The U.S. Won’t Strike First, and Why Obama’s Struggling with Saying So

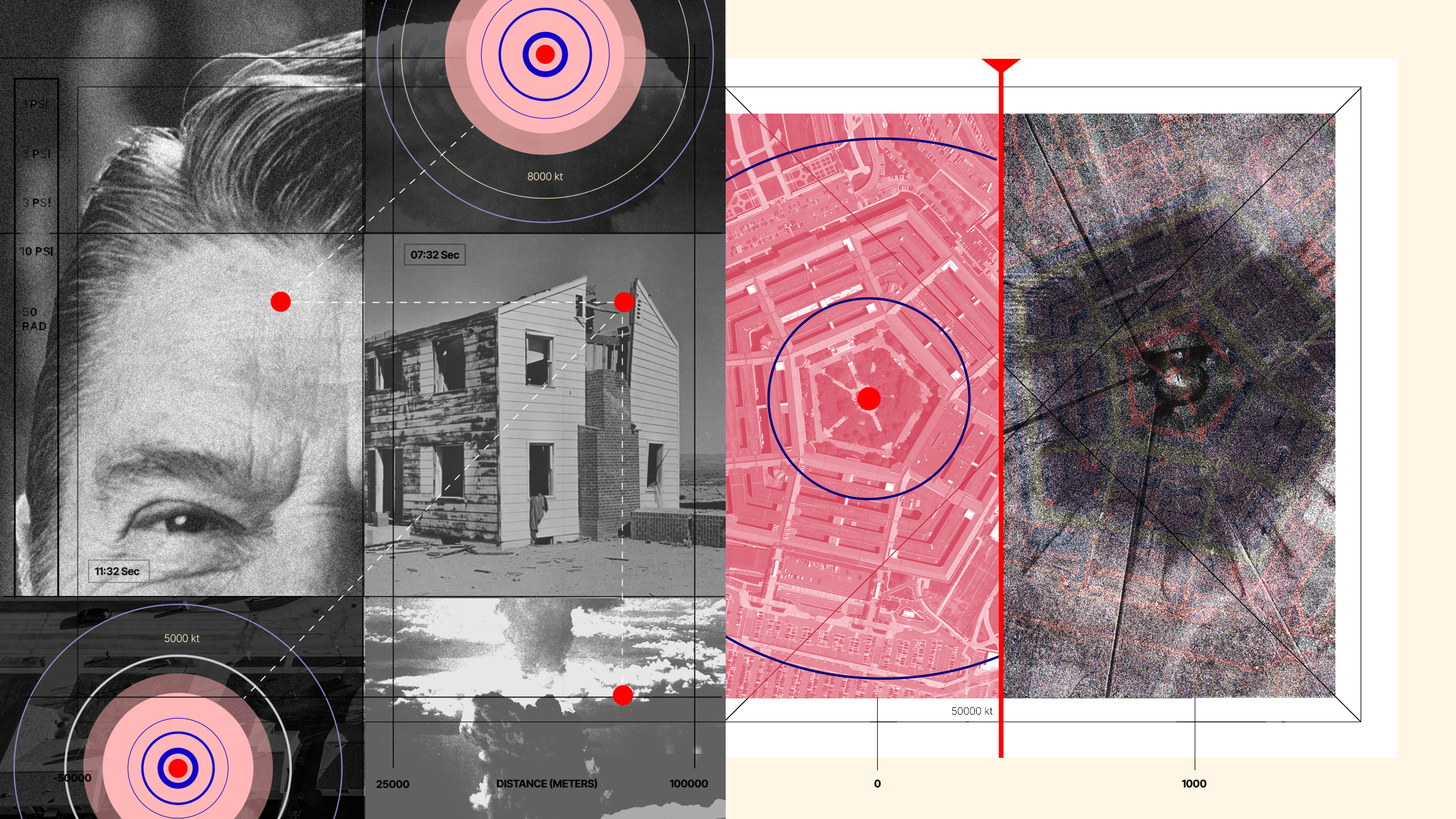

Every since we let the nuclear genie out of the bottle with the Manhattan Project, we’ve been looking for a way to stuff it back in. Almost immediately after bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II — America being the only country ever to use nuclear weapons in war — U. S. presidents have positioned their arsenal as a deterrent, letting other nuclear countries know that should they use their weapons against the U.S., America would retaliate with annihilating nuclear force. The U.S. and Soviet Union (USSR) have engaged in a long game of one-upmanship, each trying to show that its nuclear deterrent was bigger and scarier than the other guy’s. Currently, the US has 6,970 nuclear weapons and Russia 7,300. Both countries can wipe out humanity many times over.

Titan Missile (TODD LAPPIN)

At this point, though, it’s no longer a precarious balancing act between super-powers. A number of countries possess nuclear capabilities and others are in the process of developing them. Some of these countries are subject to extreme political realignments, and so control of a nuclear arsenal can change overnight. When you factor in the terror organizations with publicly stated intentions of gaining access to nuclear technology, you can practically hear the time-bomb ticking.

Advocates of arms control have been urging President Obama to take concrete steps toward global disarmament. U.S. presidents since Truman have believed that credible deterrence requires a nuclear first-strike to be viewed only as a last-resort option, though this has never been officially stated. President Obama had been considering changing this, making an unprecedented statement of good faith, and clarifying America’s commitment to deterrence. But now it looks like he’s changing his mind.

(POOL)

National security advisers, and some administration alumni, are arguing that such a statement would cause allies such as Japan and South Korea to feel newly vulnerable.

There’s undeniably concern over Russia’s and China’s recent geopolitical attitudes: Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and troop movements into the Ukraine are chillingly reminiscent of Soviet behavior, and China’s increasingly adamant claims over the South China Sea have observers fearful about their intentions.

The dynamic at play — serious as it is — is a fascinating example of the power of diplomatic communication. The U.S. policy of deterrence has always implied that the country would not strike first, so making that official would simply be a pubic recognition of what’s always been understood by all parties. The fear is, however, that a public commitment has more diplomatic weight than an unspoken understanding, and as such amounts to a type of unilateral disarmament that could lead to a perception of weakness. On top of this, the consideration, and then discarding, of the commitment to a no-first-strike policy risks pushing the conversation in the opposite direction, suggesting the U.S. does have a first-strike policy. Does this mean deterrence subtly expands from responding to other countries’ first strikes to whatever we fee like? Eek.

To say this is a delicate dance is therefore putting it mildly, and there are no doubt some who wish the idea of publicly asserting a no-first-strike policy had never come up in the first place. Right now, there doesn’t seem to a move that doesn’t, one way or another, undermine the deterrence that’s kept the world’s nuclear peace for 60 years.