the difficulty of categorizing feelings. For example, a feeling of orgasm is considered a positive emotion when it seems it could just as easily be deemed a somatic state. Likewise, one might argue that cognitive processes aren’t feelings at all, but actions, and that they don’t belong in a study of feelings — do we ever feel that we’re thinking?

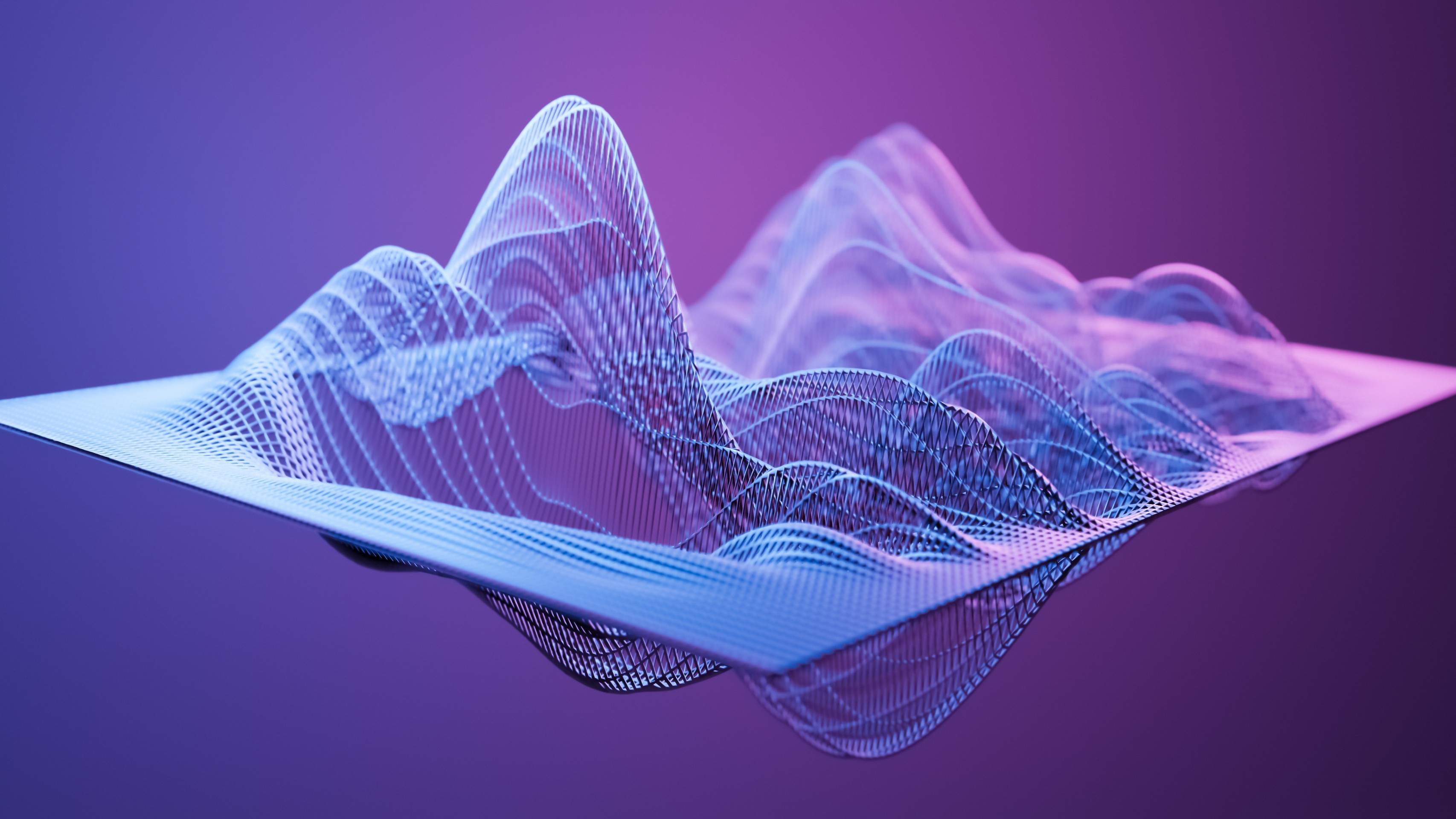

The emotional space visualized

The data allowed the authors to map the entire human feeling space, with lines interconnecting the 100 feelings according to their reported similarities. In the illustration below, the vertical axis shows the intensity of the mapped feelings, while the horizontal axis shows their valance, that is their relative positive or negative impact.

At the bottom is a heat map showing the strength of the feelings in each area of the map.

The emotional body

The researchers also were able to produce heat maps of the human body reflecting where the respondents claimed to feel each of the emotions. Some of it is obvious, as in cognitive processing being felt in the head, seeing being felt in the eyes, and some seem to correspond to cultural metaphors, as in sympathy being felt in the cardiac region. Still, it’s pretty interesting.

(IFLScience has made a video of the body heat mapping.)

Finally, the authors performed a subsequent analysis that confirmed for them a connection between the body heat maps and the feeling clusters depicted in the feeling space.

The process of making sense of our feelings is beyond tricky, especially if one includes the non-emotional varieties. Still, this is a fascinating attempt. At least that’s how we feel.